CHAPTER XV, Part TWO.

From

the lighthouse is a comprehensive view of Verplanck's Point opposite, whereon

no vestige of Fort Fayette now remains. A little village, pleasant pastures

and tilled fields in summer, and brick manufactories the year round, now occupy

the places of former structures of war, around which the soil still yields

an occasional ball, and bomb, and musket shot. The Indians called this place

Me-a-nagh. They sold it to Stephen Van Cortlandt, in the year 1683,

with land east of it called Ap-pa-magh-pogh. The purchase was confirmed

by patent from the English government. On this point Colonel Livingston held

command a the time of Arnold's treason, in 1780; and here were the head-quarters

of Washington for some time in 1782. It was off this point that Henry Hudson

first anchored the Half-Moon after leaving Yonkers. The Highland

Indians flocked to the vessel in great numbers. One of them was killed in

an affray, and this circumstance planted the seed of hatred of the white man

in the bosom of the Indians in that region.

From

the lighthouse is a comprehensive view of Verplanck's Point opposite, whereon

no vestige of Fort Fayette now remains. A little village, pleasant pastures

and tilled fields in summer, and brick manufactories the year round, now occupy

the places of former structures of war, around which the soil still yields

an occasional ball, and bomb, and musket shot. The Indians called this place

Me-a-nagh. They sold it to Stephen Van Cortlandt, in the year 1683,

with land east of it called Ap-pa-magh-pogh. The purchase was confirmed

by patent from the English government. On this point Colonel Livingston held

command a the time of Arnold's treason, in 1780; and here were the head-quarters

of Washington for some time in 1782. It was off this point that Henry Hudson

first anchored the Half-Moon after leaving Yonkers. The Highland

Indians flocked to the vessel in great numbers. One of them was killed in

an affray, and this circumstance planted the seed of hatred of the white man

in the bosom of the Indians in that region.

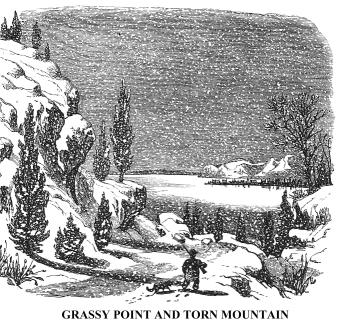

From the southern slope of Stony Point, where the rocks lay in wild confusion, a fine view of Grassy Point, Brewster's Cove, Haverstraw Bay, the Torn Mountain, and the surrounding country may be obtained. The little village of Grassy Point, where brick-making is the staple industrial pursuit, appeared like a dark tongue thrust out from the surrounding whiteness. Haverstraw Bay, which swarms in summer with water-craft of every kind, lay on the left, in glittering solitude beneath the wintry clouds that gathered while I was there, and east down a thick, fierce, blinding snow-shower, quite unlike that described by Bryant, when he sung--

"Here delicate snow-stars out of the cloud,

Come floating downward in airy play,

Like spangles dropped from the glistening crowd

That whiten by night the milky way;

There broader and burlier masses fall;

The sullen water buries them all:

Flake after flake.

All drowned in the dark and silent lake."

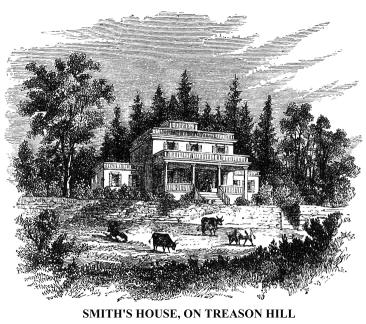

The snow-shower soon passed by. The spires of Haverstraw appeared in the distance, at the foot of the mountain, and on the right was Treason Hill, with the famous mansion of Joshua Hett Smith, who was involved in the odium of Arnold's attempt to betray his country.

Here I will recall the memories of a visit there at the close of a pleasant summer day, several years ago. I had lingered upon Stony Point, until near sunset, listening to the stories of an old waterman, then eighty-five years of age, who assisted in building the fort, and then I started on foot for Haverstraw. I stopped frequently to view the beautiful prospect of river and country on the east, while the outlines of the distant shores were imperceptibly fading as the twilight came on. At dusk I passed an acre of ground, lying by the road-side, which was given some years before as a burial-place for the neighbourhood. It was already populous. The lines of Longfellow were suggested and pondered. He says,--

"I like that ancient Saxon phrase which calls

The burial-ground God's Acre! It Is just;

It consecrates each grave within its walls,

And breathes a benison o'er the sleeping dust.

