CHAPTER XXIII.

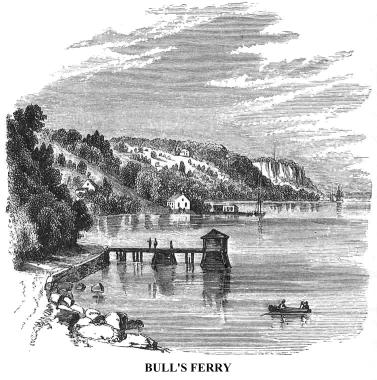

BOUT three miles below Fort Lee is Bull's Ferry, a village of a few

houses, and a great resort for the working-people of New York, when spending

a leisure day. The steep, wooded bank rises abruptly in the rear, to an altitude

of about two hundred feet. There, as at Weehawk, are many pleasant paths through

the woods leading to vistas through which glimpses of the city and adjacent

waters are obtained. Hither pic-nic parties come to spend warm summer days,

where--

"Overhead

The branches arch, and shape a pleasant bower,

Breaking white cloud, blue sky, and sunshine bright,

Into pure ivory and sapphire spots,

And flocks of gold; a soft, cool emerald that

Colours the air, us though the delicate leaves

Emitted self-born light."

Our

little sketch of Bull's Ferry is taken from Weehawk Wharf, and shows the point

on which was a block-house during the revolution; from that circumstance it

has always been called Block-house Point. Its history has a melancholy interest,

as it is connected with that of the unfortunate Major André. In the

summer of 1780, a few weeks before the discovery of Arnold's treason, that

block-house was occupied by a British picket, for the protection of some woodcutters,

and the neighbouring New Jersey loyalists. On Bergen Neck below was a large

number of cattle and horses, belonging to the Americans, within reach of the

foragers who might go out from the British post at Paulus's Hook, now Jersey

City. Washington's head-quarters were then inland, near Ramapo. He sent General

Wayne, with some Pennsylvanian and Maryland troops, horse and foot, to storm

the block-house, and to drive the cattle within the American lines. Wayne

sent the cavalry, under Major Henry Lee, to perform the latter duty, whilst

he and three Pennsylvanian regiments marched against the block-house with

four pieces of cannon. They made a spirited attack, but their cannon were

too light to be effective, and, after a skirmish, the Americans were repulsed

with a loss of sixty men, killed and wounded. After burning some wood-boats

near, and capturing those who had them in charge, Wayne returned to camp with

a large number of cattle driven by the dragoons.

Our

little sketch of Bull's Ferry is taken from Weehawk Wharf, and shows the point

on which was a block-house during the revolution; from that circumstance it

has always been called Block-house Point. Its history has a melancholy interest,

as it is connected with that of the unfortunate Major André. In the

summer of 1780, a few weeks before the discovery of Arnold's treason, that

block-house was occupied by a British picket, for the protection of some woodcutters,

and the neighbouring New Jersey loyalists. On Bergen Neck below was a large

number of cattle and horses, belonging to the Americans, within reach of the

foragers who might go out from the British post at Paulus's Hook, now Jersey

City. Washington's head-quarters were then inland, near Ramapo. He sent General

Wayne, with some Pennsylvanian and Maryland troops, horse and foot, to storm

the block-house, and to drive the cattle within the American lines. Wayne

sent the cavalry, under Major Henry Lee, to perform the latter duty, whilst

he and three Pennsylvanian regiments marched against the block-house with

four pieces of cannon. They made a spirited attack, but their cannon were

too light to be effective, and, after a skirmish, the Americans were repulsed

with a loss of sixty men, killed and wounded. After burning some wood-boats

near, and capturing those who had them in charge, Wayne returned to camp with

a large number of cattle driven by the dragoons.

This event was the theme of a satirical poem, in three cantos, in the ballad style, written by Major André, and published in Rivington's Royal Gazette, in the city of New York. The following is a correct copy, made by the writer for his Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution, in 1850, from an original in the hand-writing of Major André. It was written upon small folio paper. The poem is entitled

THE COW CHASE.

Canto I.

To drive the kine one summer's morn,

The tanner* took his way;

The calf shall rue, that is unborn,

The yumbling of that day.

And Wayne descending steers shall know,

And tauntingly deride,

And call to mind, in every low,

The tanning of his hide.

Yet Bergen cows still ruminate

Unconscious in the stall,

What mighty means were used to get

And lose them after all.

