CHAPTER XX.

HE Harlem River (called Mus-coo-ta by the Indians),

which extends from Kingsbridge to the strait between Long Island Sound and

New York Bay, known as the East River, has an average width of nine hundred

feet. In most places it is bordered by narrow marshy flats, with high hills

immediately behind. The scenery along its whole length, to the villages of

Harlem and Mott Haven, is picturesque. The roads on both shores afford pleasant

drives, and fine country seats and ornamental pleasure-grounds, add to the

landscape beauties of the river. A line of small steamboats, connecting with

the city, traverse its waters, the head of navigation being a few yards above

Post's Century House. The tourist will find much pleasure in a voyage from

the city through the East and Harlem Rivers.

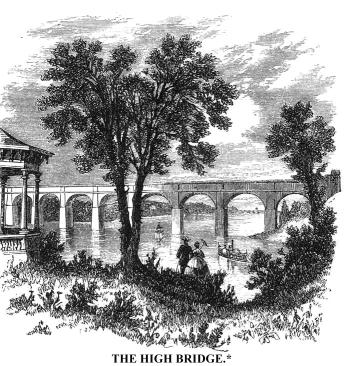

The "High Bridge," or aqueduct over which the waters of the Croton flow from the main land to Manhattan Island, crosses the Island at One Hundred and Seventy-Third Street. It is built of granite. The aqueduct is fourteen hundred and fifty feet in length, and rests upon arches supported by fourteen piers of heavy masonry. Eight of these arches are eighty feet span, and six of them fifty feet. The height of the bridge, above tide water, is one hundred and fourteen feet. The structure originally cost about a million of dollars. Pleasant roads on both sides of the Harlem lead to the High Bridge, where full entertainment for man and horse may be had. The "High Bridge" is a place of great resort in pleasant weather for those who love the road and rural scenery.

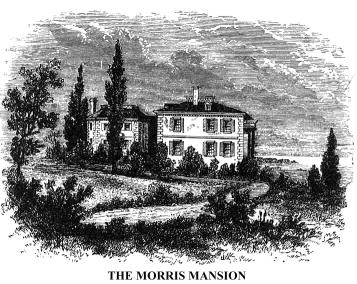

A broad, macadamized avenue, called the "Kingsbridge Road," leads from the upper end of York Island to Manhattanville, where it connects with and is continued by the "Bloomingdale Road," in the direction of the city. The drive over this road is very agreeable. The winding avenue passes through a narrow valley, part of the way between rugged hills, only partially divested of the forest, and ascends to the south-eastern slope of Mount Washington (the highest land on the island), on which stands the village of Carmansville. At the upper end of this village, on the high rocky bank of the Harlem River, is a fine old mansion, known

* This view is from the grounds in front of the dwelling of Richard Carman, Esq., former proprietor of all the land whereon the village of Carmansville stands. He is still owner of a very large estate in that vicinity.

as

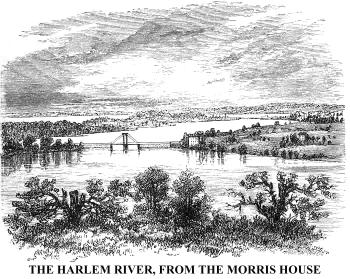

the "Morris House," the residence, until her death in 1865, of the

widow of Aaron Burr, vice-president of the United States, but better known

as Madame Jumel, the name of her first husband. The mansion is at One Hundred

and Sixty-ninth Street. It is surrounded by highly ornamented grounds, and

its situation is one of the most desirable on the island. It commands a fine

view of the Harlem River at the High Bridge, to the village of Harlem and

beyond,*

as

the "Morris House," the residence, until her death in 1865, of the

widow of Aaron Burr, vice-president of the United States, but better known

as Madame Jumel, the name of her first husband. The mansion is at One Hundred

and Sixty-ninth Street. It is surrounded by highly ornamented grounds, and

its situation is one of the most desirable on the island. It commands a fine

view of the Harlem River at the High Bridge, to the village of Harlem and

beyond,*

* Harlem, situated on the Harlem River, between the Eighth Avenue and East River, was an early settlement on the island of Manhattan, by the Dutch. It was a flourishing village, chiefly bordering the Third Avenue, but is now a part of the great metropolis.

