CHAPTER XXII, Part TWO.

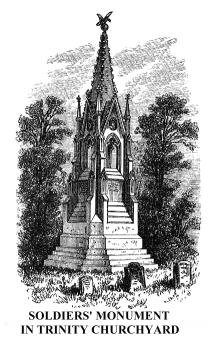

Passing down Broadway, we soon reach Trinity Church, founded at the close of the seventeenth century. The present is the fourth edifice, on the same site. Soon after the British army took possession of New York, in September, 1776, a fire broke out in the lower part of the town. Five hundred edifices were consumed--an eighth of all that were in the city. Trinity Church (the second edifice) was among the number destroyed. It was rebuilt in 1788, and taken down in 1839. The present fine building was then commenced, and was completed in 1843. Within the burial-ground around the church, and the most conspicuous object there, is the magnificent brown freestone monument, erected by order of the vestry, in 1852, and dedicated as "Sacred to the Memory," as an inscription upon it says, "of those brave and good men who died, whilst imprisoned in the city, for their devotion to the cause of American Independence." Hereby is indicated a great change, wrought by time.

When

these "brave and good men" were in prison, one of their most unrelenting

foes was Dr. Inglis, the Rector of Trinity, because they were "devoted

to the cause of American Independence."* The church fronts Wall Street,

the site of the wooden palisades or wall that extended from the Hudson to

the East River, across the island, when it belonged to the Dutch. Here we

enter the ancient domain of New Amsterdam, a city around which the mayor was

required to walk every morning at sunrise, unlock all the gates, and give

the key to the commander of the fort. Such was New York two hundred years

ago.+

When

these "brave and good men" were in prison, one of their most unrelenting

foes was Dr. Inglis, the Rector of Trinity, because they were "devoted

to the cause of American Independence."* The church fronts Wall Street,

the site of the wooden palisades or wall that extended from the Hudson to

the East River, across the island, when it belonged to the Dutch. Here we

enter the ancient domain of New Amsterdam, a city around which the mayor was

required to walk every morning at sunrise, unlock all the gates, and give

the key to the commander of the fort. Such was New York two hundred years

ago.+

* When Washington arrived in New York with troops from Boston, in the spring of 1776, he occupied a house in Pearl Street, near Liberty, not far from Trinity Church. Being a communicant of the Church of England, he attended Divine service there. On Sunday morning, one of Washington's general called on Dr. Inglis, and requested him to omit the violent prayer for the king and royal family. He paid no regard to it. He afterwards said to that officer, "It is in your power to shut up the churches, but you cannot make the clergy depart from their duty." The prisoners alluded to in the inscription on the monuments were those who died in the old Sugar-houses of the city, which were used for hospitals. Many of them were buried in the north part of Trinity Churchyard.

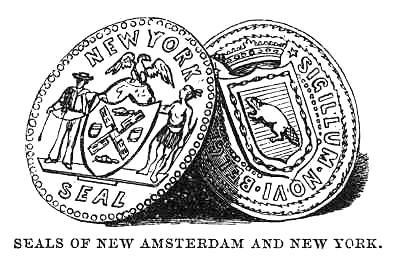

+ The harbour of New York was discovered by Hudson

in September, 1609. It is supposed to have been entered twenty-five years

earlier,

by Verrazani, A florentine. Traders speedily came after the discovery was

proclaimed, and established a trading-house at Albany. In 1613, Captain Block

built a ship near the Bowling Green, to replace the one in which he sailed

from Holland, and which was accidentally burnt. A Dutch West Indian Company

was formed in 1621, with all the elementary powers of government. Their charter

gave them territorial dominion, and the country, called New Netherland, was

made a county of Holland. The seal bore the representation of a beaver rampant,

an animal very valuable for its fur, and then abundant. The seal of the city

of New York, (seen in the engraving) has the beaver in one of its quarterings.

New Amsterdam remained in the possession of the Dutch until 1664, when it

was surrendered into the hands of the English, on demand being made, in the

presence of numerous ships of war, laden with land troops. When the name was

changed from New Amsterdam to New York in honour of James, Duke of York, afterwards

James II., to whom the whole domain had been granted by his profligate brother,

King Charles.

earlier,

by Verrazani, A florentine. Traders speedily came after the discovery was

proclaimed, and established a trading-house at Albany. In 1613, Captain Block

built a ship near the Bowling Green, to replace the one in which he sailed

from Holland, and which was accidentally burnt. A Dutch West Indian Company

was formed in 1621, with all the elementary powers of government. Their charter

gave them territorial dominion, and the country, called New Netherland, was

made a county of Holland. The seal bore the representation of a beaver rampant,

an animal very valuable for its fur, and then abundant. The seal of the city

of New York, (seen in the engraving) has the beaver in one of its quarterings.

