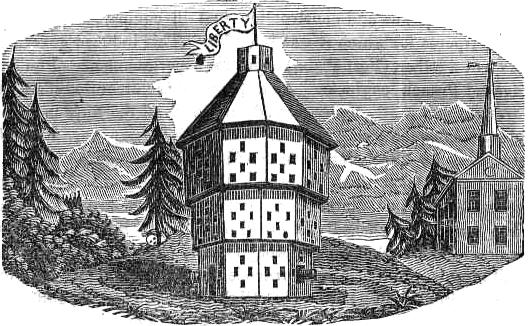

The Fort was

situated on the brow of the hill, about half a mile north-west of the village,

so as to command a full view of the valley, and the rise of the ground, for

several miles in any direction; and hence it doubtless derived its name, because,

its beautiful location commanded a "plain" view of the surrounding

country. It was erected by the government, as a fortress, and place of retreat

and safety for the inhabitants and families in case of incursions from the

Indians, who were then, and, indeed, more or less during the whole Revolutionary

war, infesting the settlements of this whole region. Its form was an octagon,

having port-holes for heavy ordonance and muskets on every side. It contained

three stories or apartments. The first story was thirty feet in diameter;

the se-

* Fort

Plank, as it is written in the books, was situated, two and a half miles from

Fort Plain. The true name was Fort Blank, from the name of the owner of the

farm on which it stood-Frederick Blank.

cond, forty feet;

the third, fifty feet; the last two stories projecting five feet, as represented

by the drawing aforesaid. It was constructed throughout of hewn timber about

fifteen inches square; and, beside the port-holes aforesaid, the second and

third stories had perpendicular port-holes through those parts that projected,

so as to afford the regulars and militia, or settlers garrisoned in the fort,

annoying facilities of defence for themselves, wives, and children, in case

of close assault from the relentless savage. Whenever scouts came in with

tidings that a hostile party was approaching, a cannon was fired from the

fort as a signal to flee to it for safety. In the early part of the war there

was built, by the inhabitants probably, at or near the site of the one above

described, a fortification, of materials and construction that ill comported

with the use and purposes for which it was intended. This induced government

to erect another, (Fort Plain,) under the superintendence of an experienced

French engineer. As a piece of architecture, it was well wrought and neatly

finished, and surpassed all the forts in that region. After the termination

of the Revolutionary war, Fort Plain was used for some years as a deposit

of military stores, under the direction of Captain B. Hudson. These stores

were finally ordered by the United States Government to be removed to Albany.

The fort is demolished. Nothing remains of it except a circumvallation or

trench, which, although nearly obliterated by the plough, still indicates

to the curious traveller sufficient evidence of a fortification in days by-gone.-

Fort Plain Journal, Dec. 26,1837.

No. II.

[REFERENCE FROM

PAGE 153.]

Copy of another paper in the same hand-writing, taken with the letter to General

Haldimand from Dr. Smith.

"April 20,1781.

" FORT STANWIX.

" THIS post is garrisoned by about two hundred and sixty men, under the

command of Colonel Courtlandt. It was supplied with provision about the 14th

of last month, and Brant was too early to hit their sleys ; he was there on

the 2d ; took sixteen prisoners. A nine-inch mortar is ordered from Albany

to this fort, to be supplied against the latter end of May; The nine months'

men raised are to join Courtlandt's.

" 25th May.--Fort

Stanwix is entirely consumed by fire, except two small bastions ; some say

by accident, but it is generally thought the soldiers done it on purpose,

as their allowance is short; provision stopped from going there, which was

on its way.

JOHN'S TOWN.

" At this

place there is a captain's guard.

" MOHAWK

RIVER.

" There

are no troops, or warlike preparations (as yet) making in this quarter; but

it is reported, that as soon as the three years and nine months' men are raised,

they will erect fortifications. From this place and its vicinage many families

have moved this winter, and it is thought more will follow the example this

spring.

" SCHENECTADY.

" This town

is strongly picketed all round ; has six pieces of ordnance, six pounders,

block-houses preparing. It is to be defended by the inhabitants ; (except

about a dozen) are for Government. There are a few of Courtlandt's regiment

here; a large quantity of grain stored here for the use of the troops ; large

boats building to convey heavy metal and shot to Fort Stanwix.

" ALBANY.

" No troops at this post, except the Commandant, General Clinton, and

his Brigade Major. Work of all kinds stopped for want of provisions and money.

The sick in the hospitals, and their doctors, starving. 8th May-No troops

yet in this place ; a fine time to bring it to submission, and carry off a

tribe of incendiaries.

" WASHINGTON'S

CAMP.

" The strength of this camp does not exceed twenty-five thousand. Provisions

of all kinds very scarce. Washington and the French have agents through the

country, buying wheat and flour. He has sent to Albany for all the cannon,

quick-match, &c., that was deposited there. Desertions daily from the

different posts. The flower of the army gone to the southward with the Marquis

De Lafayette.

" May 8th.

They say Washington is collecting troops fast.

" SOUTHERN

NEWS.

" On the 15th of March, Lord Cornwallis attacked General Green at Guilford

Court House, in North Carolina, and defeated him with the loss on Green's

side of thirteen hundred men killed, wounded, and missing ; his artillery,

and two ammunition wagons taken, and Generals Starns and Hegu wounded.

" May 20th.

Something very particular happened lately between here and New-York, much

in the King's favor, but the particulars, kept a secret.

" The inhabitants

between Albany and Boston, and several precincts, drink the King's health

publicly, and seem enchanted with the late proclamation from New-York. By

a person ten days ago from Rhode Island, we have an accounts that the number

of land forces belonging to the French does not amount to more than three

hundred ; that when he left it, he saw two of the French vessels from Chesapeake

much damaged and towed in; that several boats full of wounded were brought

and put into their hospitals, and that only three vessels out of the eight

which left the island escaped, the remainder brought into York. Out eastward

of Boston is acting on the Vermont principle.

" STATE

OF VERMONT.

" The opinion of the people in general of this State is, that its inhabitants

are artful and cunning, full of thrift and design. About fifteen days ago

Colonel Allen and a Mr. Fay was in Albany. I made it my particular business

to be twice in their company ; at which time I endeavored to find out their

business, and on inquiry I understood from Colonel Allen that he came down

to wait on Govenor Clinton, to receive his answer to a petition which the

people of Vermont had laid before the Assembly ; that he had been twice at

the Governor's lodging, and that the Governor had refused to see or speak

to him. Allen then said he might be damned if ever he would court his favor

again: since that time they have petitioned the Eastern States to be in their

Confederacy, to no purpose. I heard Allen declare to one Harper that there

was a North Pole and a South Pole; and should a thunder-gust come from the

south, they would shut the door opposite to that point and open the door facing

the north.

" 8th May.

By this time it is expected they will be friendly to their King ; various

opinions about their flag.

" SARATOGA.

" At this post there is a company belonging to Van Schaick's regiment,

lately come from Fort Edward; which garrison they left for want of provision;

and here they are determined not to stay for the same reason. A fort erecting

here by General Schuyler. Two hundred and fifty men at this place.

"FORT EDWARD.

"Evacuated. Now is the time to strike a blow in these parts. A party

toward Johnstown, by way of Division, and a considerable body down here, will

effect your wish.

GENERAL INTELLIGENCE.

" Norman's Kill, Nisquitha, Hillbarrack, and New Scotland, will immediately

on the arrival of his Majesty's troops, join and give provision. Several townships

east of Albany and south-east, are ready to do the like. Governor Trumbull's

son was hanged in London for a spy: he had several letters from Dr. Franklin

to some lords, which were found upon him.* No mention in the last Fishkill

papers that Greene obliged his Lordship to retreat, as has been reported.