For many heroes bold and brave

From New Bridge and Tapaan,

And those that drink Passale's wave,

And those that eat Soupaan**

And sons of distant Delaware,

And still remoter Shannon,

And Major Lee with horses rare.

And Procter with his cannon.***

All wondrous proud in arms they came--

What hero could refuse,

To tread the rugged path to fame,

Who had a pair of shoes?

At six the heat, with sweating buff,

Arrived at Freedom's Pole,

When Wayne, who thought he'd time enough,

Thus speechified the whole;

'O ye whom glory doth unite,

Who Freedom's cause espouse,

Whether the wing that's doomed to flight,

Or that to drive the cows;

* This is an allusion to the supposed business of General Wayne, in early life, who, it was said, was atanner. He was a surveyor.

** A common name for hasty-pudding, made of the meal of maize or Indian corn.

*** Major Harry Lee was commander of a coprs of light horseman, and Colonel Proctor was at the head of a corps artillery.

"Ere yet you tempt your further way,

Or into action come,

Hear, soldiers, what I have to say,

And take a pint of rust.

"Intemp'rate valour then will string,

Each nervous arm the better,

So all the land shall IO! sing,

And read the gen'ral's letter.

"Know that some paltry refugees,

Whom I've a mind to flight,

Are playing h--l among the trees

That grow on yonder height.

"Their fort and block-house we'll level,

And deal a horrid slaughter;

We'll drive the scoundrels to the devil,

And ravish wife and daughter.

"I under cover of th' attack,

Whilst you are all at blows,

From English Neighb'rhood and Tiwack

Will drive away the cows.

"For well you know the latter is

The serious operation,

And fighting with the refugees

Is only demonstration."

His daring words from all the crowd

Such great applause did gain,

That every man declared aloud

For serious work with Wayne.

Then from the cask of rum once more

They took a heady gill,

When one and all they kindly swore

They'd fight upon the hill.

But here--the muse has not a strain

Befitting such great deeds,

"Hurra," they cried, "hurra for Wayne!"

And, shouting--did their needs.

Canto II.

Near his meridian pomp,

the sun

Had journey'd from the horizon,

When fierce the dusky tribe moved on,

Of heroes drunk as poison.

The sounds confused of boasting oaths,

Re-echoed through the wood,

Some row'd to sleep in dead men's clothes,

And some to swim in blood.

At Irvine's nod,* 'twas fine to see

The left prepared to fight,

The while the drovers, Wayne and Lee,

Drew off upon the right.

Which Irvine 'twas Fame don't relate,

Nor can the Muse assist her,

Whether 'twas he that cocks a hat,

Or he that gives a glister.

For greatly one was signalized,

That fought at Chestnut Hill,

And Canada immortalised

The vendor of the pill.

Yet the attendance upon Procter

They both might have to boast of;

For there was business for the doctor.

And hats to be disposed of.

Let none uncandidly infer

That Stirling wanted spunk,

The self-made peer had sure been there,

But that the peer was drunk.**

But turn we to the Hudson's banks,

Where stood the modest train,

With purpose firm, though slender ranks,

Nor cared a pin for Wayne.

For them the unrelenting hand

Of rebel fury drove,

And tone from ev'ry genial band

Of friendship and of love.

And some within a dangeon's glooms,

By mock tribunals laid,

Had waited long a cruel doom,

Impending o'er their beside.

Here one bewails a brother's fate,

There one a sire demands,

Cut off, alas! before their date,

By Ignominious hands.

And silver'd grandsires here appear'd

In deep distress serene,

Of reversed manners that declared

The better days they'd seen.

Oh! cursed rebellion, these are thine

Thine are these tales of woe;

Shall at thy dire insatiate shrine

Blood never cease to flow?

* General william Irvine, of Pennsylvania.

** William Alexander, who unsuccessfully claimed the title of the Scotch Earl of Stirling. It was believed that his claim was just, and he was generally called "Lord Stirling."

And now the foe began to lead

His forces to th' attack;

Balls whistling unto balls succeed,

And make the block-horse crack.

No shot could pass, if you will take

The gen'ral's word for true;

But 'tis a'd--ble mistake,

For ev'ry shot went through.

The farmer as the rebels pressed,

The loyal heroes stand;

Virtue had nerved each honest breast,

And Industry each hand.

In valour's frenzy, Hamilton

Rode like a soldier big,

And secretary Harrison,

With pen stuck in his wig,*

But, lest chieftain Washington

Should mourn them in the mumps,**

The fate of Withrington to shun,

They fought behind the stumps.