also of Long Island Sound, the villages of Astoria and Flushing,

and the green fields of Long Island. Nearer are seen Harlem Plains, and the

fine new bridge at Macomb's Dam. This house was built before the old war for

independence, by Roger Morris, a fellow-soldier with Washington on the  field

of Monongohela, where Braddock fell, in the summer of 1755. Morris was also

Washington's rival in a suit for the heart and hand of Mary, the heir of the

lord of Philipse's Manor. The biographer says that in February, 1756, Colonel

Washington went to Boston to confer with Governor Shirley about military affairs

in Virginia. He stopped in New York on his return, and was then the guest

of Beverly Robinson. Mrs. Robinson's sister, Mary Philipse, was also a guest

there, in the summer-time. Her bright eyes, blooming checks, great vivacity,

perfection of person, aristocratic connections, and prospective wealth, captivated

the young Virginia soldier. He lingered in her presence as

field

of Monongohela, where Braddock fell, in the summer of 1755. Morris was also

Washington's rival in a suit for the heart and hand of Mary, the heir of the

lord of Philipse's Manor. The biographer says that in February, 1756, Colonel

Washington went to Boston to confer with Governor Shirley about military affairs

in Virginia. He stopped in New York on his return, and was then the guest

of Beverly Robinson. Mrs. Robinson's sister, Mary Philipse, was also a guest

there, in the summer-time. Her bright eyes, blooming checks, great vivacity,

perfection of person, aristocratic connections, and prospective wealth, captivated

the young Virginia soldier. He lingered in her presence as  long

as duty would permit, and would gladly have carried her with him to Virginia

as his bridge; but his extreme diffidence kept the momentous question unspoken,

and Roger Morris, his fellow aide-de-camp in Braddock's military family, bore

off the prize. Morris, like his brother-in-law, Beverly Robinson, adhered

to the crown after the American colonies declared themselves independent in

1776. When, in the autumn of that year, the American army under Washington

encamped upon Harlem Heights, and occupied Fort Washington near, Morris fled

for safety to Robinson's house in the Highlands, and Washington occupied his

elegant mansion as his head-quarters for a while. The house is preserved in

its original form and materials, excepting where external repairs have been

necessary.

long

as duty would permit, and would gladly have carried her with him to Virginia

as his bridge; but his extreme diffidence kept the momentous question unspoken,

and Roger Morris, his fellow aide-de-camp in Braddock's military family, bore

off the prize. Morris, like his brother-in-law, Beverly Robinson, adhered

to the crown after the American colonies declared themselves independent in

1776. When, in the autumn of that year, the American army under Washington

encamped upon Harlem Heights, and occupied Fort Washington near, Morris fled

for safety to Robinson's house in the Highlands, and Washington occupied his

elegant mansion as his head-quarters for a while. The house is preserved in

its original form and materials, excepting where external repairs have been

necessary.

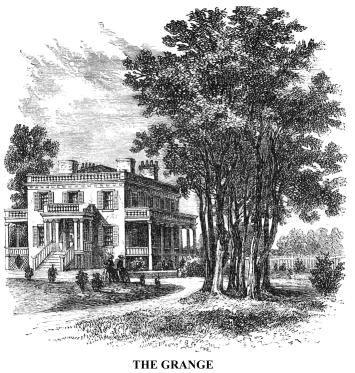

At the lower extremity of Carmansville, and about a mile above

Manhattanville, is a most beautiful  domain,

as yet almost untouched by the hand of change. It is about eight miles from

the heart of the city, completely embowered, and presenting a pleasing picture

at every point of view. This was the home of General Alexander Hamilton, one

of the founders of the Republic, and is one of the few "undesecrated"

dwelling-places of the men of the last century, to be found on York Island.

Near the centre of the ground stands the house Hamilton built for his home,

and which he named "The Grange," from the residence of his grandfather,

in Ayrshire, Scotland. Then it was completely in the country--now it is surrounded

by the suburban residences of the great city. It is situated about half-way

between the Hudson and Harlem Rivers, and is reached from the Kingsbridge

road by a graveled and shaded walk. Near the house is a group of thirteen

trees, planted by Hamilton himself, the year before he was killed in a duel

by Aaron Burr, and named, respectively, after the original thirteen States

of the Union. All of them are straight, vigorous trees, but one, and that,

tradition says, he chanced to name South Carolina. It is crooked in trunk

and branches, and materially disfigures the group. It well typifies the state

of South Carolina in its past history as represented by its ruling class,

which was composed, to a great extent, of professional politicians, who were

arrogant, narrow, opposed to simple republican institutions, and longing for

an alteration in the fundamental principles of their government so as to have

political power centred in few great land and slave holders. This class was

always crooked, always discontented and turbulent, and finally, in the year

1860, disgraced their State and made its name a by-word for all time, by an

attempt to overthrow the Republic, and establish upon its ruins the despotism

of an irresponsible oligarchy, whose basis should be HUMAN SLAVERY! They kindled

a civil war which cost the nation the lives of almost half a million of men,

and nearly three thousand millions of dollars.

domain,

as yet almost untouched by the hand of change. It is about eight miles from

the heart of the city, completely embowered, and presenting a pleasing picture

at every point of view. This was the home of General Alexander Hamilton, one

of the founders of the Republic, and is one of the few "undesecrated"

dwelling-places of the men of the last century, to be found on York Island.