The Cork fleet, of upward of one hundred sail, are safely arrived in York.

No hostile intentions on foot against the Province of Canada.

" May 25.

I just received a line from T. H. but before his arrival, I despatched a courier

on the point of a sharp weapon, to which I refer you ; and lest that should

miscarry, I send you my journal, from which, and the extract sent forward,

you may, if it arrives, form something interesting. For God's sake, send a

flag for me. My life is miserable. I have fair promises, but delays are dangerous."

With the above

was taken another paper in the same hand-writing, of which the following is

a copy :

" Y. H.

is disobedient, and neither regards or pays any respect to his parents : if

he did, he would contribute to their disquiet, by coming down contrary to

their approbation and repeated requests. "

" The necessaries

you require are gone forward last Tuesday by a person which the bearer will

inform you of. I wish he was in your company, and you all safely returned,

&c.

" My life

is miserable. A flag-a flag, and that immediately, is the sincere wish of

"H. SENIOR."

*

The reference here is to Colonel John Trumbull, the former Adjutant General

of the northern department, who, so far from having been hanged at the time

mentioned, is yet living, (Feb. 1838,) having served his country faithfully

and successfully in a high civil capacity since the war of the Revolution,

but, more to its glory still, by his contributions to the arts. It is true,

that at the time referred to by the writer of these memoranda, Colonel Trumbull

was in London. He had repaired thither to study the divine art which he has

so long and successfully cultivated, under the

instruction of his countryman, West, and with the tacit permission of the

British ministers. Owing, however, to the intrigues of some of the American

loyalists in London, who hated him bitterly, he was arrested in London during

the Autumn of 1780, on a charge of treason, and committed to the common prison.

He had a narrow escape, especially as great exasperation was kindled by the

execution of Andre, and it was hoped that an offset might be made in the person

of the son of a rebel Governor. West interceded with the King, and Trumbull

was liberated. Colonel Trumbull's Memoirs, which are in course of preparation,

will contain an interesting account of this affair, which was most disgraceful

to those who compassed his arrest.-Author.

No. III.

[REFERENCE FROM PAGE 165.]

1.

A FIRM fortress is our God, a good defence and weapon; He helps us free from

all our troubles which have now befallen us. The old evil enemy, he is now

seriously going to work; Great power and much cunning are his cruel equipments,

There is none like him on the earth.

2.

With our own strength nothing can be done, we are very soon lost: For us the

right man is fighting, whom God himself has chosen. Do you ask, who he is

? His name is Jesus Christ, The Lord Jehovah, and there is no other God ;

He must hold the field.

3.

And if the world were full of devils, ready to devour us, We are by no means

much afraid, for finally we must overcome The prince of this world, however

badly he may behave, He cannot injure us, and the reason is, because he is

judge ; A little word can lay him low.

4.

That word they shall suffer to remain, and not to be thanked for either: He

is with us in the field, with his Spirit and his gifts. If they take from

us body, property, honor, child and wife, Let them all be taken away, they

have yet no gain from it, The kingdom of heaven must remain to us.

[The above is

from a hymn book A. D. 1741. In one printed in 1826, and now in use in Pennsylvania,

the following is added:]

5.

Praise, honor and glory to the Highest God, the Father of all Mercy. Who has

given us out of love His Son, for the sake of our defects, Together with the

Holy Spirit. He calls us to the Kingdom : He takes away from us our sins,

and shows us the way to heaven ; May He joyfully aid us. Amen.

No. IV.

[REFERENCE FROM PAGE 167.]

Colonel Gansevoort's Address to the late 3d New- York Regiment. [Regimental

Orders.]

" Saratoga,

Dec. 30th, 1780.

"THE Colonel being by the new arrangement necessitated to quit the command

of his regiment, and intending to leave this post on the morrow, returns his

sincerest thanks to the officers and soldiers whom he has had the honor to

command, for the alacrity, cheerfulness, and zeal, which it affords him peculiar

satisfaction to declare they have so frequently evinced in the execution of

those duties which their stations required them to discharge, and for their

attention to his orders, which, as it ever merited, always had his warmest

approbation.

" Though

he confesses that it is with some degree of pain he reflects that the relation

in which they stood is dissolved, he will endeavor to submit without repining

to a circumstance which, though it may have a tendency to wound his feelings,

his fellow-citizens who form the councils of the states have declared would

be promotive of the public weal.

" In whatever

situation of life he may be placed, he will always with pleasure cherish the

remembrance of those deserving men who have with him been sharers of almost

every hardship incident to a military life. As he will now probably return

to that class of citizens whence his country's service at an early period

of the war drew him, he cordially wishes the day may not be very remote when

a happy peace will put them in the full enjoyment of those blessings for the

attainment of which they have nobly endured every inconvenience and braved

many dangers.

"P. GANSEVOORT."

An Address

to Colonel Peter Gansevoort, by the Officers of his Regiment, on his retiring

from service, in consequence of the new arrangement ordered by Congress.

" Saratoga,

Dec. 31, 1780.

" Sir,

" Permit us, who are now with reluctance separated from your command,

and deprived of the benefits which we frequently experienced therefrom, to

declare our sentiments with a warmth of affection and gratitude, inspired

by a consciousness of your unwearied attention to the welfare, honor, and

prosperity of the Third New York Regiment, while it was honored by your command.

" We should

have been peculiarly happy in your continuance with us. From our long experience

of your invariable attachment to the service of our country, your known and

approved abilities, and that affable and gentlemanlike deportment by which

(permit us to say) you have so endeared yourself to officers and soldiers,

that we cannot but consider the separation as a great misfortune.

" Although

your return to the class of citizens from whence our country's cause, at an

early period, called you, it is not a matter of choice in you, nor by any

means agreeable to us; yet it cannot but be pleasing to know that you retire

with the sincerest affection, and most cordial esteem and regards of the officers

and men you have commanded.

" We are,

with the utmost respect,

" Sir,

" Your most humble servants,

JAS. ROSEKRANS,

Major,

CORN'S. T. GANSEN, Captain,

J. GREGG, do,

LEONARD BLEEKER, do.

GEO. SYTEZ, do.

HENRY TIEBOUT, do,

HUNLOKE WOODRUFF, Surgeon,

J. VAN RENSSELAER, Paymaster,

DOUW T. FONDAY, Ensign,

B. BOGAEDUS, Lieutenant,

J. BAGLEY, do.

CHRS. HATTON, do.

W. MAGEE, do.

PRENTICE BOWEN, do.

SAML. LEWIS, do.

JOHN ELLIOT, Surgeon's Mate,

BENNJ. HERRING, Ensign,

GERRIT LANSING, do.

[REFERENCE FROM

PAGE 236.]

At a meeting of the principal inhabitants of the Mohawk District, in Tryon

County, Colonel JOSEPH THROOP in the Chair,

TAKING into consideration

the peculiar circumstances of this country, relating to its situation, and

the numbers that joined the enemy from among us, whose brutal barbarities

in their frequent visits to their old neighbours, are shocking to humanity

to relate :

They have murdered

the peaceful husbandman and his lovely boys about him, unarmed and defenceless

in the field. They have, with a malicious pleasure, butchered the aged and

inform ; they have wantonly sported with the lives of helpless women and children

; numbers they have scalped alive, shut them up in their houses, and burnt

them to death. Several children, by the vigilance of their friends, have been

snatched from flaming buildings; and, though tomahawked and scalped; are still

living among us; they have made more than three hundred widows, and above

two thousand orphans in this county ; they have killed thousands of cattle

and horses that rotted in the field ; they have burnt more than two millions

of bushels of grain, many hundreds of buildings, and vast stores of forage;

and now these merciless fiends are creeping in among us again, to claim the

privilege of fellow, citizens and demand a restitution of their forfeited

estates; but can they leave their infernal tempers behind them, and be safe

or peaceable neighbors ? Or can the disconsolate widow and the bereaved mother

reconcile her tender feelings to a free and cheerful neighborhood with those

who so inhumanly made her such ? Impossible! It is contrary to nature, the

first principle of which is self-preservation; it is contrary to the law of

nations, especially that nation, which, for numberless reasons, we should

be thought to pattern after. Since the accession of the House of Hanover to

the British throne, five hundred and twenty peerages in Scotland have been

sunk, the Peers executed or fled, and their estates confiscated to the crown,

for adhering to their former administration after a, new one was established

by law. It is contrary to the eternal rule of reason and rectitude. If Britain

employed them, let Britain pay them ! We will not.

