CHAPTER XVI.

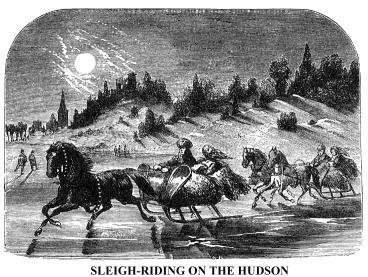

HE winter was mild and constant. No special severity

marked its dealings, yet it made no deviations in that respect from the usual

course of the season sufficient to mark it as an innovator. Its breath chilled

the waters early, and for several weeks the Hudson was bridged with strong

ice, from the wilderness almost to the sea. Meanwhile the whole country was

covered with a thick mantle of snow. Skaters, ice-boats, and sleighs traversed

the smooth surface of the river with perfect safety, as far down as Peek's

Kill Bay, and the counties upon its borders, separated by its flood in summer,

were joined by the solid ice, that offered a medium for pleasant intercourse

during the short and dreary days of winter.

Valentine's Day came--the day in England traditionally associated with the wooing of birds and lovers, and when the crocus and the daffodil proclaim the approach of spring. But here the birds and the early flowers were unseen; the scepter of the frost king was yet all-potent. The blue bird, the robin, and the swallow, our earliest feathered visitors from the south, yet lingered in their southern homes. Soon the clouds gathered and came down in warm and gentle rain; the deep snows of northern New York melted rapidly, and the Upper Hudson and the Mohawk poured out a mighty flood that spread over the valleys, submerged town wharves, and burst the ribs of ice yet thick and compact. Down came the turbid waters whose attrition below, working with the warm sun above, loosened the icy chains that for seventy days had held the Hudson in bondage, and towards the close of February great masses of the shivered fetters were moving with the ebb and flow of the tide. The snow disappeared, the buds swelled, and, to the delight of all, one beautiful morning, when even the dew was not congealed, the blue birds, first harbingers of approaching summer, were heard gaily singing in the trees and hedges. It was a welcome and delightful invitation to the fields and waters, and I hastened to the lower borders of the Highland region to resume my pen and pencil sketches of the Hudson from the wilderness to the sea.

The

air was as balmy as May on the evening of my arrival at Sing Sing, on the

eastern bank of the Hudson, where the State of New York has a large penitentiary

for men and women. I strolled up the steep and winding street to the heart

of the village, and took lodgings for the night. The sun was yet two hours

above the horizon. I went out immediately upon a short tour of observation,

and found ample compensation for the toil occasioned by the hilly pathways

traversed.

The

air was as balmy as May on the evening of my arrival at Sing Sing, on the

eastern bank of the Hudson, where the State of New York has a large penitentiary

for men and women. I strolled up the steep and winding street to the heart

of the village, and took lodgings for the night. The sun was yet two hours

above the horizon. I went out immediately upon a short tour of observation,

and found ample compensation for the toil occasioned by the hilly pathways

traversed.

Sing Sing is a very pleasant village, of almost four thousand

inhabitants. It lies upon a rudely broken slope of hills, that rise about

one hundred and eighty feet above the river, and overlook Tappan Bay,* or

Tappaanse Zee, as the early Dutch settlers called an expansion of the Hudson,

extending  from

Teller's or Croton Point on the north, to the northern bluff of the Palisades

near Piermont. The origin of the name is to be found in the word Sint-sinck,

the title of a powerful clan of the Mohegan or river Indians, who called this

spot Os-sin-ing, from ossin, a stone, and ing, a place--stony

place. A very appropriate name. The land in this vicinity, first parted with

by the Indians, was granted to Frederick Philipse (who owned a large manorial

estate along the Hudson), in 1685.

from

Teller's or Croton Point on the north, to the northern bluff of the Palisades

near Piermont. The origin of the name is to be found in the word Sint-sinck,

the title of a powerful clan of the Mohegan or river Indians, who called this

spot Os-sin-ing, from ossin, a stone, and ing, a place--stony

place. A very appropriate name. The land in this vicinity, first parted with

by the Indians, was granted to Frederick Philipse (who owned a large manorial

estate along the Hudson), in 1685.

* Tap-pan was the name of a Mohegan tribe that inhabited the eastern shores of the bay.

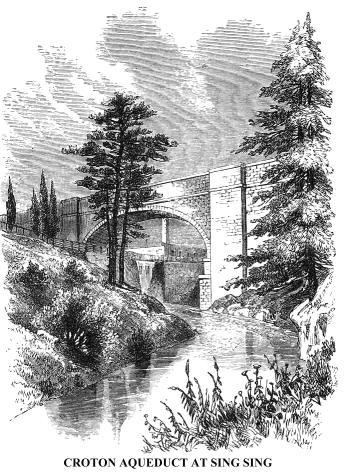

Passing through the upper portion of the village of Sing Sing is a wild, picturesque ravine, lined with evergreen trees, with sides so rugged that the works of man have only here and there found lodgment. Through it flows the Kill, as the Dutch called it, or Sint-sinck brook, which rises among the hills east of the village, and falls into the Hudson after a succession of pretty rapids and cascades. Over it the waters of the Croton river pass on their way to supply the city of New York with a healthful beverage. Their channel is of heavy masonry, here lying upon an elliptical arch of hewn granite, of eighty-eight feet span, its keystone more than seventy feet from the waters of the brook under it. This great aqueduct will be more fully considered presently.

