CHAPTER XXII.

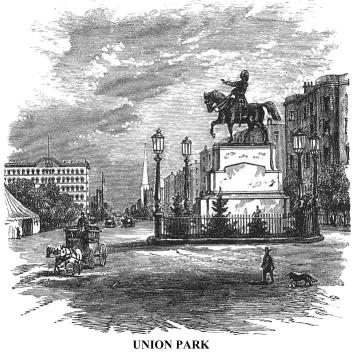

OWN Broadway, a few streets below the Fifth Avenue Hotel,

is Union Park, whose form is an ellipse. It is at the head of Old Broadway,

at Fourteenth Street, and is at such an elevation that the Hudson and East

Rivers may both be seen by a spectator on its Fourteenth Street front. It

is a small enclosure, with a large fountain, and pleasantly shaded with young

trees. Only a few years ago this vicinity was an open common, and where Union

Park is was a high hill. On its northern side is the Everett House, a large,

first-class hotel, named in honour of Edward Everett, the American scholar

and statesman, who represented his country at the Court of St. James's a few

years ago. On its southern side is the Union Park Hotel, and around it are

houses that were first-class a dozen years ago. In one of the four triangles

outside the square is a bronze equestrian statue of Washington, by H.K. Brown,

an American sculptor, standing upon a high granite pedestal, surrounded by

heavy iron railings. This is the only public statue in the city of New York,

if we except a small sandstone one in the City Hall Park, and a marble one

of William Pitt, at the corner of Franklin Street and West Broadway, which

stood at the junction of Wall and William Streets, when the old war for independence

broke out. The latter is only a torso, the head and arms having been broken

off by the British soldiery after Sir William Howe took possession of the

city in the autumn of 1776.* In our little picture we look up the Fourth Avenue,

which extends to Harlem, and from which proceed two great railways, namely,

the Harlem, leading to Albany, and the New Haven, that connects with all the

railways in New England. On the left, by the side of Union Park, is seen a

marquee, the head-quarters of a regiment of Zouave volunteers for the United

States army. These signs of war might then be seen in all parts of the city.

* This broken statue has disappeared since the above was written.

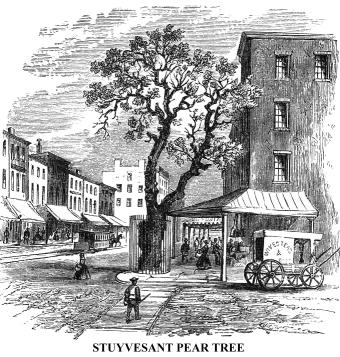

Let

us turn here and ride through broad Fourteenth Street, towards the East River,

passing the Opera House on the way. We are going to visit the oldest living

thing in the city of New York,--an ancient pear tree, at the corner of Thirteenth

Street and Third Avenue. It was brought from Holland by Peter Stuyvesant,

the last and most renowned of the governors of New Motherland (New York) while

it belonged to the Dutch. Stuyvesant brought the tree from Holland, and planted

it in his garden in the year 1647. I believe it was never known to fail in

bearing fruit. Many of the pears have been preserved in liquor as curiosities,

and many a twig has left the parent stem for transplantation in far distant

soil. The tree seems to have vigour enough to last another century.

Let

us turn here and ride through broad Fourteenth Street, towards the East River,

passing the Opera House on the way. We are going to visit the oldest living

thing in the city of New York,--an ancient pear tree, at the corner of Thirteenth

Street and Third Avenue. It was brought from Holland by Peter Stuyvesant,

the last and most renowned of the governors of New Motherland (New York) while

it belonged to the Dutch. Stuyvesant brought the tree from Holland, and planted

it in his garden in the year 1647. I believe it was never known to fail in

bearing fruit. Many of the pears have been preserved in liquor as curiosities,

and many a twig has left the parent stem for transplantation in far distant

soil. The tree seems to have vigour enough to last another century.