New Amsterdam remained in the possession of the Dutch until 1664, when it

was surrendered into the hands of the English, on demand being made, in the

presence of numerous ships of war, laden with land troops. When the name was

changed from New Amsterdam to New York in honour of James, Duke of York, afterwards

James II., to whom the whole domain had been granted by his profligate brother,

King Charles.

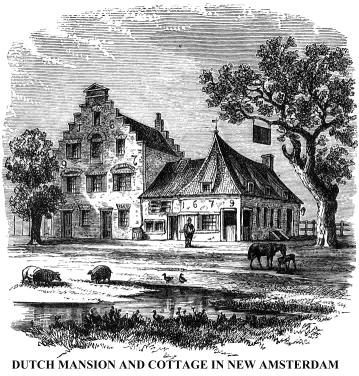

According to early accounts, New Amsterdam must have been a

quaint old town in Stuyvesant's time, at about the middle of the seventeenth

century. It was, in style, a reproduction of a Dutch village of that period,

when modest brick mansions, with terraced gables fronting the street, were

mingled with steep-roofed cottages with dormer windows in sides and gables.

It was then compactly built. The area within the palisades was not large;

settlers in abundance came; and for several years few ventured to dwell remote

from the town, because of the hostile Indians, who swarmed in the surrounding

forests. The toleration that had made Holland an asylum for the oppressed,

was practiced here to its fullest extent. "Do you wish to buy a lot,

build a house, and become a citizen?" was the usual question put to a

stranger. His affirmative answer, with proofs of its sincerity, was a sufficient

passport. They prayed not into private opinion or beli ef;

and bigotry could not take root and flourish in a soil so inimical to its

growth. The inhabitants were industrious, thrifty, simple in manners and living,

hospitable, neighbourly, and honest; and all enjoyed as full a share of human

happiness as a mild despotism would allow, until the interloping "Yankees"

from the Puritan settlements, and the conquering, overbearing English, disturbed

their repose, and made society alarmingly cosmopolitan. This feature increased

with the lapse of time; and now that little Dutch trading village two hundred

years ago--grown into a vast commercial metropolis, and ranking among the

most populous cities of the world--contains representatives of almost every

nation on the face of the earth. Broadway, the famous street of commercial

palaces, terminates at a shaded mall and green, called "The Battery,"

a name derived from fortifications that once existed there. The first fort

erected on Manhattan Island, by the Dutch, was on the banks of the Hudson,

at its mouth, in the rear of Trinity Church. The next was built upon the site

of the Bowling Green, at the foot of Broadway. These were on eminences overlooking

the bay. The latter was

ef;

and bigotry could not take root and flourish in a soil so inimical to its

growth. The inhabitants were industrious, thrifty, simple in manners and living,

hospitable, neighbourly, and honest; and all enjoyed as full a share of human

happiness as a mild despotism would allow, until the interloping "Yankees"

from the Puritan settlements, and the conquering, overbearing English, disturbed

their repose, and made society alarmingly cosmopolitan. This feature increased

with the lapse of time; and now that little Dutch trading village two hundred

years ago--grown into a vast commercial metropolis, and ranking among the

most populous cities of the world--contains representatives of almost every

nation on the face of the earth. Broadway, the famous street of commercial

palaces, terminates at a shaded mall and green, called "The Battery,"

a name derived from fortifications that once existed there. The first fort

erected on Manhattan Island, by the Dutch, was on the banks of the Hudson,

at its mouth, in the rear of Trinity Church. The next was built upon the site

of the Bowling Green, at the foot of Broadway. These were on eminences overlooking

the bay. The latter was  a

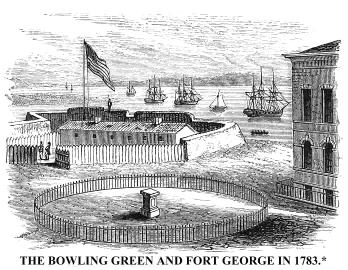

stronger work, and became permanent. It was called Fort Amsterdam: The palisades

on the line of Wall Street (and which suggested its name) were of cedar, and

were planted in 1653, when an English invading force was expected. In 1692,

the English, apprehensive of a French invasion, built a strong battery on

a rocky point at the eastern end of the present Battery, at the foot of White

Hall Street. Finally a stone fort, with four bastions, was erected. It covered

a portion of the ground occupied by the Battery of to-day. It was called Fort

George, in honour of the then reigning sovereign of England. Within its walls

were the governor's house and most of the government offices.

