CHAPTER XX, Part TWO.

Near the river-bank, on the south-western slope of Mount Washington, is the New York Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, one of several retreats for the unfortunate, situated upon the Hudson shore of Manhattan Island. It is one of the oldest institutions of the kind in the United States, the act of the Legislature of New York incorporating it being dated on the day (April 15, 1817) when the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb at Hartford, Connecticut, was opened. The illustrious De Witt Clinton was the first president of the association. Its progress was slow for several years, when, in 1831, Mr. Harvey P. Peet was installed executive head of the asylum, as principal: he infused life into the institution immediately. Its affairs were administered by his skilful and energetic hand during more than thirty years, and his services were marked by the most gratifying results. In 1845, the title of President was conferred upon Mr. Peet, and three or four years later he received the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws. He was at the head of instruction and of the family in the institution. Under his guidance many of both sexes, shut out from participation in the intellectual blessings which are vouchsafed to well-developed humanity, were newly created, as it were, and made to experience, in a degree, the sensations of Adam, as described by Milton:--

"Straight towards heaven my wondering eyes I turned,

And gazed a while the sample sky, till raised

By quick instinctive motion, up I sprung,

As thitherward endeavouring, and upright

Stood on my feet; about me round I saw

Hill, dale, and shady woods, and many plains,

And liquid lapse of murmuring streams; by these,

Creatures that lived, and moved, and walked, or flew;

Birds on the branches warbling; all things smiled:

With fragrance and with joy my heart o'er flowed.

Myself I then perused, and limb by limb

Surveyed, and sometimes west, and sometimes ran,

With supple joints, as lively vigour led;

But who I was, or where, or from what cause,

Knew not; to speak I tried, and forthwith spoke:

My tongue obeyed, and readily could name

Whate'er I saw."

The

situation of the Institution for the Deaf and Dumb is a delightful one. The

lot comprises thirty-seven acres of land, between the Kingsbridge Road and

the river, about nine miles from the New York City Hall. The buildings, five

in number, form a quadrangle of two hundred and forty feet front, and more

than three hundred feet in depth; they are upon a terrace one hundred and

twenty-seven feet above the river, and are surrounded by fine old trees, and

shrubbery. The buildings are capable of accommodating four hundred and fifty

pupils, with their teachers and superintendents, and the necessary domestics.

The

situation of the Institution for the Deaf and Dumb is a delightful one. The

lot comprises thirty-seven acres of land, between the Kingsbridge Road and

the river, about nine miles from the New York City Hall. The buildings, five

in number, form a quadrangle of two hundred and forty feet front, and more

than three hundred feet in depth; they are upon a terrace one hundred and

twenty-seven feet above the river, and are surrounded by fine old trees, and

shrubbery. The buildings are capable of accommodating four hundred and fifty

pupils, with their teachers and superintendents, and the necessary domestics.

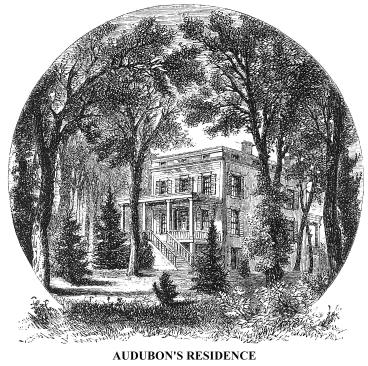

In the midst of a delightful grove of forest trees, a short distance below the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, is the dwelling of the late J.J. Audubon, the eminent naturalist, where some of his family still reside. Only a few years ago it was as secluded as any rural scene fifty miles from the city; now, other dwellings are in the grove, streets have been cut through it, the suburban village of Carmansville has covered the adjacent eminence, and a station of the Hudson River Railway is almost in front of the dwelling.

Audubon was one of the most remarkable men of his age, and his work on the "Birds of America" forms one of the noblest monuments ever made in commemoration of true genius. In that great work, pictures of birds, the natural size, are given in four hundred and eighty-eight plates. It was completed in 1844, and at once commanded the highest admiration of scientific men. Baron Cuvier said of it,--"It is the most gigantic and most magnificent monument that has ever been erected to Nature." Audubon was the son of a French admiral, who settled in Louisiana, and his whole life was devoted to his favourite pursuit. The story of that life is a record of acts of highest heroism, and presents a most remarkable illustration of the triumphs of perseverance.