But ah! Thaddeus Posset, why

Should thy poor soul elope?

And why should Titus Hooper die,

Ah! die--without a rope?

Apostate Murphy, thou to whom

Fair Shela ne'er was cruel;

In death should hear her mourn thy down,

Och! would ye die, my jewel?

Thee, Nathan Pumpkin, I lament,

Of melancholy fate,

The gray goose, stolen as he went,

In his heart's blood was west.

Now as the fight was further fought,

And bulls begun to thicken,

The fray assumed, the gen'rals thought,

The colour of a licking.

Yet undismay'd the chiefs command,

And, to redeem the day,

Cry, "Soldiers, charge!" they hear, they stand,

They turn and run away.

Canto III.

Not all delights the

bloody spear,

Or horrid din of battle,

There are, I'm sure, who'd like to hear

A word about the rattle.

* Colonels Hamilton and Harrison, of Washington's staff.

** A painful swelling of the glands, then prevalent in the Republican army.

The chief whom we beheld of late,

Near Schralenberg haranguing,

At Yan Van Poop's unconscious sat

Of Irvine's hearty banging.

While valiant Lee, with courage wild,

Most bravely did oppose

The tears of women and of child,

Who begg'd he'd leave the cows.

But Wayne, of sympathising heart,

Required a relief,

Not all the blessings could impart

Of battle or of beef.

For now a prey to female charms,

His soul took mere delight in

A lovely Hamadryad's arms

Than cow driving or fighting.

A nymph, the refugees had drove

Far from her native tree,

Just happen'd to be on the move,

When up came Wayne and Lee.

She in mad Anthony's fierce eye

The hero saw portray'd,

And, all in tears, she took him by

--The bridle of his jade.

"Hear," said the nymph, "O great

commander,

No human lamentations,

The trees you see them cutting yonder

Are all my near relations.

"And I, forlorn, implore thine aid

To free the sacred grove;

So shall thy prowess be repaid

With an immortal's love."

Now some, to prove she was a goddess:

Said this enchanting fair

Had late retired from the Bodies,*

In all the pomp of war.

That drums and merry fifes had play'd

To honour her retreat,

And Cunningham himself convey'd

The lady through the street.

Great Wayne, by soft compassion sway'd,

To no inquiry stoops,

But takes the fair, afflicted maid

Right into Yan Van Poop's.

* A cant appellation given among the soldiery to the corps that had the honour to guard his majesty's person.

So Roman Anthony, they say,

Disgraced th' imperial banner,

And for a gipsy lost a day,

Like Anthony the tanner.

The Hamadryad had best half

Received redress from Wayne,

When drums and colours, cow and calf,

Came down the road amain.

All in a cloud of dust were seen,

The sheep, the horse, the goat,

The gentle heifer, ass obscene,

The yearling and the shoat.

And pack-horses with fowls came by,

Befeathered on each side,

Like Pegasus, the horse that I,

And other poets ride.

Sublime upon the stirrups rose

The mighty Lee behind,

And drove the terror-smitten cows,

Like chaff before the wind.

But sudden see the woods above

Pour down another corps,

All helter skelter in a drove,

Like that I sung before.

Irvine and terror in the van;

Came dying all abroad,

And cannon, colours, horse, and man,

Ran tumbling to the road.

Still as he fled, 'twas Irvine's cry,

And his example too,

"Run on, my merry men all--for why?"

The shot will not go through.*

As when two kennels in the street,

Swell'd with a recent rain,

In gashing streams together meet,

And seek the neighbouring drain:

So meet these dung-born tribes in one,

As swift in their career,

And so to New Bridge they ran on--

But all the cows got clear.

* Five refugees ('tis true) were found

Stiff on the block-house floor,

But then 'tis thought the shot went round,

And in at the back door.

Poor Parson Caldwell* all in wonder,

Saw the returning train,

And mourn'd to Wayne the lack of plunder,

For them to steal again.

For 'twas his right to seize the spoil, and

To share with each commander,

As he had done at States Island

With frost-bit Alexander.**

In his dismay, the frantic priest

Began to grow prophetic,

You had swore, to see his lab'ring breast,

He'd taken an emetic.

"I view a future day," said he,

"Brighter than this day dark is,

And you shall see what you shall see,

Ha! ha! one pretty Marquis***

"And he shall come to Pantus Hook****

And great achievements think on,

And make a bow and take a look,

Like Satan over Lincoln.