Therefore, Resolved

unanimously, that all those who have gone off to the enemy, or have been banished

by any law of this state, or those who we shall find tarried as spies or tools

of the enemy, and encouraged and harbored those who went away, shall not live

in this district on any pretence whatever; and as for those who have washed

their faces from Indian paint, and their hands from the innocent blood of

our dear ones, and have returned either openly or covertly, we hereby warn

them to leave this district before the twentieth of June nest, or they may

expect to feel the just resentment of an injured and determined people.

We likewise unanimously

desire our brethren in the other districts in this county to join with us,

to instruct our representatives not to consent to the repealing any laws made

for the safety of the state, against treason or confiscation of traitors'

estates; or to passing any new acts for the return or restitution of Tories.

By order of the Meeting,

May 9, 1783. JOSIAH THROOP, Chairman.

At a meeting

of the freeholders and inhabitants of Canajoharie District, in the County

of Tryon, held at Fort Plain in the same district, on Saturday the 7th day

of June, 1783, the following resolves were unanimously entered into. Lieutenant

Colonel Samuel Clyde in the Chair :

Whereas,

In the course of the late war, large numbers of the inhabitants of this county,

lost to every sense of the duty they owed their country, have joined the enemies

of this state, and have, in conjunction with the British troops, waged war

on the people of this state; while others, more abandoned, have remained among

us, and have harbored, aided, assisted, and victualled the said British troops

and their adherents; and by their example and influence have encouraged many

to desert the service of their country, and by insults and threats have discouraged

the virtuous citizens, thereby inducing a number to abandon their estates

and the defence of their country: and whereas, the County of Tryon hath, in

an especial manner, been exposed to the continued inroads and incursions of

the enemy, in which inroads and incursions the most cruel murders, robberies,

and depredations have been committed that ever yet happened in this or any

other country ; neither sex nor age being spared, insomuch that the most aged

people of each sex, and infants at their mothers' breasts, have inhumanly

been butchered ; our buildings (the edifices dedicated to the service of Almighty

God not excepted) have been reduced to ashes; our property destroyed and carried

away; our people carried through a far and distant wilderness, into captivity

among savages (the dear and faithful allies of the merciful and humane British!)

where very many still remain, and have by ill usage been forced to enter into

their service.

And whereas,

Through the blessings of God and the smiles of indulgent Providence, the war

has happily terminated, and the freedom and independence of the United States

firmly established :

And whereas,

It is contrary to the interests of this county, as well as contrary to the

dictates of reason, that those persons who have, through the course of an

eight years' cruel war, been continually aiding and assisting the British

to destroy the liberties and freedom of America, should now be permitted to

return to, or remain in this county, and enjoy the blessings of those free

governments established at the expense of our blood and treasure, and which

they, by every unwarrantable means, have been constantly laboring to destroy,

Resolved,

That we will not suffer or permit any person or persons whatever, who have

during the course of the late war joined the enemy of this state, or such

person or persons remaining with is, and who have any ways aided, assisted,

victualled, or harbored the enemy, or such as have corresponded with them,

to return to, or remain in this district.

Resolved,

That all other persons of disaffected or equivocal character, who have by

their examples, insults, and threatenings, occasioned any desertions to the

enemy, or have induced any of the virtuous citizens of this county to abandon

their habitations, whereby they were brought to poverty and distress. And

all such as during the late war have been deemed dangerous, shall not be permitted

to continue in this district, or to return to it.

Resolved,

That all such persons now remaining in this district, and comprehended in

either of the above resolutions, shall depart the same within one month after

the publication of this.

Resolved,

That no person or persons, of any denominations whatever, shall be suffered

to come and reside in this district, unless such person or persons shall bring

with them sufficient vouchers of their moral characters, and of their full,

entire, and unequivocal attachment to the freedom and independence of the

United States.

Resolved,

That we will, and hereby do associate, under all the ties held sacred among

men and Christians, to stand to, abide by, and carry into full effect and

execution, all and every the foregoing resolutions.

Resolved,

That this district does hereby instruct the members in Senate and Assembly

of this state from this county, to the utmost of their power to oppose the

return of all such person or persons who are comprehended within the sense

and meaning of the above resolutions.

Ordered,

That the preceding votes and proceedings of this district be signed by the

Chairman, and published in the New York Gazetteer.

SAMUEL CLYDE, Chairman.

No. VI.

[REFERENCE FROM PAGE 288.]

" AT a meeting

of the President and Fellows of Harvard College, June 5th, 1789.

" Voted,

That the thanks of this Corporation be presented to Colonel Joseph Brant,

Chief of the Mohawk Nation, for his polite attention to this University, in

his kind donation to its library of the Book of Common Prayer of the Church

of England, with the Gospel of Mark, translated into the Mohawk language,

and a Primer in the same language.

" Attest,

JOSEPH WILLARD, President"

[REFERENCE FROM PAGE 312.]

SAINCLAIRE'S DEFEAT.

'Twas November the fourth, in year of ninety-one, We had a

sore engagement near to Fort Jefferson; Sinclaire was our commander, which

may remembered be, For there we left nine hundred men in t' West'n Ter'tory.

At Bunker's

Hill and Quebec, where many a hero fell, Likewise at Long Island, (it is I

the truth can tell,) But such a dreadful carnage may I never see again As

hap'ned near St. Mary's upon the river plain.

Our army was

attacked just as the day did dawn, And soon were overpowered and driven from

the lawn; They killed Major Ouldham, Levin, and Briggs likewise, And horrid

yell of savages resounded thro' the skies.

Major Butler

was wounded the very second fire; His manly bosom swell'd with rage when forc'd

to retire; And as he lay in anguish, nor scarcely could he see, Exclaimed,

" Ye hounds of hell, O! revenged I will be."

We had not been

long broken when General Butler found Himself so badly wounded, was forced

to quit the ground: " My God!" says he, " what shall we do

; we're wounded every man Go, charge them, valiant heroes, and beat them,

if you can."

He leaned his

back against a tree, and there resigned his breath, And like a valiant soldier

sunk in the arms of death; When blessed angels did await, his spirit to convey;

And unto the celestial fields he quickly bent his way.

We charg'd again

with courage firm, but soon again gave ground, The war-whoop then re-doubled,

as did the foes around; They killed Major Ferguson, which caused his men to

cry, " Our only safety is in flight, or fighting here to die."

Stand to your

guns," says valiant Ford, " let's die upon them there, Before we

let the sav'ges know we ever habored fear.'' Our cannon balls exhausted, and

artillery-men all slain, Obliged were our musket-men the en'my to sustain.

Yet three hours

more we fought them, and then were forc'd to yield, When three hundred bloody

warriors lay stretched upon the field. Says Colonel Gibson to his men, "

My boys, be not dismayed, ' I'm sure that true Virginians were never yet afraid.