a

stronger work, and became permanent. It was called Fort Amsterdam: The palisades

on the line of Wall Street (and which suggested its name) were of cedar, and

were planted in 1653, when an English invading force was expected. In 1692,

the English, apprehensive of a French invasion, built a strong battery on

a rocky point at the eastern end of the present Battery, at the foot of White

Hall Street. Finally a stone fort, with four bastions, was erected. It covered

a portion of the ground occupied by the Battery of to-day. It was called Fort

George, in honour of the then reigning sovereign of England. Within its walls

were the governor's house and most of the government offices.

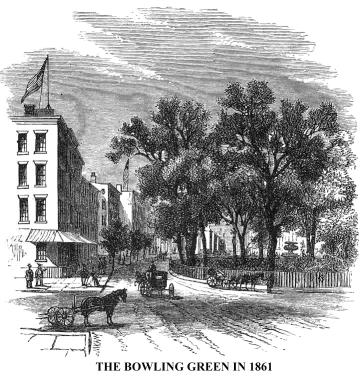

* This little picture shows the appearance of the Bowling Green and its vicinity, soon after the close of the was for independence. Within the enclosure is seen the pedestal on which stood the statue of the king. Near it, the Kennedy House, mentioned in the text, and beyond it, Fort Orange, the Bay of New York, Governor's Island, and the Narrows, on the left, and Staten Island bounding most of the horizon, in the distance.

In the vicinity of the fort many stirring scenes were enacted when the old war for independence was kindling. Hostile demonstrations of the opponents of the famous Stamp Act of 1766 were made there. In front of the fort, Lieutenant-Governor Colden's fine coach, his effigy, and the wooden railing around the Bowling Green, were made materials for a great bonfire by the mob.

At the beginning of the war for independence, Fort George and its, dependencies had three batteries,--one of four guns, near the Bowling Green; another (the Grand Battery) of twenty guns, where the flag-staff on the Battery now stands; and a third of two heavy guns at the foot of White Hall Street, called the White Hall Battery. Here the boldness of the Sons of Liberty was displayed at the opening of the revolution, by the removal of guns from the battery in the face of a cannonade from a British ship of war in the harbour. From here was witnessed, by a vast and jubilant crowd, the final departure of the British army, after the peace of 1783, and the unfurling of the banner of the Republic from the flag-staff of Fort George, over which the British ensign had floated more than six years. The anniversary of that day--"Evacuation Day"--(the 25th of November) is always celebrated in the city of New York by a military parade and feu de joie.

Fort George and its dependencies have long ago disappeared, but the ancient Bowling Green remains. An equestrian statue of George the Third, made of lead, and gilded, was placed upon a high pedestal, in the centre of it, in 1770. It was ordered by the Assembly of the province in 1766, in token of gratitude for the repeal of the odious Stamp Act. The Green was then enclosed with an iron paling.* Only six years later, on the evening when the Declaration of Independence was read to Washington's army in New York, soldiers and citizens joined in pulling down the statue of the king. The round heads of the iron fence-posts were knocked off for the use of the artillery, and the leaden statue of his Majesty was made into bullets for the use of the republican army. "His troops," said a writer of the day, referring to the king, "will probably have melted majesty fired at them." The pedestal of the statue, seen in the engraving, remained in the Bowling Green some time after the war; and the old iron railing, with its decapitated posts, is still there. A fountain of Croton water occupies the site of the statute; and the surrounding disc of green sward, where the citizens amused themselves with bowling, is now shaded by magnificent trees.

* This work of art was by Wilton, of London, and was the first equestrian statue of his Majesty ever erected. Wilton made a curious omission--stirrups were wanting. It was a common remark of the Continental soldiers, that it was proper for "the tyrant" to ride a hard trotting horse without stirrups.

Near the Bowling Green, across Broadway (No. 1), is the Kennedy

[Illustration : THE BOWLING GREEN IN 1861.]

House, where Washington and General Lee, and afterwards Sir Henry Clinton,

Generals Robertson and Carleton, and other British officers, had their head-quarters.