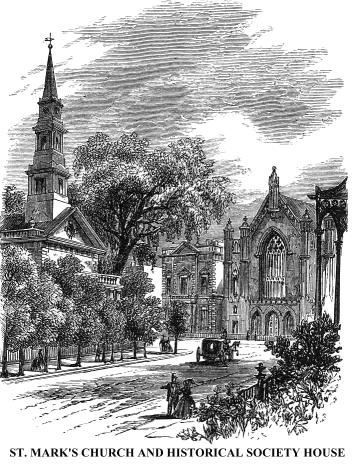

Stuyvesant's dwelling, upon his "Bowerie estate,"

was near the present St. Mark's Church, Tenth Street, and Second Avenue. It

was built of small yellow brick, imported from Holland. To this secluded spot

he retired when he was compelled to surrender the city and province to the English, in 1664. There he lived with his family

for eighteen years, employed in agricultural pursuits. He built a chapel,

at his own cost, on the site of St. Mark's, and in a vault within it he was

buried. The slab of brown freestone that covered it, and which now occupies

a place in the rear wall of St. Mark's, bears the following inscription:--"In

this vault lies Petrus Stuyvesant, late Captain-General and Commander-in-chief

of Amsterdam, in New Netherlands, now called New York, and the Dutch West

India Islands. Died, August, A.D. 1682, aged eighty years."*

the city and province to the English, in 1664. There he lived with his family

for eighteen years, employed in agricultural pursuits. He built a chapel,

at his own cost, on the site of St. Mark's, and in a vault within it he was

buried. The slab of brown freestone that covered it, and which now occupies

a place in the rear wall of St. Mark's, bears the following inscription:--"In

this vault lies Petrus Stuyvesant, late Captain-General and Commander-in-chief

of Amsterdam, in New Netherlands, now called New York, and the Dutch West

India Islands. Died, August, A.D. 1682, aged eighty years."*

St. Mark's Church, seen on the left in our little sketch, now

ranks among the older church edifices in the city. It was built in 1799, and

several of the descendants of Peter Stuyvesant have been, and still are, members

of the congregation. When erected, it was more than a mile  from

the city, in the midst of pleasant country seats. The old Stuyvesant mansion

was yet standing, and the "Bowery Lane" (now the broad street called

the Bowery), and the old Boston Port road, were the nearest highways. Near

it, on the Second Avenue, is seen a Gothic edifice--the Baptist Tabernacle--by

the side of which is a square building of drab freestone, belonging to the

New York Historical Society. The latter is one of the most flourishing and

important associations in New York, and numbers among its membership--resident,

corresponding, and honorary--many of the best minds in America and Europe.

It has a very large and valuable library, and an immense collection of manuscripts

and rare things; also the entire collection of Egyptian antiquities brought

to the United States by the late Dr. Abbott, several marbles from Nineveh,

and a choice gallery of pictures, chiefly by American artists.+

from

the city, in the midst of pleasant country seats. The old Stuyvesant mansion

was yet standing, and the "Bowery Lane" (now the broad street called

the Bowery), and the old Boston Port road, were the nearest highways. Near

it, on the Second Avenue, is seen a Gothic edifice--the Baptist Tabernacle--by

the side of which is a square building of drab freestone, belonging to the

New York Historical Society. The latter is one of the most flourishing and

important associations in New York, and numbers among its membership--resident,

corresponding, and honorary--many of the best minds in America and Europe.

It has a very large and valuable library, and an immense collection of manuscripts

and rare things; also the entire collection of Egyptian antiquities brought

to the United States by the late Dr. Abbott, several marbles from Nineveh,

and a choice gallery of pictures, chiefly by American artists.+

* Peter Stuyvesant was a native of Holland; he was bred to the art of war, and had been in public life, as Governor of Curacoa, before he assumed the government of New Netherlands. He was a man of dignity, honest and true. He was energetic, aristocratic, and overbearing. His deportment made him unpopular with the people, yet his services were vastly more value to them and the province than those of any of his predecessors. He was "Peter the Headstrong" in Knickerbocker's burlesque history of New York, written by Irving, who describes him as a man "of such immense activity and decision of mind, that he never sought nor accepted the advice of others.". . . . . "A tough, sturdy, valiant, weather-beaten, mettlesome, obstinate, leather-sided, lion hearted, generous-spirited old governor."