"God's Acre! Yes, that blessed name imparts

Comfort to those who in the grave have sown

The seed that they had garner'd in their hearts,

Their bread of life, alas! no more their own."

Night had fallen when I reached Treason Hill, so I passed on to the village near. Early on the following morning, before the dew had left the grass, I sketched Smith's House, where Arnold and André completed those negotiations concerning the delivery, by the former, of West Point and its defenders into the hands of the British, for a mercenary consideration, which led to the death of one, and the eternal infamy of the other.

The story of Arnold's treason may be briefly told. We have had occasion to allude to it several times already.

Arnold was a brave soldier, but a bad man. He was wicked in

boyhood, and in early manhood  his

conduct was marked by traits that promised ultimate disgrace. Impulsive, vindictive,

and unscrupulous, he was personally unpopular, and was seldom without a quarrel

with some of his companions in arms. This led to continual irritations, and

his ambitious aims were often thwarted. He fought nobly for freedom during

the earlier years of the war, but at last his passions gained the mastery

over his judgment and conscience.

his

conduct was marked by traits that promised ultimate disgrace. Impulsive, vindictive,

and unscrupulous, he was personally unpopular, and was seldom without a quarrel

with some of his companions in arms. This led to continual irritations, and

his ambitious aims were often thwarted. He fought nobly for freedom during

the earlier years of the war, but at last his passions gained the mastery

over his judgment and conscience.

Arnold twice received honourable wounds during the war--one at Quebec, the other almost two years later at Saratoga;* both were in the leg. The one last received, while gallantly fighting the troops of Burgoyne, was not yet heated when, in the spring of 1778, the British army, under Sir Henry Clinton, evacuated Philadelphia, and the Americans, under Washington, came from their huts at Valley Forge to take their places. Arnold, not being able to do active duty in the field, was appointed military governor of Philadelphia. Fond of display, he there entered upon a course of extravagant living that was instrumental in his ruin. He made his head-quarters at the fine old mansion built by William Penn, kept a coach and four, gave splendid dinner parties, and charmed the gayer portions of Philadelphia society with his princely display. His station and the splendour of his equipage captivated the daughter of Edward Shippen, a leading loyalist, and afterwards chief justice of Pennsylvania; she was then only eighteen years of age. Her beauty and accomplishments won the heart of the widower of forty. They were married. Staunch Whigs shook their heads in doubt concerning the alliance of an American general with a leading Tory family.

* Soon after Arnold joined the British Army, he was sent with a considerable force upon a marauding expedition up the James River, in Virginia. In an action not far from Richmond, the capital, some Americans were made prisoners. He asked one of them what his countrymen would do with him (Arnold) if they should catch him. The prisoner instantly replied, "Bury the leg that was wounded at Quebec and Saratoga with military honours, and hand the remainder of you."

Arnold's extravagance soon brought numerous creditors to his door. Rather than retrench his expenses he procured money by a system of fraud and prostitution of his official power: the city being under martial law, his will was supreme. The people became incensed, and official inquiries into his conduct were instituted, first by the local state council, and then by the Continental Congress. The latter body referred the whole matter to Washington. The accused was tried by court-martial, and he was found guilty of two of four charges. The court passed the mildest sentence possible--a mere reprimand by the commander-in-chief. This duty Washington performed in the most delicate manner. "Our profession," he said, "is the chastest of all; even the shadow of a fault tarnishes the lustre of our finest achievements. The least inadvertence may rob us of the public favour, so hard to be acquired. I reprimand you for having forgotten that, in proportion as you had rendered yourself formidable to our enemies, you should have been guarded and temperate in your deportment towards your fellow citizens. Exhibit anew those noble qualities which have placed you on the list of our most valued commanders. I will myself furnish you, as far as it may be in my power, with opportunities of regaining the esteem of your country."