It has been recently altered by an addition to its height.*

* This house was built by Captain Kennedy, of the Royal Navy, at about the time of his marriage with the daughter of Peter Schuyler's, of New Jersey, in 1765.

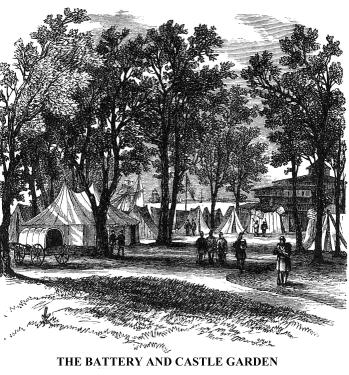

The

present Battery or park, looking out upon the bay of New York, was formed

early in the present century; and a castle, pierced for heavy guns, was erected

near its western extremity. For many years, the Battery was the chief and

fashionable promenade for the citizens in summer weather; and State Street,

along its town border, was a very desirable place of residence. The castle

was dismantled, and became a place of public amusement. For a long time it

was known as Castle Garden; but both are now deserted by fashion and the Muses.

All of old New York has been converted into one vast business mart, and there

are very few respectable residences within a mile of the Battery. At the present

time (September, 1861), it exhibits a martial display. Its green sward is

covered with tents and barracks for the recruits of the Grand National Army

of Volunteers, and its fine old trees give grateful shade to the newly-fledged

soldiers preparing for the war for the Union.

The

present Battery or park, looking out upon the bay of New York, was formed

early in the present century; and a castle, pierced for heavy guns, was erected

near its western extremity. For many years, the Battery was the chief and

fashionable promenade for the citizens in summer weather; and State Street,

along its town border, was a very desirable place of residence. The castle

was dismantled, and became a place of public amusement. For a long time it

was known as Castle Garden; but both are now deserted by fashion and the Muses.

All of old New York has been converted into one vast business mart, and there

are very few respectable residences within a mile of the Battery. At the present

time (September, 1861), it exhibits a martial display. Its green sward is

covered with tents and barracks for the recruits of the Grand National Army

of Volunteers, and its fine old trees give grateful shade to the newly-fledged

soldiers preparing for the war for the Union.

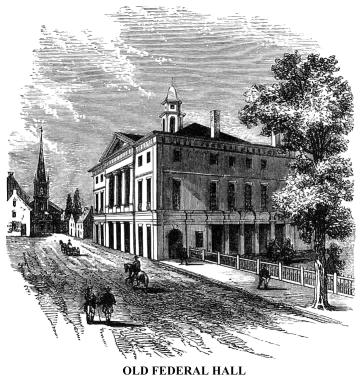

At White Hall, on the eastern border of the Battery, there

was a great civic and military display, at the  close

of April, 1789, when Washington, coming to the seat of government to be inaugurated

first President of the United States, landed there. He was received by officers

and people with shouts of welcome, the strains of martial music, and the roar

of cannon. He was then conducted to his residence on Franklin Square, and

afterwards to the Old Federal Hall in Wall Street, where Congress held its

sessions. It was at the corner of Wall and Nassau Streets, the site on which

a fine marble building was erected for a Custom House, and which is now used

for the purposes of a branch Mint. In the gallery, in front of the hall, the

President took the oath of office, administered by Chancellor Livingston,

in the presence of a great assemblage of people who filled the street.

close

of April, 1789, when Washington, coming to the seat of government to be inaugurated

first President of the United States, landed there. He was received by officers

and people with shouts of welcome, the strains of martial music, and the roar

of cannon. He was then conducted to his residence on Franklin Square, and

afterwards to the Old Federal Hall in Wall Street, where Congress held its

sessions. It was at the corner of Wall and Nassau Streets, the site on which

a fine marble building was erected for a Custom House, and which is now used

for the purposes of a branch Mint. In the gallery, in front of the hall, the

President took the oath of office, administered by Chancellor Livingston,

in the presence of a great assemblage of people who filled the street.

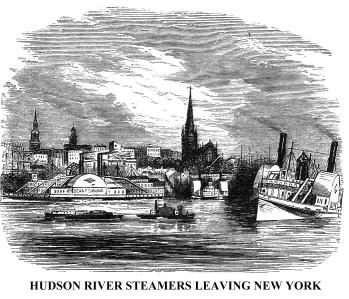

The Hudson from the Battery, northward, is lined with continuous

piers and slips, and exhibits the most animated scenes of commercial life.