Near the centre of the ground stands the house Hamilton built for his home,

and which he named "The Grange," from the residence of his grandfather,

in Ayrshire, Scotland. Then it was completely in the country--now it is surrounded

by the suburban residences of the great city. It is situated about half-way

between the Hudson and Harlem Rivers, and is reached from the Kingsbridge

road by a graveled and shaded walk. Near the house is a group of thirteen

trees, planted by Hamilton himself, the year before he was killed in a duel

by Aaron Burr, and named, respectively, after the original thirteen States

of the Union. All of them are straight, vigorous trees, but one, and that,

tradition says, he chanced to name South Carolina. It is crooked in trunk

and branches, and materially disfigures the group. It well typifies the state

of South Carolina in its past history as represented by its ruling class,

which was composed, to a great extent, of professional politicians, who were

arrogant, narrow, opposed to simple republican institutions, and longing for

an alteration in the fundamental principles of their government so as to have

political power centred in few great land and slave holders. This class was

always crooked, always discontented and turbulent, and finally, in the year

1860, disgraced their State and made its name a by-word for all time, by an

attempt to overthrow the Republic, and establish upon its ruins the despotism

of an irresponsible oligarchy, whose basis should be HUMAN SLAVERY! They kindled

a civil war which cost the nation the lives of almost half a million of men,

and nearly three thousand millions of dollars.

The "Grange" is upon an elevation of nearly 200 feet above the rivers, and commands, through vistas, delightful views of Harlem River and Plains, the East River and Long Island, and the fertile fields of Lower Westchester. It is just within the outer lines of the entrenchments thrown up by the Americans in 1776, and is in the midst of the theatre of the stirring events of that year.

We have now fairly entered upon Manhattan Island, in our journeyings from the Wilderness to the Sea, and are rapidly approaching the commercial metropolis of the country, seated upon its southern portion, where the waters of the Hudson, the East, and the Passaic Rivers co-mingle in the magnificent harbour of New York.

This island--purchased by the Dutch of the painted savages, only two centuries and a half ago, for the paltry sum of twenty-four dollars, paid in traffic at a hundred per cent. profit--contains tenfold more wealth, in proportion to its size, than any other on the face of the globe. It is thirteen and a-half miles long, and two and a-half miles wide at its greatest breadth. It was originally very rough and rocky, abounding in swamps and conical hills, alternating with fertile spots.

Over the upper part of the island are many pleasant roads not yet straightened into rectangular streets, and these afford fine recreative drives for the citizens, and stirring scenes when the lovers of fast horses, who abound in the city, are abroad. The latter are seen in great numbers in these thoroughfares every pleasant afternoon, when "Young America" takes an airing.

Before making excursions over these ways, and observing their surroundings, let us turn aside from the Kingsbridge Road, in the direction of the Hudson, and, following a winding avenue, note some of the private rural residences that cover the crown and slopes of old Mount Washington, now called Washington Heights. The villas are remarkable for the taste displayed in their architecture, their commanding locations, and the beauty of the surrounding grounds derived from the mingled labour of art and nature. As we approach the river the hills become steeper, the road more sinuous, the grounds more wooded, and the general scenery on land and water more picturesque. One of the most charming of these landscapes, looking in any direction, may be found upon the road just above the Washington Heights railway station, near the delightful residence of Thomas Ingraham, Esq. It our little sketch we are looking up the road, and the slopes of the beautiful lawn in front of his house. Turning half round, we have glimpses of the Hudson, and quite extended views of the bold scenery about Fort Lee, on the opposite shore.