What punishment could have been lighter? yet Arnold was greatly irritated. A year had elapsed since his accusation, and he expected a full acquittal. But for nine months the rank weeds of treason had been growing luxuriantly in his heart. He saw no way to extricate himself from debt, and retain his position in the army. For nine months he had been in secret correspondence with British officers in New York. His pride was now wounded, his vindictive spirit was aroused, and he resolved to sell his country for gold and military rank. He opened a correspondence in a disguised hand, and in commercial phrase, with Major John André, the young and highly accomplished adjutant-general of the British army.

How far Mrs. Arnold (who had been quite intimate with Major André in Philadelphia, and had kept up an epistolary correspondence with him after the British army had left that city) was implicated in these treasonable communications we shall never know. Justice compels us to say that there is no evidence of her having had any knowledge of the transaction until the explosion of the plot at Beverly already mentioned.

Arnold's deportment now suddenly changed. For a long time he had been sullen and indifferent; now his patriotism glowed with all the apparent ardour of his earlier career. Hitherto he had pleaded the bad state of his wounds as an excuse for inaction; now they healed rapidly. He appeared anxious to join his old companions in arms: and to General Schuyler, and other influential men, then in Congress, he expressed an ardent desire to be in the camp or in the field. They believed him to be sincere, and rejoiced. They wrote cheering letters to Washington on the subject; and, pursuant to Arnold's intimation, they suggested the propriety of appointing him to the command of West Point, the most important post in the country. Arnold visited Washington's camp at the same time, and, in a modest way, expressed a desire to have a command like that of West Point, as his wounds would not permit him to perform very active service on horseback.

The change surprised Washington, yet he was unsuspicious of wrong. He gave Arnold the command of "West Point and its dependencies," and furnished him with written instructions on the 3rd of August, 1780. Then it was that Arnold made his head-quarters at Beverly, and worked vigorously for the consummation of his treasonable designs. There he was joined by his wife and infant son. He at once communicated, in his disguised writing and commercial phraseology, under the signature of Gustavus, his plan to Sir Henry Clinton, through Major André, whom he addressed as "John Anderson." That plan we have already alluded to. Sir Henry was delighted with it, and eagerly sought to carry it out. He was not yet fully aware of the real character behind "Gustavus," although for several months he had suspected it to be General Arnold. Unwilling to proceed further upon uncertainties, he proposed sending an officer to some point near the American lines, who should have a personal interview with his correspondent. "Gustavus" consented, stipulating, however, that the messenger from Clinton should be Major Andre, his adjutant-general.

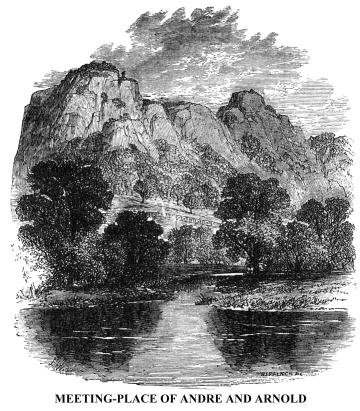

Arnold and André agreed to meet at Dobbs's Ferry, twenty-two miles above New York, upon what was then known as neutral ground. The British water-guard prevented the approach of Arnold. Sir Henry, anxious to complete the arrangement, and to execute the plan, sent the Vulture sloop of war up the river as far as Tarry Town, with Colonel Robinson, the owner of Beverly, who managed to communicate with Arnold. A meeting of Arnold and André was arranged. On the morning of the 20th of August, the latter officer left New York, proceeded by land to Dobbs's Ferry, and from thence to the Vulture, where it was expected the traitor would meet him that night. The wily general avoided the great danger. He repaired to the house of Joshua Hett Smith, a brother to the Tory chief justice of New York, and employed him to go to the Vulture at night, and bring a gentleman to the western shore of the Hudson.