"Ten thousand

deaths I'd rather die, than they should gain the field:" With that he

got a fatal shot, which caused him to yield. Says Major Clark, " My heroes,

I can here no longer stand, We'll strive to form in order, and retreat the

best we can."

The word 'Retreat'

being past around, there was a dismal cry Then helter-skelter through the

woods, like wolves and sheep they fly; This well-appointed army, who, but

a day before, Defied and braved all danger, had like a cloud pass'd o'er.

Alas! the dying

and wounded, how dreadful was the thought, To the tomahawk and scalping-knife,

in mis'ry are brought; Some had a thigh and some an arm broke on the field

that day, Who writhed in torments at the stake, to close the dire affray

To mention our

brave officers is what I wish to do; No sons of Mars e'er fought more brave,

or with more courage true. To Captain Bradford I belonged, in his artillery

; He fell that day amongst the slain, a valiant man was he.

No. VIII.

[REFERENCE FROM PAGE 314.]

Narrative of the Captivity and Sufferings of Massy Harbison, in the Spring

of 1792, who resided in the neighborhood of Pittsburgh, together with the

Murder of her children, her own escape, &c.

ON the return

of my husband from General St. Clair's defeat, mentioned in a preceding chapter,

and on his recovery from the wound he received in the battle, he was made

a spy, and ordered to the woods on duty, about the 28d of March, 1792. The

appointment of spies vol. II.

to watch the

movements of the savages was so consonant with the desires and interests of

the inhabitants, that the frontier now resumed the appearance of quiet and

confidence. Those who had for nearly a year been huddled together in the block-house

were scattered to their own habitations, and began the cultivation of their

farms. The spies saw nothing to alarm them, or to induce them to apprehend

danger, till the fatal morning of my captivity. They repeatedly came to our

house, to receive refreshments and to lodge.

On the 15th of

May, my husband, with Captain Giithrie and other spies, came home about dark,

and wanted supper ; to procure which I requested one of the spies to accompany

me to the spring and spring-house, and Mr. William Maxwell complied with my

request. While he was at the spring and spring-house, we both distinctly heard

a sound like the bleating of a lamb or fawn. This greatly alarmed us, and

induced us to make a hasty retreat into the house. Whether this was an Indian

decoy, or a warning of what I was to pass through, I am unable to determine.

But from this time and circumstance, I became considerably alarmed, and entreated

my husband to remove me to some more secure place from Indian cruelties. But

Providence had designed that I should become a victim to their rage, and that

mercy should be made manifest in my deliverance.

On the night

of the 21st of May, two of the spies, Mr. John Davis and Mr. Sutton, came

to lodge at our house, and on the morning of the 22d, at day-break, when the

horn blew at the block-house, which was within sight of our house, and distant

about two hundred yards, the two men got up and went out. I was also awake,

and saw the door open, and thought, when I was taken prisoner, that the scouts

had left it open. I intended to rise immediately ; but having a child at the

breast, and it being awakened, I lay with it at the breast to get it to sleep

again, and accidently fell asleep myself.

The spies have

since informed me that they returned to the house again, and found that I

was sleeping ; that they softly fastened the door, and went immediately to

the block-house ; and those who examined the house after the scene was over,

say both doors had the appearance of being broken open.

The first thing

I knew from falling asleep, was the Indians pulling me out of the bed by my

feet. I then looked up, and saw the house full of Indians, every one having

his gun in his left hand and tomahawk in his right. Beholding the dangerous

situation in which I was, I immediately jumped to the floor on my feet, with

the young child in my arms. I then took a petticoat to put on, having only

the one in which I slept; but the Indians took it from me, and as many as

I attempted to put on they succeeded in taking from me, so that I had to go

just as I had been in bed. While I was struggling with spine of the savages

for clothing, others of them went and took the two children out of another

bed, and immediately took the two feather beds to the door and emptied them.

The savages immediately began their work of plunder and devastation. What

they were unable to carry with them, they destroyed. While they were at their

work I made to the door, and succeeded in getting out, with one child in my

arms and another by my side ; but the other little boy was so much displeased

by being so early disturbed in the morning, that he would not come to the

door.

When I got out,

I saw Mr. Wolf, one of the soldiers, going to the spring for water, and beheld

two or three of the savages attempting to get between him and the block-house

; but Mr. Wolf was unconscious of his danger, for the savages had not yet

been discovered. I then gave a terrific scream, by which means Mr. Wolf discovered

his danger, and started to run for the block-house : seven or eight Indians

fired at him; but the only injury he received was a bullet in his arm, which

broke it. He succeeded in making his escape to the block-house. When I raised

the alarm, one of the Indians came up to me with his tomahawk, as though about

to take my life ; a second canoe and placed his hand before my mouth, and

told me to hush, when a third came with a lifted tomahawk, and attempted to

give me a blow; but the first that came raised his tomahawk and averted the

blow, and claimed me as his squaw.

The Commissary,

with his waiter, slept in the store-house near the block-house ; and upon

hearing the report of the guns, came to the door to see what was the matter,

and beholding the danger he was in made his escape to the block-house, but

not without being discovered by the Indians, several of whom fired at him,

and one of the bullets went through his handkerchief, which was tied about

his head, and took off some of his hair. The handkerchief, with several bullet

holes in it, he afterward gave to me.

The waiter, on

coming to the door, was met by the Indians, who fired upon him, and he received

two bullets through the body and fell dead by the door. The savages then set

up one of their tremendous and terrifying yells, and pushed forward, and attempted

to scalp the man they had killed ; but they were prevented from executing

their diabolical purpose by the heavy fire which was kept up through the port-holes

from the block-house.

In this scene

of horror and alarm I began to meditate an escape, and for that purpose I

attempted to direct the attention of the Indians from me, and to fix it on

the block-house; and thought if I could succeed in this, I would retreat to

a subterranean rock with which I was acquainted, which was in the run near

where we were. For this purpose I began to converse with some of those who

were near me respecting the strength of the block-house, the number of men

in it, &c., and being informed that there were forty men there, and that

they were excellent marksmen, they immediately came to the determination to

retreat, and for this purpose they ran to those who were besieging the block-house,

and brought them away. They then began to flog me with their wiping sticks,

and to order me along. Thus what I intended as the means of my escape, was

the means of accelerating my departure in the hands of the savages. But it

was no doubt ordered by a kind Providence, for the preservation of the fort

and the inhabitants in it; for when the savages gave up the attack and retreated,

some of the men in the house had the last load of ammunition in their guns,

and there was no possibility of procuring any more, for it wag all fastened

up in the store-house, which was inaccessible.

The Indians,

when they had flogged me away along with them, took my oldest boy, a lad about

five years of age, along with them, for he was still at the door by my side.

My middle little boy, who was about three years of age, had by this time obtained

a situation by the fire in the house, and was crying bitterly to me not to

go, and making bitter complaints of the depredations of the savages.

But these monsters

were not willing to let the child remain behind them: they took him by the

hand to drag him along with them, but he was so very unwilling to go, and

made such a noise by crying, that they took him up by the feet and dashed

his brains out against the threshold of the door. They then scalped and stabbed

him, and left him for dead. When I witnessed this inhuman butchery of my own

child, I gave a most indescribable and terrific scream, and felt a dimness

come over my eyes next to blindness, and my senses were nearly gone. The savages

then gave me a blow across my head and face, and brought me to my sight and

recollection again. During the whole of this agonizing scene I kept my infant

in my arms. As soon as their murder was effected, they marched me along to

the top of the bank, about forty-or sixty rods, and there they stopped and

divided the plunder which they had taken from our house; and here I counted

their number, and found them to be thirty-two, two of whom were white men

painted as Indians.