The same may be said of the East River for about an equal distance from the

Battery. Huge steam ferry-boats, magnificent passenger  steamers,

and freight barges, ocean steamships, and every variety of sailing vessel

and other water craft may be seen in the Hudson River slips, or out upon the

bosom of the stream, fairly jostling each other near the wharves because of

a lack of room. Upon every deck is seen busy men; and the yo-heave-o! is heard

at the capstan on all sides. But the most animated scene of all is the departure

of steamboats for places on the Hudson, from four to six o'clock each afternoon.

The piers are filled with coaches, drays, carts, barrows, every kind of vehicle

for passengers and light freight. Orange-women and news-boys assail you at

every step with the cries of "Five nice oranges for a shilling!"--"

Ere's the Evening Post and Express, third edition!" whilst the hoarse

voices of escaping waste-steam, and the discordant tintinnabulation of a score

of bells, hurry on the laggards by warnings of the near approach of the hour

of departure. Several bells suddenly cease, when from different slips, steamboats

covered with passengers will shoot out like race-horses from their grooms,

and turning their prows northward, begin the voyage with wonderful speed,

some for the head of tide-water at Troy, others for intermediate towns, and

others still for places so near that the vessels may be ranked as ferry-boats.

The latter are usually of inferior size, but well appointed; and at several

stated hours of the day carry excursionists or country residents to the neighbouring

villages. Let us consider a few of these places, on the western shore of the

Hudson, which the stranger would find pleasant to visit because of the beauty

or grandeur of the natural scenery, and historic associations.

steamers,

and freight barges, ocean steamships, and every variety of sailing vessel

and other water craft may be seen in the Hudson River slips, or out upon the

bosom of the stream, fairly jostling each other near the wharves because of

a lack of room. Upon every deck is seen busy men; and the yo-heave-o! is heard

at the capstan on all sides. But the most animated scene of all is the departure

of steamboats for places on the Hudson, from four to six o'clock each afternoon.

The piers are filled with coaches, drays, carts, barrows, every kind of vehicle

for passengers and light freight. Orange-women and news-boys assail you at

every step with the cries of "Five nice oranges for a shilling!"--"

Ere's the Evening Post and Express, third edition!" whilst the hoarse

voices of escaping waste-steam, and the discordant tintinnabulation of a score

of bells, hurry on the laggards by warnings of the near approach of the hour

of departure. Several bells suddenly cease, when from different slips, steamboats

covered with passengers will shoot out like race-horses from their grooms,

and turning their prows northward, begin the voyage with wonderful speed,

some for the head of tide-water at Troy, others for intermediate towns, and

others still for places so near that the vessels may be ranked as ferry-boats.

The latter are usually of inferior size, but well appointed; and at several

stated hours of the day carry excursionists or country residents to the neighbouring

villages. Let us consider a few of these places, on the western shore of the

Hudson, which the stranger would find pleasant to visit because of the beauty

or grandeur of the natural scenery, and historic associations.

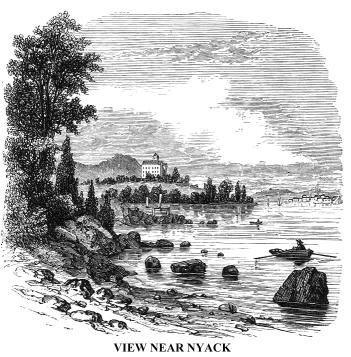

The most remote of the villages to which excursionists go is Nyack, opposite Tarrytown, nearly thirty miles from New York. It lies on the bank of the Hudson at the foot of the Nyack Hills, which are broken ridges, extending several miles northward from the Palisades. Back of the village, and along the river shore, are fertile and well-cultivated slopes, where fruit is raised in abundance. On account of the salubrity of the climate, beautiful and romantic scenery, and good society, it is a very delightful place for a summer residence. From every point of view interesting landscapes meet the eye. The broad Tappan Sea is before it, and stretching along its shores for several miles are seen the towns, and villas, and rich farms of Westchester County. In its immediate vicinity the huntsman and fisherman may enjoy his favourite sport. In its southern suburbs is the spacious building of the Rockland Female Institute, seen in our sketch, in the midst of ten acres of land, and affording accommodation for one hundred pupils. During the ten weeks' summer vacation, it is used as a first-class boarding-house, under the title of the Tappan Zee House.