A writer, who visited Mr. Audubon not long before his death, in 1851, has left the following pleasant account of him and his residence near Mount Washington:--

"My walk soon brought a secluded country house into view,--a house not entirely adapted to the nature of the scenery, yet simple and unpretending in its architecture, and beautifully embowered amid elms and oaks. Several graceful fawns, and a noble elk, were stalking in the shade of the trees, apparently unconscious of the presence of a few dogs, and not caring for the numerous turkeys, geese, and other domestic animals that gobbled and screamed around them. Nor did my own approach startle the wild, beautiful creatures that seemed as docile as any of their tame companions.

"'Is the master at home?' I asked of a pretty maid-servant who answered my tap at the door, and who, after informing me that he was, led me into a room on the west side of the broad hall. It was not, however, a parlour, or an ordinary reception room that I entered, but evidently a room for work. In one corner stood a painter's easel, with a half-finished sketch of a beaver on the paper; on the other lay the skin of an American panther. The antlers of elks hung upon the walls, stuffed birds of every description of gay plumage ornamented the mantelpiece, and exquisite drawings of field-mice, orioles, and woodpeckers, were scattered promiscuously in other parts of the room, across one end of which a long rude table was stretched, to hold artist's materials, scraps of drawing-paper, and immense folio volumes, filled with delicious paintings of birds taken in their native haunts.

"'This,' said I to myself, 'is the studio of the naturalist,' but hardly had the thought escaped me when the master himself made his appearance. He was a tall, thin man, with a high, arched, and serene forehead, and a bright, penetrating, grey eye; his white locks fell in clusters upon his shoulders, but they were the only signs of age, for his form was erect, and his step as light as that of a deer. The expression of his face was sharp, but noble and commanding, and there was something in it, partly derived from the aquiline nose, and partly from the shutting of the mouth, which made you think of the imperial eagle.

"His greeting, as he entered, was at once frank and cordial, and showed you the sincere, true man. 'How kind it is,' he said, with a slight French accent, and in a pensive tone, 'to come to see me, and how wise, too, to leave that crazy city!' He then shook me warmly by the hand. 'Do you know,' he continued, 'how I wonder that men can consent to swelter and fret their lives away amid those hot bricks and pestilent vapours, when the woods and fields are all so near? It would kill me soon to be confined in such a prison-house, and when I am forced to make an occasional visit there, it fills me with loathing and sadness. Ah! how often, when I have been abroad on the mountains, has my heart risen in grateful praise to God that it was not my destiny to waste and pine among those noisome congregations of the city!'"*

* "Homes of American Authors."

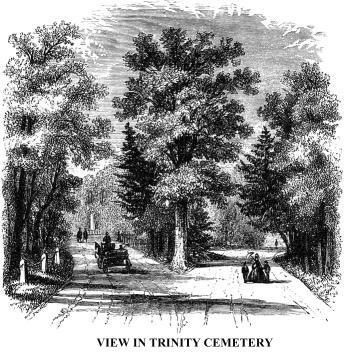

Audubon died at the beginning of 1851, at the age of seventy-one years. His body was laid in a modest tomb in the beautiful Trinity Cemetery, near his dwelling. This burial-place, deeply shaded by original forest trees and varieties that have been planted, affords a most delightful retreat on a warm summer's day. It lies upon the slopes of the river bank. Foot-paths and carriage-roads wind through it in all directions, and pleasant glimpses of the Hudson may be caught through vistas at many points. In the south-western extremity of the grounds, upon a plain granite doorway to a vault, may be seen, in raised letters, the name of Audubon.

The drive from Trinity Cemetery to Manhattanville is a delightful

one. The road is hard and smooth at  all

seasons of the year, and is shaded in summer by many ancient trees that graced

the forest. From it frequent pleasant views of the river may be obtained.

There are some fine residences on both sides of the way, and evidences of

the sure but stealthy approach of the great city are perceptible.

all

seasons of the year, and is shaded in summer by many ancient trees that graced

the forest. From it frequent pleasant views of the river may be obtained.

There are some fine residences on both sides of the way, and evidences of

the sure but stealthy approach of the great city are perceptible.

Manhattanville, situated in the chief of the four valleys that

cleave the island from, the Hudson to the East River, now a pleasant suburban

village, is destined to be soon swallowed by the approaching and rapacious

town. Its site on the Hudson was originally called Harlem Cove. It was considered

a place of strategic importance in the war for independence and the war of

1812, and at both periods fortifications were erected there to command the

pass from the Hudson to Harlem Plains, to whose verge the little village extends.