+ The New York Historical Society was organized in December, 1804. Its fire-proof building, in which its collections are deposited, was completed in the autumn of 1857.

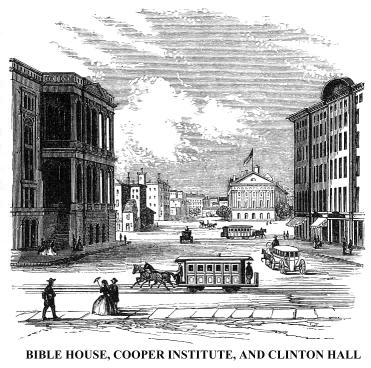

In a cluster, a short distance from St. Mark's, are the Bible

House, Cooper Institute, Clinton Hall,  and

Astor Library,* places which intelligent strangers in the city should not

pass by. The first three are seen in our sketch, the Bible House on the right,

the Cooper Institute on the left, and Clinton Hall in the distance. The open

area is Astor Place.

and

Astor Library,* places which intelligent strangers in the city should not

pass by. The first three are seen in our sketch, the Bible House on the right,

the Cooper Institute on the left, and Clinton Hall in the distance. The open

area is Astor Place.

* The New York Society Library, in University Place, is the oldest public library in the United States. It was incorporated in the year 1700, under the title of "The Public Library of New York." Its name was changed to its present on in 1754. It contains almost 50,000 volumes.

The Bible House occupies a whole block or square. It belongs

to the American Bible Society. A large portion of the building is devoted

to the business of the association. Blank paper is delivered to the presses

in the sixth story, and proceeds downwards through regular stages of manufacture,

until it reaches the  depository

for distribution on the ground floor, in the form of finished books. A large

number of religious and kindred societies have offices in this building.

depository

for distribution on the ground floor, in the form of finished books. A large

number of religious and kindred societies have offices in this building.

The Cooper Institute is the pride of New York, for it is the creation of a single New York merchant, Peter Cooper, Esq. The building, of brown freestone, occupies an entire block or square, and cost over 300,000 dollars. The primary object of the founder is the advancement of science, and knowledge of the useful arts, and to this end all the interior arrangements of the edifice were made. When it was completed, Mr. Cooper formally conveyed the whole property to trustees, to be devoted to the public good.* By his munificence, benevolence, and wisdom displayed in this gift to his countrymen, Mr. Cooper takes rank among the great benefactors of mankind.

* The chief operations of the Institute (which Mr. Cooper calls "The Union") are free instruction of classes in science and the useful arts, and free lectures. The first and second stores are rented, the proceeds of which are devoted to defraying the expenses of the establishment. In the basement is a lecture-room 125 feet by 82 feet, and 21 feet in height. The three upper stories are arranged for purposes of instruction. There is a large hall, with a gallery, designed for a free Public Exchange.

Clinton Hall belongs to the Mercantile Library Association, which is composed chiefly of merchants and merchants' clerks. It has a membership of between four and five thousand persons, and a library of nearly seventy thousand volumes. The building was formerly the Astor Place Opera House, and in the open space around it occurred the memorable riot occasioned by the quarrel between Forrest and Macready, to which allusion has been made.

Near Astor Place, on Lafayette Place, is the Astor Library, created by the munificence of the American Croesus, John Jacob Astor, who bequeathed for the purpose 400,000 dollars. The building (made larger than at first designed, by the liberality of the son of the founder, and chief inheritor of his property) is capable of holding 200,000 volumes. More than half that number are there now. The building occupies a portion of the once celebrated Vauxhall Gardens, a place of amusement thirty years ago.