About four miles below Nyack is Piermont, at which is the terminus

of the middle branch of the New  York

and Erie Railway. The village is the child of that road, and its life depends

mainly upon the sustenance it receives from it. The company has an iron foundry

and extensive repairing shops there; and it is the chief freight depot of

the road. Its name is derived from a pier which juts a mile into the river.

From it freight is transferred to cars and barges. Tappantown, where Major

André was executed, is about two miles from Piermont.

York

and Erie Railway. The village is the child of that road, and its life depends

mainly upon the sustenance it receives from it. The company has an iron foundry

and extensive repairing shops there; and it is the chief freight depot of

the road. Its name is derived from a pier which juts a mile into the river.

From it freight is transferred to cars and barges. Tappantown, where Major

André was executed, is about two miles from Piermont.

A short distance below Piermont is Rockland, a post village of about three hundred inhabitants, pleasantly situated on the river, and flanked by high hills. Here the Palisades proper have their northern termination; and from here to Fort Lee the columnar range is almost unbroken. This place is better known as Sneeden's Landing. Here Cornwallis and six thousand British troops landed, and marched upon Fort Lee, on the top of the Palisades, a few miles below, after the fall of Fort Washington, in the autumn of 1776.

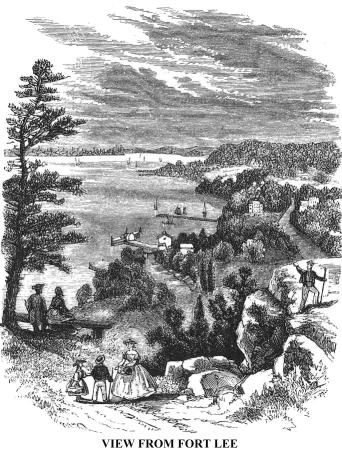

One of the most interesting points on the west shore of the Hudson, near New York, and most resorted to, except Hoboken and its vicinity, is Fort Lee. It is within the domain of New Jersey. The dividing line between that State and New York is a short distance below Rockland or Sneeden's Landing; and it is only the distance between there and its mouth (about twenty miles) that the Hudson washes any soil but that of the State of New York.

The village of Fort Lee is situated at the foot of the Palisades.

A winding road passes from it to the top of the declivity, through a deep,

wooded ravine. The site of the fort is on the left of the head of the ravine,

in the ascent, and is now marked by only a few mounds and a venerable pine-tree

just south of them, which tradition avers once sheltered the tent of Washington.

As the great patriot never pitched his tent there, tradition is in error.

Washington was at the fort a short time at the middle of November, 1776, while

the combined British and Hessian forces were attacking Fort Washington on

the opposite shore. He saw the struggle of the garrison and its assailants,

without ability to aid his friends. When the combat had continued a long time,

he sent word to the commandant of the fort, that if he could hold out until

night, he could bring the garrison off. The assailants were too powerful;

and Washington, with Generals Greene, Mercer, and Putnam, and Thomas Paine,

the  influential

political pamphleteer of the day, was a witness of the slaughter, and saw

the red cross of St. George floating over the lost fortress, instead of the

Union stripes which had been unfurled there a few months before. The title

of Fort Washington was changed to that of Fort Knyphausen, in honour of the

Hessian general who was engaged in its capture. Fort Lee was speedily approached

by the British under Cornwallis, and as speedily abandoned by the Americans.

The latter fled to the Republican camp at Hackensack, when Washington commenced

his famous retreat through New Jersey, from the Hudson to the Delaware, for

the purpose of saving the menaced federal capital, Philadelphia.

influential

political pamphleteer of the day, was a witness of the slaughter, and saw

the red cross of St. George floating over the lost fortress, instead of the

Union stripes which had been unfurled there a few months before. The title

of Fort Washington was changed to that of Fort Knyphausen, in honour of the

Hessian general who was engaged in its capture. Fort Lee was speedily approached

by the British under Cornwallis, and as speedily abandoned by the Americans.

The latter fled to the Republican camp at Hackensack, when Washington commenced

his famous retreat through New Jersey, from the Hudson to the Delaware, for

the purpose of saving the menaced federal capital, Philadelphia.

The view from the high point north of Fort Lee is extensive and interesting, up and down the river. Across are seen the villages of Carmansville and Manhattanville, and fine country seats near; while southward, on the left, the city of New York stretches into the dim distance, with Staten Island and the Narrows still beyond. On the right are the wooded cliffs extending to Hoboken, with the little villages of Pleasant Valley, Bull's Ferry, Weehawk, and Hoboken, along the shore.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.