Several of the

Indians could speak English well. I knew several of them well, having seen

them go up and down the Alleghany river. I knew two of them to be from the

Seneca tribe of Indians, and two of them Munsees ; for they had called at

the shop to get their guns repaired, and I saw them there.

We went from

this place about forty rods, and they then caught Say uncle, John Carrie's

horses, and two of them, into whose custody I was put, started with me on

the horses, toward the mouth of the Kiskiminetas, and the rest of them went

off toward Puckety. When they came to the bank that descended toward the Alleghany,

the bank was so very steep, and there appeared so much danger in descending

it on horseback, that I threw myself off the horse in opposition to the will

and command of the savages.

My horse descended

without falling, but the one on which the Indian rode who had my little boy,

in descending, fell, and rolled over repeatedly; and my little boy fell back

over the horse, but was not materially injured. He was taken up by one of

the Indians, and we got to the bank of the river, where they had secreted

some bark canoes under the rocks, opposite to the island that lies between

the Kiskiminetas and Buffalo. They attempted in vain to make the horses take

the river. After trying some time to effect this, they left the horses behind

them, and took us in one of the canoes to the point of the island, and there

they left the canoe.

Here I beheld

another hard scene, for as soon as we landed, my little boy, who was still

mourning and lamenting about his little brother, and who complained that he

was injured by the fall in descending the bank, was murdered.

One of the Indians

ordered me along, probably that I should not see the horrid deed about to

be perpetrated. The other then took his tomahawk from his side, and with this

instrument of death killed and scalped him. When I beheld this second scene

of inhuman butchery, I fell to the ground senseless, with my infant in my

arms it being under, and its little hands in the hair of my head. How long

I remained in this state of insensibility, I know not.

The first thing

I remember was my raising my head from the ground, and my feeling myself exceedingly

overcome with sleep. I cast my eyes around, and saw the scalp of my dear little

boy, fresh bleeding from his head, in the hand of one of the savages, and

sunk down to the earth again upon my infant child. The first thing I remember

after witnessing this spectacle of woe, was the severe blows I was receiving

from the hands of the savages, though at that time I was unconscious of the

injury I was sustaining. After a severe castigation, they assisted me in getting

up, and supported me when up.

Here I cannot

help contemplating the peculiar interposition of Divine Providence in my behalf.

How easily might they have murdered me ! What a wonder their cruelty did not

lead them to effect it! But, instead of this, the scalp of my boy was hid

from my view and, in order to bring me to my senses again, they took me back

to the river and led me in knee deep ; this had its intended effect. But "

the tender mercies of the wicked are cruel."

We now proceeded

on our journey by crossing the island, and coming to a shallow place where

we could wade out, and so arrive to the Indian side of the country. Here they

pushed me in the river before them, and had to conduct me through it. The

water was up to my breast, but I suspended my child above the water, and,

through the assistance of the savages, got safely out.

From thence we

rapidly proceeded forward, and came to Big Buffalo ; here, the stream was

very rapid, and the Indians had again to assist me. When we had crossed this

creek, we made a straight course to the Connoquenessing creek, the very place

where Butler now stands; and from thence we travelled five or six miles to

Little Buffalo, and crossed it at the very place where Mr. B. Sarver's mill

now stands, and ascended the hill.

I now felt weary

of my life, and had a full determination to make the savages kill me, thinking

that death would be exceedingly welcome when compared with the fatigue, cruelties,

and miseries I had the prospect of enduring. To have my purpose effected,

I stood still, one of the savages being before me and the other walking on

behind me, and I took from off my shoulder a large powder horn they made me

carry, in addition to my child, who was one year and four days old. I threw

the horn on the ground, closed my eyes, and expected every moment to feel

the deadly tomahawk. But to my surprise the Indians took it up, cursed me

bitterly, and put it on my shoulder again. I took it off the second time,

and threw it on the ground, and again closed my eyes with the assurance that

I should meet death ; but, instead of this, the savages again took up the

horn, and with an indignant, frightful countenance, came and placed it on

again. I took it off the third time, and was determined to effect it; and

therefore threw it as far as I was able from me, over the rocks. The savage

immediately went after it, while the one who had claimed me as his squaw,

and who had stood and witnessed the transaction, came up to me, and said,

" well done, I did right, and was " a good squaw, and that the other

was a lazy son of a b-h ; he might "carry it himself." I cannot

now sufficiently admire the indulgent care of a gracious God, that at this

moment preserved me amidst so many temptations from the tomahawk and scalping

knife.

The savages now

changed their position, and the one who claimed me as his squaw went behind.

This movement, I believe, was to prevent the other from doing me any injury

; and we went on till we struck the Connequenessing at the Salt Lick, about

two miles above Butler, where was an Indian camp, where we arrived a little

before dark, having no refreshment during the day.

The camp was

made of stakes driven in the ground sloping, arid covered with chesnut bark,

and appeared sufficiently long for fifty men. The camp appeared to have been

occupied for some time; it was very much beaten, and large beaten paths went

out from it in different directions.

That night they

took me about three hundred yards from the camp, up a run, into a large dark

bottom, where they cut the brush in a thicket, and placed a blanket on the

ground, and permitted me to sit down with my child. They then pinioned my

arms back, only with a little liberty, so that it was with difficulty that

I managed my child. Here, in this dreary situation, without fire or refreshment,

having an infant to take care of and my arms bound behind me, and having a

savage on each side of me who had killed two of my dear children that day,

I had to pass the first night of my captivity.

Ye mothers, who

have never lost a child by an inhuman savage, or endured the almost indescribable

misery here related, may nevertheless think a little (though it be but little)

what I endured; and hence, now you are enjoying sweet repose and the comforts

of a peaceful and well-replenished habitation, sympathize with me a little,

as one who was a pioneer in the work of cultivation and civilization.

But the trials

and dangers of the day I had passed had so completely exhausted nature, that,

notwithstanding my unpleasant situation, and my determination, to escape if

possible, I insensibly fell asleep, and repeatedly dreamed of my escape and

safe arrival in Pittsburgh, and several things relating to the town, of which

I knew nothing at the time, but found to be true when I arrived there. The

first night passed away, and I found no means of escape, for the savages kept

watch the whole of the night, without any sleep.

In the morning,

one of them left us to watch the trail or path we had come, to see if any

white people were pursuing us. During the absence of the Indian, who was the

one that claimed me, the other, who remained with me, and who was the murderer

of my last boy, took from his bosom his scalp, and prepared a hoop and stretched

the scalp upon it. Those mothers who have not seen the like done by one of

the scalps of their own children, (and few, if any, ever had so much misery

to endure,) will be able to form but faint ideas of the feelings which then

harrowed up my soul! I meditated revenge. While he was in the very act, I

attempted to take his tomahawk, which hung by his side and rested on the ground,

and had nearly succeeded, and was, as I thought, about to give the fatal blow;

when, alas! I was detected.

The savage felt

me at his tomahawk handle, turned round upon me, cursed me, and told me I

was a Yankee; thus insinuating he understood my intention, and to prevent

me from doing so again, faced me. My excuse to him for handling his tomahawk

was, that my child wanted to play with the handle of it. Here again I wondered

at my merciful preservation, for the looks of the savage were terrific in

the extreme; and these, I apprehend, were only an index to his heart. But

God was my preserver.

The savage who

went upon the look-out in the morning came back about 12 o'clock, and had

discovered no pursuers. Then the one who had been guarding me went out on

the same errand. The savage who was now my guard began to examine me about

the white people, the strength of the armies going against them, &c.,

and boasted largely of their achievements in the preceding fall, at the defeat

of General St. Clair.