There

was delay, and Smith did not make the voyage until the night of the 21st,

after the moon had gone behind the high hills in the west. With muffled oars

he paddled noiselessly out of Haverstraw Creek, and, at little past midnight,

reached the Vulture. It was a serene night, not a ripple was upon the bosom

of the river. Not a word was spoken. The boat came alongside, with a concerted

signal, and received Sir Henry's representative. André was dressed

in his scarlet uniform, but all was concealed by a long blue surtout, buttoned

to the chin. He was conveyed to an estuary at the foot of Long Clove Mountain,

a little below the Village of Haverstraw. Smith led the officer to a thicket

near the shore, and then, in a low whisper, introduced "John Anderson"

to "Gustavus," who acknowledged himself to be Major-General Arnold,

of the Continental Army. There, in the deep shadows of night, concealed from

human cognizance, with no witnesses but the stars above them, they discussed

the dark plans of treason, and plotted the utter ruin of the Republican cause.

The faint harbingers of day began to appear in the east, and yet the conference

was earnest and unfinished. Smith came and urged the necessity of haste to

prevent discovery. Much was yet to be done. Arnold had expected a protracted

interview, and had brought two horses with him. While the morning twilight

was yet dim, they mounted and started for Smith's house. They had not proceeded

far when the voice of a sentinel challenged them, and André found himself

entering the American lines. He paused, for within them he would be a spy.

Arnold assured him by promises of safety; and before sunrise they were at

Smith's house, on what has since been known as Treason Hill. At that moment

the sound of a cannon came booming over Haverstraw Bay from the eastern shore;

and within twenty minutes the Vulture was seen dropping down the river, to

avoid the shots of an American gun on Teller's Point. To the amazement of

André she disappeared. Deep inquietude stirred his spirit. He was within

the American lines, without flag or pass. If detected, he would be called

a spy--a name which he despised as much as that of traitor.

There

was delay, and Smith did not make the voyage until the night of the 21st,

after the moon had gone behind the high hills in the west. With muffled oars

he paddled noiselessly out of Haverstraw Creek, and, at little past midnight,

reached the Vulture. It was a serene night, not a ripple was upon the bosom

of the river. Not a word was spoken. The boat came alongside, with a concerted

signal, and received Sir Henry's representative. André was dressed

in his scarlet uniform, but all was concealed by a long blue surtout, buttoned

to the chin. He was conveyed to an estuary at the foot of Long Clove Mountain,

a little below the Village of Haverstraw. Smith led the officer to a thicket

near the shore, and then, in a low whisper, introduced "John Anderson"

to "Gustavus," who acknowledged himself to be Major-General Arnold,

of the Continental Army. There, in the deep shadows of night, concealed from

human cognizance, with no witnesses but the stars above them, they discussed

the dark plans of treason, and plotted the utter ruin of the Republican cause.

The faint harbingers of day began to appear in the east, and yet the conference

was earnest and unfinished. Smith came and urged the necessity of haste to

prevent discovery. Much was yet to be done. Arnold had expected a protracted

interview, and had brought two horses with him. While the morning twilight

was yet dim, they mounted and started for Smith's house. They had not proceeded

far when the voice of a sentinel challenged them, and André found himself

entering the American lines. He paused, for within them he would be a spy.

Arnold assured him by promises of safety; and before sunrise they were at

Smith's house, on what has since been known as Treason Hill. At that moment

the sound of a cannon came booming over Haverstraw Bay from the eastern shore;

and within twenty minutes the Vulture was seen dropping down the river, to

avoid the shots of an American gun on Teller's Point. To the amazement of

André she disappeared. Deep inquietude stirred his spirit. He was within

the American lines, without flag or pass. If detected, he would be called

a spy--a name which he despised as much as that of traitor.

At noon the whole plan was arranged. Arnold placed in André's possession several papers--fatal papers!--explanatory of the condition of West Point and its dependencies. Zealous for the interests of his king and country, André, contrary to the explicit orders of Sir Henry Clinton, received them. He placed them in his stockings, under his feet, at the suggestion of Arnold, received a pass from the traitor in the event of his being compelled to return to New York by land, and waited with great impatience for the approaching night, when he should be taken in a boat to the Vulture. The remainder of the sad narrative will be repeated presently at a more appropriate point in our journey towards the sea.

Returning from this historical digression, I will recur to the narrative of the events of a winter's day on the Hudson, only to say, that after sketching the Lighthouse and Fog-bell structure upon Stony Point, I hastened to the river, resumed my skates, and at twilight arrived at Peek's Kill, in time to take the railway-car for home. I had experienced a tedious but interesting day. The remembrance of it is far more delightful than was its endurance.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.