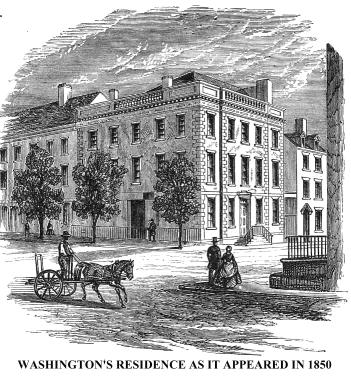

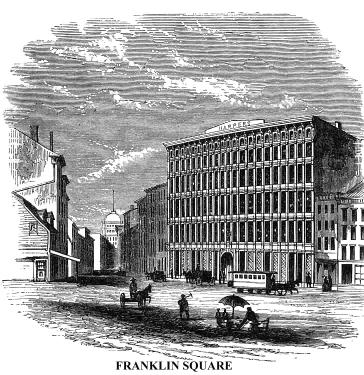

Let us now ride down the Bowery, the broadest street in the

city, and lined almost wholly with small retail shops. It leads us to Franklin Square, a small triangular space at

the junction of Pearl and Cherry Streets. This, in the "olden time,"

was the fashionable quarter of the city, and was remarkable first for the

great Walton House, and a little later as the vicinity of the residence of

Washington during the first year of his administration as first President

of the United States. That building was No. 10, Cherry Street. By the demolition

of some houses between it and Franklin Square, it formed a front on that open

space. In 1856, the Bowery was continued from Chatham Square to Franklin Square,

when this and adjacent buildings were demolished, and larger edifices erected

on their sites. There Washington held his first levees, and there Mr. Hammond,

the first resident minister from England sent to the new Republic, was received

by the chief magistrate of the Republic. The chief attraction to the stranger

at Franklin Square at the present time, is the extensive printing and publishing

house of Harper and Brothers.

retail shops. It leads us to Franklin Square, a small triangular space at

the junction of Pearl and Cherry Streets. This, in the "olden time,"

was the fashionable quarter of the city, and was remarkable first for the

great Walton House, and a little later as the vicinity of the residence of

Washington during the first year of his administration as first President

of the United States. That building was No. 10, Cherry Street. By the demolition

of some houses between it and Franklin Square, it formed a front on that open

space. In 1856, the Bowery was continued from Chatham Square to Franklin Square,

when this and adjacent buildings were demolished, and larger edifices erected

on their sites. There Washington held his first levees, and there Mr. Hammond,

the first resident minister from England sent to the new Republic, was received

by the chief magistrate of the Republic. The chief attraction to the stranger

at Franklin Square at the present time, is the extensive printing and publishing

house of Harper and Brothers.

The Walton House, now essentially changed in appearance, was by far the finest specimen of domestic architecture in the city or its suburbs It stood alone, in the midst of trees and shrubbery, with a beautiful garden covering the slope between it and the East river. It was built by a wealthy ship owner, a brother of Admiral Walton, of the British navy, in pure English style. It attracted great attention. A lately-deceased resident of New York once informed me, that when he was a schoolboy and lived in Wall Street, he was frequently rewarded for good behaviour, by permission to "go out on Saturday afternoon to see Master Walton's grand house." The family arms, carved in wood, remained over the street door until 1850. It was a place of great resort for the British officers during the war for independence; and there William IV., then a midshipman under Admiral Digby, was entertained with the courtesy due to a prince.

On the site of the residence of Walter Franklin, a Quaker and wealthy merchant, whose name the locality commemorates, stand the Harpers' magnificent structures of brick and iron (the front all iron), which soon arose from the ashes of their old establishment, consumed near the close of 1853. There are two buildings, the rear one fronting on Cliff Street. The latter is seven stories in height, and the one on Franklin Square six stories, exclusive of the basements and sub-cellars. Between them is a court, in which is a lofty brick tower, with an interior spiral staircase. From this iron bridges extend to the different stories. The buildings are almost perfectly fire-proof. It is the largest establishment of its kind in the United States. Over six hundred persons are usually employed in it. It was founded nearly fifty years ago, by two of the four brothers who compose the firm. They are all yet (1866) actively engaged in the management of the affairs of the house, with several of their sons, and may be found during business hours, ever ready to extend the hand of cordial welcome to strangers, and to give them the opportunity to see the operation of book-making in all its departments, and in the greatest perfection.