He then examined

into the plunder which he had brought from our house the day before. He found

my pocket-book and money in his plunder. There were ten dollars in silver,

and a half a guinea, in gold in the book. During this day they gave me a piece

of dry venison, about the bulk of an egg, and a piece about the same size

the day we were marching, for my support and that of my child; but owing to

the blows I had received from them in my jaws, I was unable to eat a bit of

it. I broke it up, and gave it to the child. The savage on the look-out returned

about dark. This evening, (Monday the 23d,) they moved me to another station

in the same valley, and secured me as they did the preceding night. Thus I

found myself the second night between two Indians, without fire or refreshment.

During this night I was frequently asleep, notwithstanding my unpleasant situation,

and as often dreamed of my arrival in Pittsburgh.

Early on the

morning of the 24th, a flock of mocking birds and robins hoverd over us, as

we lay in our uncomfortable bed, and sung, and said, at least to my imagination,

that I was to get up and go off. As soon as day broke, one of the Indians

went off again to watch the trail, as on the preceding day, and he who was

left to take care of me, appeared to be sleeping. When I perceived this, I

lay still and began to snore as though asleep, and he fell asleep.

Then I concluded

it was time to escape. I found it impossible to injure him for my child at

the breast, as I could not effect any thing without putting the child down,

and then it would cry and give the alarm; so I contented myself with taking

from a pillow-case of plunder, taken from our house, a short gown, handkerchief,

and The savage felt me at his tomahawk handle, turned round upon me, cursed

me, and told me I was a Yankee; thus insinuating he understood my intention,

and to prevent me from doing so again, faced me. My excuse to him for handling

his tomahawk was, that my child wanted to play with the handle of it. Here

again I wondered at my merciful preservation, for the looks of the savage

were terrific in the extreme; and these, I apprehend, were only an index to

his heart. But God was my preserver.

The savage who

went upon the look-out in the morning came back about 12 o'clock, and had

discovered no pursuers. Then the one who had been guarding me went out on

the same errand. The savage who was now my guard began to examine me about

the white people, the strength of the armies going against them, &c.,

and boasted largely of their achievements in the preceding fall, at the defeat

of General St. Clair.

He then examined

into the plunder which he had brought from our house the day before. He found

my pocket-book and money in his plunder. There were ten dollars in silver,

and a half a guinea; in gold in the book. During this day they gave me a piece

of dry venison, about the bulk of an egg, and a piece about the same size

the day we were marching, for my support and that of my child; but owing to

the blows I had received from them in my jaws, I was unable to eat a bit of

it. I broke it up, and gave it to the child. The savage on the look-out returned

about dark. This evening, (Monday the 23d,) they moved me to another station

in the same valley, and secured me as they did the preceding night. Thus I

found myself the second night between two Indians, without fire or refreshment.

During this night I was frequently asleep, notwithstanding my unpleasant situation,

and as often dreamed of my arrival in Pittsburgh.

Early on the

morning of the 24th, a flock of mocking birds and robins hoverd over us, as

we lay in our uncomfortable bed, and sung, and said, at least to my imagination,

that I was to get up and go off. As soon as day broke, one of the Indians

went off again to watch the trail, as on the preceding day, and he who was

left to take care of me, appeared to be sleeping. When I perceived this, I

lay still and began to snore as though asleep, and he fell asleep.

Then I concluded

it was time to escape. I found it impossible to injure him for my child at

the breast, as I could not effect any thing without putting the child down,

and then it would cry and give the alarm; so I contented myself with taking

from a pillow-case of plunder, taken from our house, a short gown, handkerchief,

and child's frock, and so made ray escape ; the sun then being about, half

an hour high.

I took a direction

from home, at first, being guided by the birds before mentioned, and in order

to deceive the Indians, then took over the hill, and struck the Connequenessing

creek about two miles from where I crossed it with the Indians, and went down

the stream till about two o'clock in the afternoon, over rocks, precipices,

thorns, briars, &c., with my bare feet and legs. I then discovered by

the sun, and the running of the stream, that I was on the wrong course, and

going from, instead of coming nearer home. I then changed my course, ascended

a hill, and sat down till sunset, and the evening star made its appearance,

when I discovered the way I should travel; and having marked out the direction

I intended to take the next morning, I collected some leaves, made up a bed

and laid myself down and slept, though my feet being full of thorns, began

to be very painful, and I had nothing still to eat for myself or child.

The next morning,

(Friday, 25th of May) about the breaking of the day I was aroused from my

slumbers by the flock of birds before mentioned, which still continued with

me, and having them to guide me through the wilderness. As soon as it was

sufficiently light for me to find my way, I started for the fourth day's trial

of hunger and fatigue.

There was nothing

very material occurred on this day while I was travelling, and I made the

best of my way, according to my knowledge, towards the Alleghany river. In

the evening, about the going down of the sun, a moderate rain came on, and

I began to prepare for my bed by collecting some leaves together, as I had

done the night before ; but could not collect a sufficient quantity without

setting my little boy on the ground ; but as soon as I put him out of my arms

he began to cry. Fearful of the consequence of his noise in this situation,

I took him in my arms, and put him to the breast immediately, and he became

quiet. I then stood and listened, and distinctly heard the footsteps of a

man coming after me in the same direction I had come! The ground over which

I had been travelling was good, and the mould was light; I had therefore left

my footmarks, and thus exposed myself to a second captivity ! Alarmed at my

perilous situation, I looked around for a place of safety, and providentially

discovered a large tree which had fallen, into the tops of which I crept,

with my child in my arms, and there hid myself securely under the limbs. The

darkness of the night greatly assisted me, and prevented me from detection.

The footsteps

I heard were those of a savage. He heard the cry of the child, and came to

the very spot where the child cried, and there he halted, put down his gun,

and was at this time so near that I heard the wiping stick strike against

his gun distinctly.

My getting in

under the tree, and sheltering myself from the rain, and pressing my boy to

my bosom, got him warm, and most providentially he fell asleep, and lay very

still during the time of my danger at that time. All was still and quiet,

the savage was listening if by possibility he might again hear the cry he

had heard before. My own heart was the only thing I feared, and that beat

so loud that I was apprehensive it would betray me. It is almost impossible

to conceive or to believe the wonderful effect my situation produced upon

my whole system.

After the savage

had stood and listened with nearly the stillness of death for two hours, the

sound of a bell, and a cry like that of a night-owl, signals which were given

to him from his savage companions, induced him to answer, and after he had

given a most horrid yell, which was calculated to harrow up my soul, he started,

and went off to join them.

After the retreat

of the savage to his companions, I concluded it unsafe to remain in my concealed

situation till morning, lest they should conclude upon a second search, and

being favored with the light of day, find me, and either tomahawk, or scalp

me, or otherwise bear me back to my captivity again, which was worse than

death.

But by this time

nature was nearly exhausted, and I found some difficulty in moving from my

situation that night; yet, compelled by necessity and a love of self-preservation,

I threw my coat about my child, and placed the end between my teeth, and with

one arm and my teeth I carried the child, and with the other arm groped my

way between the trees, and travelled on as I supposed a mile or two, and there

sat down at the root of a tree till the morning. The night was cold and wet;

and thus terminated the fourth day and night's difficulties, trials, hunger,

and danger.