Upon the heights near, the Roman Catholics  have

two flourishing literary institutions, namely, the Convent of the Sacred Heart,

for girls, and the Academy of the Holy Infant, for boys.

have

two flourishing literary institutions, namely, the Convent of the Sacred Heart,

for girls, and the Academy of the Holy Infant, for boys.

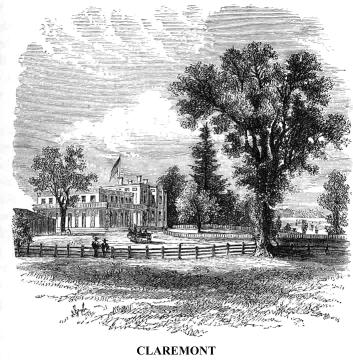

Upon the high promontory overlooking the Hudson, on the south side of Manhattanville, is Jones's Claremont Hotel, a fashionable place of resort for the pleasure-seekers who frequent the Bloomingdale and Kingsbridge roads on pleasant afternoons. At such times it is often thronged with visitors, and presents a lively appearance. The main, or older portion of the building, was erected, I believe, by the elder Dr. Post, early in the present century, as a summer residence, and named by him Claremont. It still belongs to the Post family. It was an elegant country mansion, upon a most desirable spot, overlooking many leagues of the Hudson. There, more than fifty years ago, lived Viscount Courtenay, afterwards Earl of Devon. He left England, it was reported, because of political troubles. When the war of 1812 broke out, he returned thither, leaving his furniture and plate, which were sold at auction. The latter is preserved with care by the family of the purchaser. Courtenay was a great "lion" in New York, for he was a handsome bachelor, with title, fortune, and reputation--a combination of excellences calculated to captivate the heart-desires of the opposite sex.

Claremont was the residence, for awhile, of Joseph Buonaparte,

ex-king of Spain, when he first took  refuge

in the United States, after the battle of Waterloo and the downfall of the

Napoleon dynasty. Here, too, Francis James Jackson, the successor of Mr. Erskine,

the British minister at Washington at the opening of the war of 1812, resided

a short time. He was familiarly known as "Copenhagen Jackson," because

of his then recent participation in measures for the seizure of the Danish

fleet by the British at Copenhagen. He was politically and socially unpopular,

and presented a strong contrast to the polished Courtenay.

refuge

in the United States, after the battle of Waterloo and the downfall of the

Napoleon dynasty. Here, too, Francis James Jackson, the successor of Mr. Erskine,

the British minister at Washington at the opening of the war of 1812, resided

a short time. He was familiarly known as "Copenhagen Jackson," because

of his then recent participation in measures for the seizure of the Danish

fleet by the British at Copenhagen. He was politically and socially unpopular,

and presented a strong contrast to the polished Courtenay.

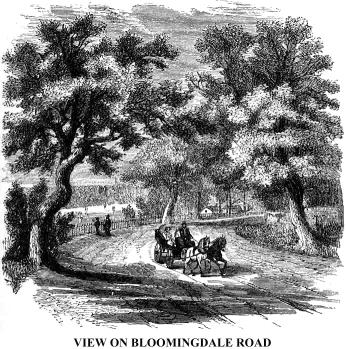

Manhattanville is the northern termination of the celebrated Bloomingdale Road, which crosses the island diagonally from Union Square at Sixteenth Street, to the high bank of the Hudson at One Hundred and Fifteenth Street. It is a continuation of Broadway (the chief retail business street of the city), from Union Square to Harsonville, at Sixty-Eighth Street. In that section it is called Broadway, and is compactly built upon. Beyond Seventieth Street it is still called Bloomingdale Road--a hard, smooth, macadamised highway, broad, devious, and undulating, shaded the greater portion of its length, made attractive by many elegant residences and ornamental grounds, and thronged every fine day with fast horses and light vehicles, bearing the young and the gay of both sexes. The stranger in New York will have the pleasure of his visit greatly enhanced by a drive over this road toward the close of a pleasant day. Its nearest approach to the river is at One Hundred and Fifteenth Street, at which point our little sketch was taken.