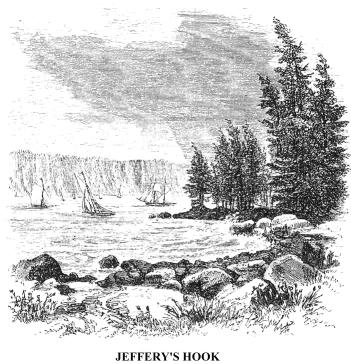

Following

this road a few rods farther down the heights, we reach the station-house

of the Hudson River Railway, which stands at the southern entrance to a deep

rock excavation through a point of Mount Washington, known for a hundred years

or more as Jeffrey's Hook. This point has an interesting revolutionary history

in connection with Mount Washington. At the beginning of the war, the great

value, in a strategic point of view, of Manhattan Island, and of the river

itself--in its entire length to Fort Edward--as a dividing line between New

England and the remainder of the colonies, was fully appreciated by the contending

parties. The Americans adopted measures early to secure these, by erecting

fortifications. Mount Washington (so named at that time) was the most elevated

land upon the island, and formidable military works of earth and stone were

soon erected upon its crown and upon the heights in the vicinity from Manhattanville

to Kingsbridge. The principal work was Fort Washington. The citadel was on

the crown of Mount Washington, overlooking the country in every direction,

and comprising within the scope of vision the Hudson from the Highlands to

the harbour of New York. The citadel, with the outworks, covered several acres

between One Hundred and Eighty-first and One Hundred and Eighty-sixth Streets.

Following

this road a few rods farther down the heights, we reach the station-house

of the Hudson River Railway, which stands at the southern entrance to a deep

rock excavation through a point of Mount Washington, known for a hundred years

or more as Jeffrey's Hook. This point has an interesting revolutionary history

in connection with Mount Washington. At the beginning of the war, the great

value, in a strategic point of view, of Manhattan Island, and of the river

itself--in its entire length to Fort Edward--as a dividing line between New

England and the remainder of the colonies, was fully appreciated by the contending

parties. The Americans adopted measures early to secure these, by erecting

fortifications. Mount Washington (so named at that time) was the most elevated

land upon the island, and formidable military works of earth and stone were

soon erected upon its crown and upon the heights in the vicinity from Manhattanville

to Kingsbridge. The principal work was Fort Washington. The citadel was on

the crown of Mount Washington, overlooking the country in every direction,

and comprising within the scope of vision the Hudson from the Highlands to

the harbour of New York. The citadel, with the outworks, covered several acres

between One Hundred and Eighty-first and One Hundred and Eighty-sixth Streets.

On the point of the chief promontory of Mount Washington jutting

into the Hudson, known as  Jeffery's

Hook, a strong redoubt was constructed, as a cover to chevaux-de-frise

and other obstructions placed in the river between that point and Fort Lee,

to prevent the British ships going up the Hudson. The remains of this redoubt,

in the form of grassy mounds covered with small cedars, are prominent upon

the point, as seen in the engraving above. The ruins of Fort Washington, in

similar form, were also very conspicuous until within a few years, and a flag

staff marked the place of the citadel. But the ruthless hand of pride, forgetful

of the past, and of all patriotic allegiance to the most cherished traditions

of American citizens, has leveled the mounds, and removed the flag-staff;

and that spot, consecrated to the memory of valorous deeds and courageous

suffering, must now be sought for in the kitchen-garden or ornamental grounds

of some wealthy citizen, whose choice celery or bed of

Jeffery's

Hook, a strong redoubt was constructed, as a cover to chevaux-de-frise

and other obstructions placed in the river between that point and Fort Lee,

to prevent the British ships going up the Hudson. The remains of this redoubt,

in the form of grassy mounds covered with small cedars, are prominent upon

the point, as seen in the engraving above. The ruins of Fort Washington, in

similar form, were also very conspicuous until within a few years, and a flag

staff marked the place of the citadel. But the ruthless hand of pride, forgetful

of the past, and of all patriotic allegiance to the most cherished traditions

of American citizens, has leveled the mounds, and removed the flag-staff;

and that spot, consecrated to the memory of valorous deeds and courageous

suffering, must now be sought for in the kitchen-garden or ornamental grounds

of some wealthy citizen, whose choice celery or bed of  verbenas

has greater charms than the green sward of a hillock beneath which reposes

the dust of a soldier of the old war for independence!

verbenas

has greater charms than the green sward of a hillock beneath which reposes

the dust of a soldier of the old war for independence!

"Soldiers buried here?" inquires the startled resident. Yes; your villa, your garden, your beautiful lawn, are all spread out over the dust of soldiers, for all over these heights the blood of Americans, Englishmen, and Germans flowed freely in the autumn of 1776, when the fort was taken by the British after one of the hardest struggles of the war. More than two thousand Americans were captured, and soon filled the loathsome prisons and prison-ships of New York.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.