The fifth day,

Saturday, 26th May, wet and exhausted, hungry and wretched, I started from

my resting-place in the morning as soon as I could see my way, and on that

morning struck the head waters of Pine Creek, which falls into the Alleghany

about four miles above Pittsburgh ; though I knew not then what waters they

were, but crossed them, and on the opposite bank I found a path, and discovered

in it two mockasin tracks, fresh indented, and the men who had made them were

before me, and travelling on the same direction that I was travelling. This

alarmed me ; but as they were before me, and travelling in the same direction

as I was, I concluded I could see them as soon as they could see me; and therefore

I pressed on in that path for about three miles, when I came to the forks

where another branch empties into the creek, and where was a hunter's camp,

where the two men, whose tracks I had before discovered and followed, had

been, and kindled a fire and breakfasted, and had left the fire burning.

I here became

more alarmed, and came to a determination to leave the path. I then ascended

a hill, and crossed a ridge toward Squaw run, and came upon a trail or path.

Here I stopped and meditated what to do; and while I was thus musing, 1 saw

three deers coming toward me in full speed ; they turned to look at their

pursuers ; I looked too with all attention, and saw the flash of a gun, and

then heard the report as soon as the gun was fired. I saw some dogs start

after them, and began to look about for a shelter, and immediately made for

a large log, and hid myself behind it; but most providentially I did not go

clear to the log; had I done so, I might have lost my life by the bites of

rattle-snakes; for as I put nay hand to the ground to raise myself, that I

might see what was become of the hunters and who they were, I saw a large

heap of rattle-snakes, and the top one was very large, and coiled up very

near my face, and quite ready to bite me. This compelled me to leave this

situation, let the consequences be what they might.

In consequence

of this occurrence, I again left my course, bearing to the left, and came

upon the head waters of Squaw run, and kept down the run the remainder of

that day.

During the day

it rained, and I was in a very deplorable situation ; so cold and shivering

were my limbs, that frequently, in opposition to all my struggles, I gave

an involuntary groan. I suffered intensely this day from hunger, though my

jaws were so far recovered from the injury they sustained from the blows of

the Indians, that wherever I could I procured grape vines, and chewed them

for a little sustenance. In the evening I came within one mile of the Alleghany

river, though I was ignorant of it at the time; and there, at the root of

a tree, through a most tremendous night's rain, I took up my fifth night's

lodgings; and in order to shelter my infant as much as possible, I placed

him in my lap, and placed my head against the tree, and thus let the rain

fall upon me.

On the sixth

(that was Sabbath) morning from my captivity, I found myself unable, for a

very considerable time, to raise myself from the ground ; and when I had once

more, by hard struggling, got myself upon my feet, and started upon the sixth

day's encounter, nature was so nearly exhausted, and my spirits were so completely

depressed, that my progress was amazingly slow and discouraging.

In this almost

helpless condition, I had not gone far before I came to a path where there

had been cattle travelling; I took the path, under the impression that it

would lead me to the abode of some white people, and by travelling it about

one mile, I came to an uninhabited cabin; and though I was in a river bottom,

yet I knew not where I was, nor yet on what river bank I had come. Here I

was seized with the feelings of despair, and under those feelings I went to

the threshold of the uninhabited cabin, and concluded that I would enter and

lie down and die; as death would have been to me an angel of mercy in such

a situation, and would have removed me from all my misery.

Such were my

feelings at this distressing moment, and had it not been for the recollection

of those sufferings which my infant would endure, who would survive for some

time after I was dead, I should have carried my determination into execution.

Here, too, I heard the sound of a cow-bell, which imparted a gleam of hope

to my desponding mind. I followed the sound of the bell till I came opposite

to the fort at the Six Mile Island.

When I came there,

I saw three men on the opposite bank of the river. My feelings at the sight

of these were better felt than described. I called to the men, but they seemed

unwilling to risk the danger of coming after me, and requested to know who

I was. I replied that I was one who had been taken prisoner by the Indians

on the Alleghany river on last Tuesday morning, and had made my escape from

them. They requested me to walk up the bank of the river for a while, that

they might see if the Indians were making a. decoy of me or not; but I replied

to them that my feet were so sore that I could not walk.

Then one of

them, James Closier, got into a canoe to fetch me over, and the other two

stood on the bank, with their rifles cocked, ready to fire on the Indians,

provided they were using me as a decoy. When Mr. Closier came near to the

shore, and saw my haggard and dejected situation, he exclaimed, " who,

in the name of God, are you ?" This man was one of my nearest neighbors

before I was taken ; yet in six days I was so much altered that he did not

know me, either by my voice or my countenance.

When I landed

on the inhabited side of the river, the people from the fort came running

out to the boat to see me : they took the child from me, and now I felt safe

from all danger, I found myself unable to move or to assist myself in any

degree: whereupon the people took me and carried me out of the boat to the

house of Mr. Cortus.

Here, when I

felt I was secure from the ravages and cruelties of the barbarians, for the

first time since my captivity my feelings returned with all their poignancy.

When I was dragged from my bed and from my home, a prisoner with the savages;

when the inhuman butchers dashed the brains of one of my dear children out

on the door-sill, and afterward scalped him before my eyes ; when they took

and tomahawked, scalped, and stabbed another of them before me on the island

; and when, with still more barbarous feelings, they afterward made a hoop,

and stretched his scalp on it; nor yet, when I endured hunger, cold, and nearly

nakedness, and at the same time my infant sucking my very blood to support

it, I never wept. No ! it was too, too much for nature. A tear then would

have been too great a luxury. And it is more than probable, that tears at

these seasons of distress would have been fatal in their consequences ; for

savages despise a tear. But now that my danger was removed, and I was delivered

from the pangs of the barbarians, the tears flowed freely, and imparted a

happiness beyond what I ever experienced before, or ever expect to experience

in this world.

When I was taken

into the house, having been so long from fire, and having endured so much

from hunger for a long period, the heat of the fire, and the smell of the

victuals, which the kindness of the people immediately induced them to provide

for me, caused me to faint. Some of the people attempted to restore me and

some of them put some clothes upon me. But the kindness of these friends would,

in all probability, have killed me, had it not been for the providential arrival

from down the river, of Major M'Culley, who then commanded the line along

the river. When he came in and saw my situation, and the provisions they were

making for me, he became greatly alarmed, and immediately ordered me out of

the house, from the heat and smell; prohibited my taking any thing but the

whey of buttermilk, and that in very small quantities, which he administered

with his own hands. Through this judicious management of my almost lost situation,

I was mercifully restored again to my senses, and very gradually to my health

and strength.

Two of the females,

Sarah Carter and Mary Ann Crozier, then began to take out the thorns from

my feet and legs; and Mr. Felix Negley, who now lives at the mouth of Bull

Creek, twenty miles above Pittsburgh, stood by and counted the thorns as the

women took them out, and there were one hundred and fifty drawn out, though

"they were not all extracted at that time, for the next evening, at Pittsburgh,

there were many more taken out. The flesh was mangled dreadfully, and the

skin and flesh were hanging in pieces on my feet and legs. The wounds were

not healed for a considerable time. Some of the thorns went through my feet

and came out on the top. For two weeks I was unable to put my feet to the

ground to walk.

Besides which,

the rain to which I was exposed by night, and the heat of the sun, to which

my almost naked body was exposed by day, together with my carrying my child

so long in my arms without any relief, and any shelter from the heat of the

day or the storms of the night, caused nearly all the skin of my body to come

off, so that my body was raw nearly all over.

The news of my

arrival at the station spread with great rapidity. The two spies took the

intelligence that evening as far as Coe's station, and the next morning to

Reed's station, to my husband.

As the intelligence

spread, the town of Pittsburgh, and the country for twenty miles round, way

all in a state of commotion. About sunset the same evening, my husband came

to see me in Pittsburgh, and I was taken back to Coe's station on Tuesday

morning. In the evening I gave the account of the murder of my boy on the

island. The next morning (Wednesday) there was a scout went out, and found

it by my direction, and buried it, after being murdered nine days.