On our way from Franklin Square to the Hudson, by the most direct

route, we cross the City Hall Park, which was known a century ago as "The

Fields." It was then an open common on the northern border of the city,

at "the Forks of the Broadway." It is triangular in form. The great

thoroughfare of Broadway is on its western side, and the City Hall, a spacious

edifice of white marble, stands in its centre. Near its southern end is a

large fountain of Croton water. On its eastern side was a declivity overlooking

"Beekm an's

Swamp." That section of the city is still known as "The Swamp"--the

great leather mart of the metropolis. On the brow of that declivity, where

Tammany Hall now stands, Jacob Leisler, "the people's governor,"

when James II, left the English throne and William of Orange ascended it,

was hanged, having been convicted on the false accusation of being a disloyal

usurper. He was the victim of a jealous and corrupt aristocracy, and was the

first and last man ever put to death for treason alone within the domain of

the United States down to the close of the Civil War in 1865.

an's

Swamp." That section of the city is still known as "The Swamp"--the

great leather mart of the metropolis. On the brow of that declivity, where

Tammany Hall now stands, Jacob Leisler, "the people's governor,"

when James II, left the English throne and William of Orange ascended it,

was hanged, having been convicted on the false accusation of being a disloyal

usurper. He was the victim of a jealous and corrupt aristocracy, and was the

first and last man ever put to death for treason alone within the domain of

the United States down to the close of the Civil War in 1865.

When the war for independence was kindling, the Field became the theatre of many stirring scenes. There the inhabitants assembled to hear the harangues of political leaders and pass resolves: there "liberty poles" were erected and prostrated; and there soldiers and people had collisions. There obnoxious men were hung in effigy; and there at six o'clock in the evening of a sultry day in July, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was read to one of the brigades of the Continental Army, then in the city under the command of Washington.

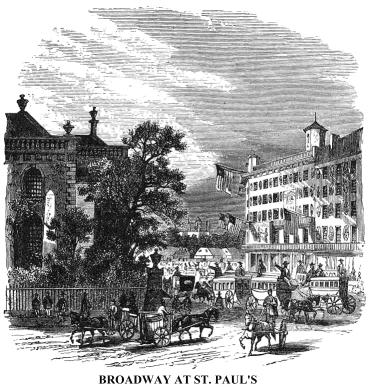

The vicinity of the lower or southern end of the park has ever

been a point of much interest. On the site of Barnum's Museum,* the "Sons of Liberty" in New York--the

ultra-republicans before the revolution--had a meeting-place, called "Hampden

Hall." Opposite was St. Paul's Church, a chapel of Trinity Church; where,

in after years, when the objects for which the "Sons of Liberty"

had been organized were accomplished, namely, the independence of the colonies,

the Te Deum Laudamus was sung by a vast multitude, on the occasion of the

inauguration of Washington (who was present), as the first chief magistrate

of the United States. There it yet stands, on the most crowded portion of

Broadway (where various omnibus lines meet), a venerable relic of the past,

clustered with important and interesting associations. Around it are the graves

of the dead of several generations. Under its great front window is a mural

monument erected to the memory of General Montgomery, who fell at the siege

of Quebec, in 1775: and a few feet from its venerable walls is a marble obelisk,

standing at the grave of Thomas Addis Emmet, brother of, and co-worker with

the eminent Robert Emmet, who perished on the scaffold during the uprising

of the Irish people against the British government, in 1798.

site of Barnum's Museum,* the "Sons of Liberty" in New York--the

ultra-republicans before the revolution--had a meeting-place, called "Hampden

Hall." Opposite was St. Paul's Church, a chapel of Trinity Church; where,

in after years, when the objects for which the "Sons of Liberty"

had been organized were accomplished, namely, the independence of the colonies,

the Te Deum Laudamus was sung by a vast multitude, on the occasion of the

inauguration of Washington (who was present), as the first chief magistrate

of the United States. There it yet stands, on the most crowded portion of

Broadway (where various omnibus lines meet), a venerable relic of the past,

clustered with important and interesting associations. Around it are the graves

of the dead of several generations. Under its great front window is a mural

monument erected to the memory of General Montgomery, who fell at the siege

of Quebec, in 1775: and a few feet from its venerable walls is a marble obelisk,

standing at the grave of Thomas Addis Emmet, brother of, and co-worker with

the eminent Robert Emmet, who perished on the scaffold during the uprising

of the Irish people against the British government, in 1798.

* The Museum building (see opposite St. Paul's in the picture), with all its contents, was destroyed by fire in 1865.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.