"And all the land around shall glory

To see the Frenchman caper,

And pretty Susan tell the story

In the next Chatham paper."

This solemn prophecy," of course,

Gave all much consolation,

Except to Wayne, who lost his horse,

Upon the great occasion:

His horse that carried all his prog,

His military speeches,

His corn-stalk whisky for his grog--

Blue stockings and brown breeches.

And now I've closed my epic strain,

I tremble as I show it,

Lest this same warrio-drover, Wayne,

Should ever cate the poet.

* A patriotic preacher of the Gospel, at Elizabethtown,

New Jersey, who was afterwards murdered.

** William Alexander, Lord Stirling.

*** The Marquis de Lafayette.

**** New Jersey city.

It has been remarked as a curious coincidence, that on the day when the last canto of the above poem was published in Rivington's Gazette, Major André was arrested; and that General Wayne, so ridiculed in it, and who is so peculiarly alluded to in the last stanza, was the commander of the military force from which was detailed the guard that accompanied the gifted young officer to the scaffold. On the autograph copy from which I copied the poem, and which André dated "Elizabethtown [New Jersey], August 1, 1780," were the following lines:--

"When this epic strain was sung,

The poet by the neck was hung;

And to his cost he finds too late,

The 'dung-born tribe' decides his fate."

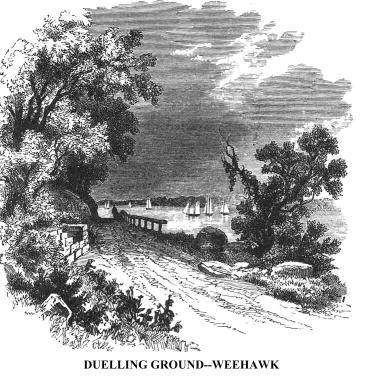

The

next village below Bull's Ferry is Weehawk,* a place of great resort in summer

by pleasure seekers from the metropolis. It is made famous by its connection

with the dueling ground where General Alexander Hamilton, one of the founders

of the Republic, was mortally wounded in single combat, by Aaron Burr, then

Vice-President of the United States. They were bitter political foes. Without

just provocation, in the summer preceding an important election, Burr, anxious

to have Hamilton out of his way, challenged him to fight. The latter, out

of unnecessary respect for a barbarous public opinion, accepted the challenge;

and early in the morning of the 11th of July, 1804, they and friends crossed

the Hudson to Weehawk, and stood as foes upon the dueling ground. Hamilton

was opposed to dueling; and, pursuant to his previous resolution, did not

fire his pistol. The malignant Burr took deliberate aim, and fired with fatal

precision. Hamilton lived little more than thirty hours. His death produced

the most profound grief throughout the nation. Burr lived more than thirty

years, a fugitive, like Cain, and suffering the bitter scorn of his countrymen.

This crime, added to his known vices, made him thoroughly detested, and few

men had the courage to avow themselves his friend. A monument was erected

to the memory of Hamilton, on the spot where he fell. It was afterwards destroyed

by some marauder. The place is now a rough one, on the margin of the river,

and is marked by a rude arm-chair or sofa (seen in our sketch, in which we

are looking up the river) made of stones. On one of them the half-effaced

names of Hamilton and Burr may be seen.

The

next village below Bull's Ferry is Weehawk,* a place of great resort in summer

by pleasure seekers from the metropolis. It is made famous by its connection

with the dueling ground where General Alexander Hamilton, one of the founders

of the Republic, was mortally wounded in single combat, by Aaron Burr, then

Vice-President of the United States. They were bitter political foes. Without

just provocation, in the summer preceding an important election, Burr, anxious

to have Hamilton out of his way, challenged him to fight. The latter, out

of unnecessary respect for a barbarous public opinion, accepted the challenge;

and early in the morning of the 11th of July, 1804, they and friends crossed

the Hudson to Weehawk, and stood as foes upon the dueling ground. Hamilton

was opposed to dueling; and, pursuant to his previous resolution, did not

fire his pistol. The malignant Burr took deliberate aim, and fired with fatal

precision. Hamilton lived little more than thirty hours. His death produced

the most profound grief throughout the nation. Burr lived more than thirty

years, a fugitive, like Cain, and suffering the bitter scorn of his countrymen.