Copy of a Letter

from Mr. JOHN CORBLY, a Baptist Minister, to his friend in Philadelphia, dated

Muddy Creek Penn, Sept. 1, 1792.

"DEAR Sir,

" The following

are the particulars! of the destruction of my unfortunate family by the savages

:- On the 10th May last, being my appointment to preach at one of my meeting

houses, about a mile from my dwelling-house, I set out with my loving wife

and five children for public worship. Not suspecting any danger, I walked

behind a few rods, with ray Bible in my hand, meditating. As I was thus employed,

on a sudden I was greatly alarmed by the shrieks of my dear family before

me. I immediately ran to their relief with all possible speed, vainly hunting

a club as I ran. When within a few yards of them, my poor wife observing me,

cried out to me to make my escape. At this instant an Indian ran up to shoot

me. I had to strip, and by so doing outran him. My wife had an infant in her

arms, which the Indians killed and scalped; After which they struck my wife

several times, but not bringing her to the ground, the Indian who attempted

to shoot me approached her, and shot her through the body ; after which they

scalped her. My little son, about six years old, they dispatched by sinking

their hatchets in his brains. My little daughter, four years old, they in

like manner tomahawked and scalped. My eldest daughter attempted an escape

by concealing herself in a hollow tree, about six rods from the fatal scene

of action. Observing the Indians retiring, as she supposed, she deliberately

crept from the place of her concealment, when one of the Indians, who yet

remained on the ground, espying her, ran up to her, and with his tomahawk

knocked down and scalped her. But, blessed be God, she yet survives, as does

her little sister whom the savages in the like manner tomahawked and scalped.

They are mangled to a shocking degree, but the doctors think there are some

hopes of their recovery.

" When I

supposed the Indians gone, I returned to see what had become of my unfortunate

family, whom, alas ! I found in the situation above described. No one, my

dear friend, can form a true conception of my feelings at this moment. A view

of a scene so shocking to humanity quite overcome me. I fainted, and was unconsciously

borne off by a friend, who at that instant arrived to my relief. " Thus,

dear sir, have I given you a faithful, though a short narrative of the fatal

catastrophe; amidst which my life is spared, but for what purpose the Great

Jehovah best knows. Oh, may I spend it to the praise and glory of His grace,

who worketh all things after the counsel of his own will. The government of

the world and the church is in his hands. I conclude with wishing you every

blessing, and subscribe myself your affectionate though afflicted friend,

and unworthy brother in the gospel ministry,

" JOHN CORBLY"

No. IX.

[REFERENCE FROM PAGE 376.]

Miamis Rapids, May 7th, 1794.

Two Deputies from the Three Nations of the Glaize arrived here yesterday,

with a speech from the Spaniards, brought by the Delawares residing near their

posts, which was repeated in a council held this day, to the following nations

now at this place, viz:-

Wyandots, Mingoes,

Ottawas, Munseys,

Chippawas, Nanticokes.

GRAND-CHILDREN

AND BRETHREN,

We are just arrived from the Spanish settlements upon the Mississippi, and

are come to inform you what they have said to us in a late council. These

are their words :

Children Delawares,

Six Strings White Wampum.

" Pointing

to this country." When you first came from that country to ask my protection,

and when you told me you had escaped from the heat of a great fire that was

like to scorch you to death, I took you by the hand and under my protection,

and told you to look about for a piece of land to hunt on and plant for the

support of yourselves and families in this country, which the Great Spirit

had given for our mutual benefit and support. I told you at the same time

that I would watch over it, and when any thing threatened us with danger,

that I would immediately speak to you ; and that when I did speak to you,

that it would behove you to be strong and listen to my words. Delivered six

Strings White Wampum.

The Spaniard

then, addressing himself to all the nations who were present, said,

CHILDREN, These

were my words to all the nations here present, as well as to your grand-fathers,

the Delawares. Now, Children, I have called you together to communicate to

you certain intelligence of a large force assembling on the Shawanoe river

to invade our country. It has given me very great satisfaction to observe

the strong confederacy formed among you, and I have no doubt of your ready

assistance to repel this force.

CHILDREN, You

see me now on my feet, and grasping the tomahawk to strike them.

CHILDREN, We

will strike them together. I do not desire you to go before me, in the front,

but to follow me. These people have too long disturbed our country, and have

extinguished many of our council-fires. They are but a trifling people compared

to the white people now combined against them, and determined to crush them

for their evil deeds. They must by this time be surrounded with enemies, as

all the white nations are against them. Your French Father also speaks through

me to you on this occasion, and tells you that those of his subjects who have

joined the Big-knives, are only a few of his disobedient children who have

joined the disobedient in this country ; but as we are strong and unanimous,

we hope, by the assistance of the Great Spirit, to put a stop to their mischievous

designs. Delivered a bunch Black Wampum.

CHILDREN, Now

I present you with a war-pipe, which has been sent in all our names to the

Musquakies, and all those nations who live toward the setting of the sun,

to get upon their feet and take hold of our tomahawk; and as soon as they

smoked it they sent it back, with a promise to get immediately on their feet

to join us and strike this enemy. Their particular answer to me was as follows

:

" FATHER,

We have long seen the designs of the Big-knives against our country, and also

of some of our own color, particularly the Kaskaskies, who have always spoke

with the same tongue as the Big-knives. They must not escape our revenge ;

nor must you, Father, endeavor to prevent our extirpating them. Two other

tribes of our color, the Piankishaws and the Cayaughkiaas, who have been strongly

attached to our enemies the Big-knives, shall share the same fate with the

Kaskaskies."

CHILDREN, You

hear what these distant nations have said to us, so that we have nothing farther

to do but put our designs in immediate execution, and to forward this pipe

to the three warlike nations who have so long been struggling for their country,

and who now sit at the Glaize. Tell them to smoke this pipe, and to forward

it to all the Lake Indians and their northern brethren ; then nothing will

be wanting to complete our general union from the rising to the setting of

the sun, and all nations will be ready to add strength to the blow we are

going to make. Delivered a War Pipe.

CHILDREN, I now

deliver you a Message from the Creeks, Cherokees, and Choctaws and Chickasaws,

who desire you to be strong in uniting yourselves; and tell you it has given

them pleasure to hear you have been so unanimous in listening to your Spanish

Father ; and they acquaint you that their hearts are joined to ours, and that

there are eleven nations of the southern Indians now on their feet, with the

hatchet in their hand, ready to strike our common enemy. Black Strings of

Wampum.

The Deputies

of the Three Nations of the Glaize, after speaking the above speeches from

the Spaniards, addressed themselves to the several nations in council, in

the following manner:

BROTHERS, You

have now heard the speeches brought to our council at the Glaize a few days

ago from the Spaniards, and as soon as they heard them and smoked the pipe,

their hearts were glad, and they determined to step forward and put into execution

the advice sent them. They desire you to forward the pipe, as has been recommended,

to all our northern brethren, not doubting but as soon as you have smoked

it, you will follow their example ; and they will hourly expect you to join

them, as it will not be many days before the nearness of our enemies will

give us an opportunity of striking them. Delivered the Pipe.

BROTHERS, Our

Grand-fathers, the Delawares, spoke first in our late council at the Glaize,

on this piece of painted tobacco and this painted Black Wampum, and expressed

their happiness at what they had heard from their Spanish Father and their

brethren to the Westward, and desired us to tell you to forward this tobacco

and Wampum to the Wyandots, to be sent to all the Lake Indians, and inform

them that in eight days they would be ready to go against the Virginians,

who are now so near us, and that according to the number of Indians collected,

they would either engage the army or attemptto cut off their supplies. The

Delawares also desired us to say to the Wyandots, that, as they are our elder