CHAPTER XIV.

E

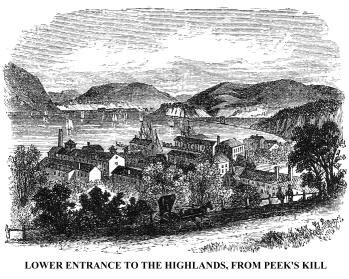

rowed to Garrison's, where we dismissed the waterman, and took the cars for

Peek's Kill, six miles below, a pleasant village lying at the river opening

of a high and beautiful valley, and upon slopes that overlook a broad bay

and extensive mountain ranges.* We passed the night at the house of a friend

(Owen T. Coffin, Esq.), and from the lawn in front of his dwelling, which

commands the finest view of the river and mountains in that vicinity, made

the sketch of the Lower Entrance to the Highlands. On the left is seen the

Donder Berg, over and behind which Sir Henry Clinton's army marched to attack

Forts Clinton and Montgomery. On the right is Anthony's Nose, with the site

of Fort Independence between it and Peek's Kill; and in the centre is Bear

Mountain, at whose base is the beautiful Lake Sinnipink--the "Bloody

Pond" in revolutionary times. This view includes a theatre of most important

historical events. We may only glance at them.

E

rowed to Garrison's, where we dismissed the waterman, and took the cars for

Peek's Kill, six miles below, a pleasant village lying at the river opening

of a high and beautiful valley, and upon slopes that overlook a broad bay

and extensive mountain ranges.* We passed the night at the house of a friend

(Owen T. Coffin, Esq.), and from the lawn in front of his dwelling, which

commands the finest view of the river and mountains in that vicinity, made

the sketch of the Lower Entrance to the Highlands. On the left is seen the

Donder Berg, over and behind which Sir Henry Clinton's army marched to attack

Forts Clinton and Montgomery. On the right is Anthony's Nose, with the site

of Fort Independence between it and Peek's Kill; and in the centre is Bear

Mountain, at whose base is the beautiful Lake Sinnipink--the "Bloody

Pond" in revolutionary times. This view includes a theatre of most important

historical events. We may only glance at them.

Peek's Kill, named from the "Kill of Jan Peek," that

flows into the Hudson just above the rocky promontory on the north-western

side of the town, was an American depôt of military stores, during the

earlier years of the war for independence. These were destroyed and the post

burnt by the British in the spring of 1777. There, during most of the war,

was the head-quarters of important divisions of the revolutionary army, and

there the British spy was hanged, concerning whom General Putnam wrote his

famous laconic letter to Sir Henry Clinton. The latter claimed the offender

as a British officer, when Putnam wrote in reply:--

"Head-quarters, 7th August, 1777.

" Sir,-- Edmund Palmer, an officer in the enemy's service, was taken as a spy, lurking within our lines. He has been tried as a spy, condemned as a spy, and shall be executed as a spy; and the flag is ordered to depart immediately.

" Israel Putnam. "

"P.S.--He has been accordingly executed."