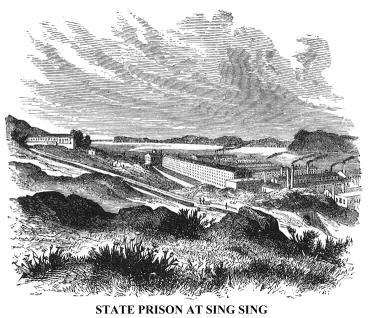

On the southern borders of the village of Sing Sing is a rough group of small hills, called collectively Mount Pleasant. They are formed of dolomite, or white coarse-grained marble, of excellent quality and almost inexhaustible quantity, cropping out from a thin soil in many places. At the foot of Mount Pleasant, on the shore of the river, is a large prison for men, with a number of workshops and other buildings, belonging to the State of New York. A little way up the slope is the prison for women, a very neat and substantial building, with a fine colonnade on the river front. These prisons were built by convicts about thirty years ago, when there were two establishments of the kind in the State, one in the city of New York, the other at Auburn, in the interior. A new system of prison discipline had been adopted. Instead of the old system of indolent, solitary confinement, the workhouse feature was combined with incarceration in separate cells at night. They were made to work diligently all day, but in perfect silence, no recognition by word, look, or gesture, being allowed among them. The adoption of this system, in 1823, rendered the prison accommodation insufficient, and a new establishment was authorized in 1824. Mount Pleasant, near Sing Sing, was purchased, and in May, 1826, Captain Lynds, a farm agent of the Auburn prison, proceeded with one hundred felons from that establishment to erect the new penitentiary. They quarried and wrought diligently among the marble rocks at Mount Pleasant, and the prison for men was completed in 1829, when the convicts in the old State prison in the city of New York were removed to it. It had eight hundred cells, but these were found to be too few, and in 1831 another story was added to the building, and with it two hundred more cells, making one thousand in all, the present number. More are needed, for the number of convicts in the men's prison, at the beginning of 1861, was a little more than thirteen hundred. In the prison for women there were only one hundred cells, while the number of convicts was one hundred and fifty at that time.

The

ground occupied by the prisons is about ten feet above high-water mark. The

main building, in which are the cells, is four hundred and eighty feet in

length, forty-four feet in width, and five stories in height. Between the

outside walls and the cells there is a space of about twelve feet, open from

floor to roof. A part of it is occupied by a series of galleries, there being

a row of one hundred cells to each story on both fronts, and backing each

other. Between the prison and the river are the several workshops, in which

various trades are carried on. In front of the prison for women is the guard-house,

where arms and instructions are given out to thirty-one guardsmen every morning.

Between the guard-house and the prison the Hudson River Railway passes, partly

through two tunnels and a deep trench. Upon the highest points of Mount Pleasant

are guard-houses, which overlook the quarries and other places of industrial

operations.

The

ground occupied by the prisons is about ten feet above high-water mark. The

main building, in which are the cells, is four hundred and eighty feet in

length, forty-four feet in width, and five stories in height. Between the

outside walls and the cells there is a space of about twelve feet, open from

floor to roof. A part of it is occupied by a series of galleries, there being

a row of one hundred cells to each story on both fronts, and backing each

other. Between the prison and the river are the several workshops, in which

various trades are carried on. In front of the prison for women is the guard-house,

where arms and instructions are given out to thirty-one guardsmen every morning.

Between the guard-house and the prison the Hudson River Railway passes, partly

through two tunnels and a deep trench. Upon the highest points of Mount Pleasant

are guard-houses, which overlook the quarries and other places of industrial

operations.

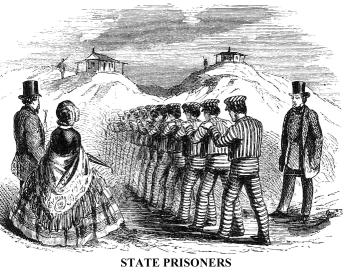

It was just at sunset when I finished my sketch if the prisons

and workshops. A large portion of  Tappan

Bay, and the range of high hills upon its western shore, were then immersed

in a thin purple mist, so frequently seen in this region on balmy afternoons

in the spring and autumn. The prison bell rang as I was turning to leave the

scene, and soon a troop of convicts, dressed in the felon's garb, and accompanied

by overseers, was marched towards the prison and taken to their cells, there

to be fed and locked up for the night. Their costume consists of a short coat,

vest, pantaloons, and cap, made of white kerseymere cloth, broadly striped

with black. The stripes pass around the arms and legs, but are perpendicular

upon the body of the coat.

Tappan

Bay, and the range of high hills upon its western shore, were then immersed

in a thin purple mist, so frequently seen in this region on balmy afternoons

in the spring and autumn. The prison bell rang as I was turning to leave the

scene, and soon a troop of convicts, dressed in the felon's garb, and accompanied

by overseers, was marched towards the prison and taken to their cells, there

to be fed and locked up for the night. Their costume consists of a short coat,

vest, pantaloons, and cap, made of white kerseymere cloth, broadly striped

with black. The stripes pass around the arms and legs, but are perpendicular

upon the body of the coat.

I visited the prisons early the following morning, in company with one of the officers. We first went through that in which the women are kept, and I was surprised at the absence of aspects of crime in the appearance of most of the convicts. The cells were all open, and many of them displayed evidences of taste and sentiment, hardly to be suspected in criminals. Fancy needlework, cheap pictures, and other ornaments, gave some of the cells an appearance of comfort; but the wretchedly narrow spaces into which, in several instances, two of the convicts are placed together at night, because of a want of more cells, dispelled the temporary illusion that prison life was not so very uncomfortable after all. The household drudgery and cookery were performed by the convicts, chiefly by the coloured ones, and a large number were employed in binding hats that are manufactured in the men's prison. They sat in a series of rows, under the eyes of female overseers, silent, yet not very sad. Most of them were young, many of them interesting and innocent in their appearance, and two or three really beautiful. The crime of a majority of them was grand larceny.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.