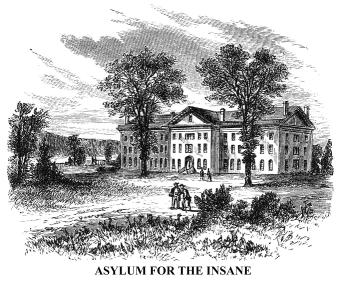

Among

the places of note on the Bloomingdale Road is the New York Asylum for the

Insane, Elm Park, and the New York Orphan Asylum. The former is situated on

the east side of the road where it approaches nearest the Hudson, the grounds,

containing forty acres, occupying the entire square between Tenth and Eleventh

Avenues, and One Hundred and Fifteenth and One Hundred and Twentieth Streets.

The institution was opened in the year 1821, for the reception of patients.

It may be considered a development of the Lunatic Asylum founded in 1810.

Its establishment upon more rational principles is due to the benevolent Thomas

Eddy, a Quaker, who proposed to the governors of the old institution a course

of moral treatment more thorough and extensive than had yet been tried.

Among

the places of note on the Bloomingdale Road is the New York Asylum for the

Insane, Elm Park, and the New York Orphan Asylum. The former is situated on

the east side of the road where it approaches nearest the Hudson, the grounds,

containing forty acres, occupying the entire square between Tenth and Eleventh

Avenues, and One Hundred and Fifteenth and One Hundred and Twentieth Streets.

The institution was opened in the year 1821, for the reception of patients.

It may be considered a development of the Lunatic Asylum founded in 1810.

Its establishment upon more rational principles is due to the benevolent Thomas

Eddy, a Quaker, who proposed to the governors of the old institution a course

of moral treatment more thorough and extensive than had yet been tried.

The place selected for the asylum, near the village of Bloomingdale, is unequalled. The ground is elevated and dry, and affords extensive and delightful views of the Hudson and the adjacent city and country. The buildings are spacious, the grounds beautifully laid out, and ornamented with shrubbery and flowers, and every arrangement is made with a view to soothe and heal the distempers of the mind. The patients are allowed to busy themselves with work or chosen amusements, to walk in the garden or pleasure-grounds, and to ride out on pleasant days, proper discrimination being always observed.

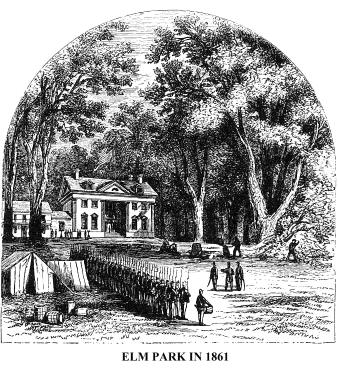

A short distance below the Asylum for the Insane, on the cast

side of the Bloomingdale Road, is the fine  old

country seat of the Apthorpe family, called Elm Park. It is now given to the

uses of mere devotees of pleasure. Here the Germans of the city congregate

in great numbers during hours of leisure, to drink beer, tell stories, smoke,

sing, and enjoy themselves in their peculiar way with a zeal that seems to

be inspired by Moore's idea that--

old

country seat of the Apthorpe family, called Elm Park. It is now given to the

uses of mere devotees of pleasure. Here the Germans of the city congregate

in great numbers during hours of leisure, to drink beer, tell stories, smoke,

sing, and enjoy themselves in their peculiar way with a zeal that seems to

be inspired by Moore's idea that--

"Pleasure's the only noble end,

To which all human powers should tend."

Elm Park was the head-quarters of Sir William Howe, at the

time of the battle on Harlem Plains, in the autumn of 1776. Washington had

occupied it only the day before, and had there waited anxiously and impatiently

for the arrival of the fugitive Americans under General Putnam, who narrowly

escaped capture when the British took possession of the city. The Bloomingdale

Road, along which they moved, then passed through almost  continuous

woods in this vicinity. Washington himself had a very narrow escape here,

for he left the house only a few minutes before the advanced British column

took possession of it.

continuous

woods in this vicinity. Washington himself had a very narrow escape here,

for he left the house only a few minutes before the advanced British column

took possession of it.

Elm Park, when the accompanying sketch was made (June, 1861), was a sort of camp of instruction for volunteers for the army of the Republic, then engaged in crushing the great rebellion, in favour of human slavery and political and social despotism. When I visited it, companies were actively drilling, and the sounds of the fife and drum were mingled with the voices of mirth and conviviality. It was an hour after a tempest had passed by which had prostrated one or two of the old majestic trees which shade the ground and the broad entrance lane. These trees, composed chiefly of elms and locusts, attest the antiquity of the place, and constitute the lingering dignity of a mansion where wealth and social refinement once dispensed the most generous hospitality. Strong are the contrasts in its earlier and later history.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.