At

Peek's Kill we procured a waterman, whose father, then eighty-five years of

age, conveyed the writer across the King's Ferry, four or five miles below,

twelve years before. The morning was cool, and a stiff breeze was blowing

from the north. We crossed the bay, and entered Fort Montgomery Creek (anciently

Poplopen's Kill) between the two rocky promontories on which stood Forts Clinton

and Montgomery, within rifle-shot of each other. The banks of the creek are

high and precipitous, the southern one covered with trees; and less than half

a mile from its broad and deep mouth, in which large vessels may anchor, it

is a wild mountain stream, rushing into the placid tide-water through narrow

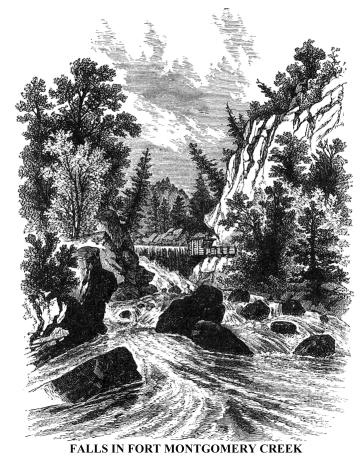

valleys and dark ravines. Here, at the foot of a wild cascade, we moored our

little

At

Peek's Kill we procured a waterman, whose father, then eighty-five years of

age, conveyed the writer across the King's Ferry, four or five miles below,

twelve years before. The morning was cool, and a stiff breeze was blowing

from the north. We crossed the bay, and entered Fort Montgomery Creek (anciently

Poplopen's Kill) between the two rocky promontories on which stood Forts Clinton

and Montgomery, within rifle-shot of each other. The banks of the creek are

high and precipitous, the southern one covered with trees; and less than half

a mile from its broad and deep mouth, in which large vessels may anchor, it

is a wild mountain stream, rushing into the placid tide-water through narrow

valleys and dark ravines. Here, at the foot of a wild cascade, we moored our

little boat,

and sketched the scene. A short dam has been constructed there for sending

water through a flume to a mill a few rods below. This stream, like Indian

Brook, presents a thousand charming pictures, where nature woos her lovers

in the pleasant summer-time.

boat,

and sketched the scene. A short dam has been constructed there for sending

water through a flume to a mill a few rods below. This stream, like Indian

Brook, presents a thousand charming pictures, where nature woos her lovers

in the pleasant summer-time.

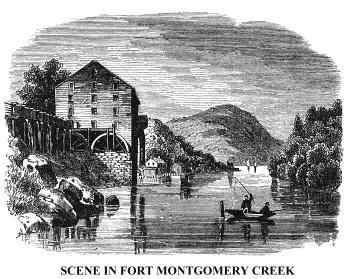

From the mill may be obtained a view of the promontories on

each side of the creek, and of the lofty Anthony's Nose on the eastern side

of the river, which appears in our sketch, dark and imposing, as we look toward

the east. Fort Montgomery was on the northern side of the creek, and Fort

Clinton on the southern side. They were constructed at the beginning of the

war for independence, and became the theatre of a desperate and bloody contest

in the autumn of 1777. They were strong fortresses, though feebly manned.

From Fort Montgomery to Anthony's Nose a heavy boom and massive iron chain

were stretched over the river, to obstruct British ships that might attempt

a passage toward West Point. The two forts were respectively commanded by

two brothers, Generals  George

and James Clinton, the former at that time governor of the newly organized

State of New York.

George

and James Clinton, the former at that time governor of the newly organized

State of New York.

Burgoyne, then surrounded by the Americans at Saratoga, was,

as we have observed in a former chapter, in daily expectation of a diversion

in his favour, on the Lower Hudson, by Sir Henry Clinton--in command of the

British troops at New York. Early in October, the latter fitted out an expedition

for the Highlands, and accompanied it in person. He deceived General Putnam,

then in command at Peck's Kill, by feints on that side of the river, at the

same time he sent detachments over the Donder Berg, under cover of a fog.

They were piloted by a resident Tory or loyalist, and in the afternoon of

the 6th of October, and in two divisions, fell upon the forts. The commanders

of the forts had no suspicions of the proximity of the enemy until their picket

guards were assailed. These, and a detachment sent out in that  direction,

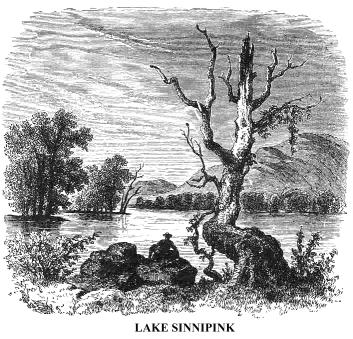

had a severe skirmish with the invaders on the borders of Lake Sinnipink,

a beautiful sheet of water lying at the foot of the lofty Bear Mountain, on

the same general level as the foundations of the fort. Many of the dead were

cast into that lake, near its outlet, and their blood so incarnadined its

waters, that it has ever since been vulgarly called "Bloody Pond."

direction,

had a severe skirmish with the invaders on the borders of Lake Sinnipink,

a beautiful sheet of water lying at the foot of the lofty Bear Mountain, on

the same general level as the foundations of the fort. Many of the dead were

cast into that lake, near its outlet, and their blood so incarnadined its

waters, that it has ever since been vulgarly called "Bloody Pond."

The garrisons at the two forts, meanwhile, prepared to resist the attack with desperation. They were completely invested at four o'clock in the afternoon, when a general contest commenced, in which British vessels in the river participated. It continued until twilight. The Americans then gave way, and a general flight ensued. The two commanders were among those who escaped to the mountains. The Americans lost in killed, wounded, and prisoners, about three hundred. The British loss was about one hundred and forty.

The contest ended with a sublime spectacle. Above the boom and chain the Americans had two frigates, two galleys, and an armed sloop. On the fall of the forts, the crews of these vessels spread their sails, and, slipping their cables, attempted to escape up the river. But the wind was adverse, and they were compelled to abandon them. They set them on fire when they left, to prevent their falling into the hands of an enemy. "The flames suddenly broke forth," wrote Stedman, a British officer and author, "and, as every sail was set, the vessels soon became magnificent pyramids of fire. The reflection on the steep face of the opposite mountain (Anthony's Nose), and the long train of ruddy light which shone upon the water for a prodigious distance, had a wonderful effect; while the ear was awfully filled with the continued echoes from the rocky shores, as the flames gradually reached the loaded cannons. The whole was sublimely terminated by the explosions, which left all again in darkness."

Early on the following morning, the obstructions in the river, which had cost the Americans a quarter of a million of dollars, continental money, were destroyed by the British fleet. Fort Constitution, opposite West Point, was abandoned. A free passage of the Hudson being opened, Vaughan and Wallace sailed up the river on their destructive errand to Kingston and Clermont, already mentioned.

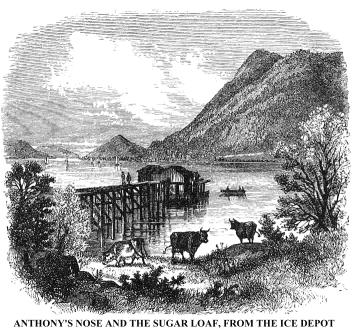

A short distance below Montgomery Creek, at the mouth of Lake Sinnipink Brook, is one of the depots of the Knickerbocker Ice Company, of New York. The spacious storehouses for the ice are on the rocky bank, thirty or forty feet above the river. The ice, cut in blocks from the lake above in winter, is sent down upon wooden "ways," that wind through the forest with a gentle inclination, from the outlet of Sinnipink, for nearly half a mile. A portion of the "ways," from the storehouses to the forwarding depôt below, is seen in our sketch. From that depôt the ice is conveyed into vessels in warm weather, and carried to market. More than thirty thousand tons of ice are annually shipped from this single depôt. Ice is an important article of the commerce of the Hudson, from whose surface, also, immense quantities are gathered every winter.

From

the high bank above the ice depôt, a very fine view of Anthony's Nose

and the Sugar Loaf in the distance may be obtained. The latter name the reader

will remember as that of the lofty eminence in the rear of the Beverly House.

At West Point and its vicinity it forms a long range of mountains, but looking

up from the neighbourhood of the Nose, it is a perfect pyramid in form. It

is one of the first objects that attract the eye of the voyager, when turning

the point of the Nose on entering the Highlands from below. Its form suggested

to the practical minds of the Dutch a Suyeker Broodt--Sugar Loaf--and

so they named it.

From

the high bank above the ice depôt, a very fine view of Anthony's Nose

and the Sugar Loaf in the distance may be obtained. The latter name the reader

will remember as that of the lofty eminence in the rear of the Beverly House.

At West Point and its vicinity it forms a long range of mountains, but looking

up from the neighbourhood of the Nose, it is a perfect pyramid in form. It

is one of the first objects that attract the eye of the voyager, when turning

the point of the Nose on entering the Highlands from below. Its form suggested

to the practical minds of the Dutch a Suyeker Broodt--Sugar Loaf--and

so they named it.

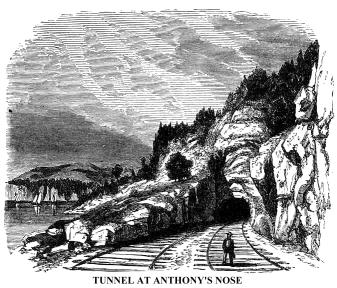

We crossed the river from Lake Sinnipink to Anthony's Nose, through the point of which the Hudson River Railway passes, in a tunnel over two hundred feet in length. This is a lofty rocky promontory, whose summit is almost thirteen hundred feet above the river, and with the jutting point of the Donder Berg, a mile and a half below, gives the Hudson there a double curve, and the appearance of an arm of the sea, terminating at the mountains. Such was the opinion of Hendrick Hudson, as he approached this point from below. The true origin of the name of this promontory is unknown. Irving makes the veracious historian, Diedrich Knickerbocker, throw light upon the subject:--

"And now I am going to tell a fact, which I doubt much

my readers will hesitate to believe, but if  they

do they are welcome not to believe a word in this whole history--for nothing

which it contains is more true. It must be known then that the nose of Anthony

the trumpeter was of a very lusty size, strutting boldly from his countenance

like a mountain of Golconda, being sumptuously bedecked with rubies and other

precious stones--the true regalia of a king of good fellows, which jolly Bacchus

grants to all who bouse it heartily at the flagon. Now thus it happened, that

bright and early in the morning, the good Anthony, having washed his burly

visage, was leaning over the quarter railing of the galley, contemplating

it in the glassy wave below. Just at this moment the illustrious sun, breaking

in all his splendour from behind a high bluff of the Highlands, did dart one

of his most potent beams full upon the refulgent nose of the sounder of brass--the

reflection of which shot straightway down hissing hot into the water, and

killed a mighty sturgeon that was sporting beside the vessel. This huge monster,

being with infinite labour hoisted on board, furnished a luxurious repast

to all the crew, being accounted of excellent flavour excepting about the

wound, where it smacked a little of brimstone--and this, on my veracity, was

the first time that ever sturgeon was eaten in these parts by Christian people.

When this astonishing miracle became known to Peter Stuyvesant, and that he

tasted of the unknown fish, he, as may well be supposed, marvelled exceedingly;

and as a monument thereof, he gave the name of Anthony's Nose to a stout promontory

in the neighbourhood, and it has continued to be called Anthony's Nose ever

since that time."

they

do they are welcome not to believe a word in this whole history--for nothing

which it contains is more true. It must be known then that the nose of Anthony

the trumpeter was of a very lusty size, strutting boldly from his countenance

like a mountain of Golconda, being sumptuously bedecked with rubies and other

precious stones--the true regalia of a king of good fellows, which jolly Bacchus

grants to all who bouse it heartily at the flagon. Now thus it happened, that

bright and early in the morning, the good Anthony, having washed his burly

visage, was leaning over the quarter railing of the galley, contemplating

it in the glassy wave below. Just at this moment the illustrious sun, breaking

in all his splendour from behind a high bluff of the Highlands, did dart one

of his most potent beams full upon the refulgent nose of the sounder of brass--the

reflection of which shot straightway down hissing hot into the water, and

killed a mighty sturgeon that was sporting beside the vessel. This huge monster,

being with infinite labour hoisted on board, furnished a luxurious repast

to all the crew, being accounted of excellent flavour excepting about the

wound, where it smacked a little of brimstone--and this, on my veracity, was

the first time that ever sturgeon was eaten in these parts by Christian people.

When this astonishing miracle became known to Peter Stuyvesant, and that he

tasted of the unknown fish, he, as may well be supposed, marvelled exceedingly;

and as a monument thereof, he gave the name of Anthony's Nose to a stout promontory

in the neighbourhood, and it has continued to be called Anthony's Nose ever

since that time."

Down the steep rocky valley between Anthony's Nose and a summit almost as lofty half a mile below, one of the wildest streams of this region flows in gentle cascades in dry weather, but as a rushing torrent during rain-storms or the time of the melting of the snows in spring. The Dutch called it Brocken Kill, or Broken Creek, it being seen in "bits" as it finds its way among the rocks and shrubbery to the river. The name is now corrupted to Brockey Kill. It is extremely picturesque from every point of view, especially when seen glittering in the evening sun. It comes from a wild wet region among the hills, where the Rattlesnake,* the most venomous serpent of the American continent, abounds. They are found in all parts of the Highlands, but in far less abundance than formerly. Indeed they are now so seldom seen, that the tourist need have no dread of them.

* The Crotalus Durissus, or common northern Rattlesnake of the United States, is of a yellowish or reddish brown, sometimes of a chestnut black, with irregular rhombiodal black blotches; head large, flattened, and triangular; length from three to seven or eight feet. On the tail is a rattle, consisting of several horny enlargements, loosely attached to each other, making a loud rattling sound when shaken and rubbed against each other. These are used by the serpent to give warning of its presence. When disturbed, it throws itself into a coil, vibrates its rattles, and then springing, sometimes four or five feet, fixes its deadly fangs in its victim. It feeds on birds, rabbits, squirrels., &c.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.