This crime, added to his known vices, made him thoroughly detested, and few

men had the courage to avow themselves his friend. A monument was erected

to the memory of Hamilton, on the spot where he fell. It was afterwards destroyed

by some marauder. The place is now a rough one, on the margin of the river,

and is marked by a rude arm-chair or sofa (seen in our sketch, in which we

are looking up the river) made of stones. On one of them the half-effaced

names of Hamilton and Burr may be seen.

* This is an Indian word, and is thus spelt in its purity. The Dutch spelt it Wiehachan, and it is now commonly written Weehawken; I have adopted the orthography that expresses the pure Indian pronunciation.

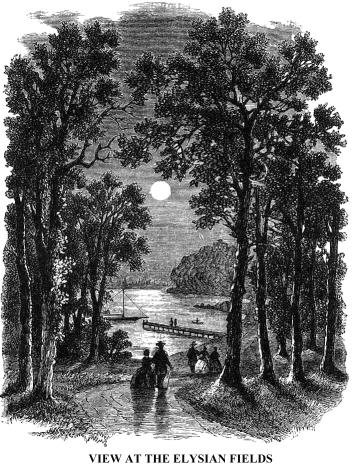

The next place of interest below Weehawk is that known in former times as the Elysian Fields. I remember it as a delightful retreat at "high noon," or by moonlight, for those who loved Nature in her quiet and simple forms. Then there were stately trees near the bank of the river, and from their shades the eye rested upon the busy surface of the stream, or the busier city beyond. There, on a warm summer afternoon, or a moonlit evening, might be seen scores of both sexes strolling upon the soft grass, or sitting upon the green sward, recalling to memory many beautiful sketches of life in the early periods of the world, given in the volumes of the old poets. All is now changed; the trips of Charon to the Elysian Fields are suspended, and the grounds, stripped of many of the noble trees, have become "private," and subjected to the manipulations of the "real estate agent." Even the Sibyl's Cave, under Castle Point, at the southern boundary of the Elysian Fields--a cool, rocky cavern containing a spring--has been spoiled by the clumsy hand of Art.

The

low promontory below Castle Point was the site of the large Indian village

of Hobock. There the pleasant little city of Hoboken now stands, and few of

its quiet denizens are aware of the dreadful tragedy performed in that vicinity

more than two hundred years ago. The story may be related in few words. A

fierce feud had existed for some time between the New Jersey Indians and the

Dutch on Manhattan. Several of the latter had been murdered by the former,

and the Hollanders had resolved on vengeance. At length the fierce Mohawks,

bent on procuring tribute from the weaker tribes westward of the Hudson, came

sweeping down like a gale from the north, driving great numbers of fugitives

upon the Hackensacks at Hobock. Now was the opportunity for the Dutch. A strong

body of them, with some Mohawks, crossed the Hudson at midnight, in February,

1643, fell upon the unsuspecting Indians, and before morning murdered almost

one hundred men, women, and children. Many were driven from the cliffs of

Castle Point, and perished in the freezing flood. At sunrise the murderers

returned to New Amsterdam, with prisoners and the heads of several Indians.

The

low promontory below Castle Point was the site of the large Indian village

of Hobock. There the pleasant little city of Hoboken now stands, and few of

its quiet denizens are aware of the dreadful tragedy performed in that vicinity

more than two hundred years ago. The story may be related in few words. A

fierce feud had existed for some time between the New Jersey Indians and the

Dutch on Manhattan. Several of the latter had been murdered by the former,

and the Hollanders had resolved on vengeance. At length the fierce Mohawks,

bent on procuring tribute from the weaker tribes westward of the Hudson, came

sweeping down like a gale from the north, driving great numbers of fugitives

upon the Hackensacks at Hobock. Now was the opportunity for the Dutch. A strong

body of them, with some Mohawks, crossed the Hudson at midnight, in February,

1643, fell upon the unsuspecting Indians, and before morning murdered almost

one hundred men, women, and children. Many were driven from the cliffs of

Castle Point, and perished in the freezing flood. At sunrise the murderers

returned to New Amsterdam, with prisoners and the heads of several Indians.

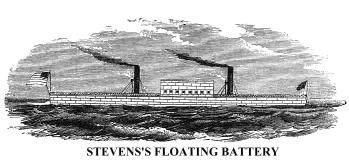

A large proportion of the land at Hoboken is owned by the Stevens

family, who have been identified  with

steam navigation from its earliest triumphs. The head of the family laid out

a village on Hoboken Point, in 1804. It has become a considerable city. Members

of the same family had large manufacturing establishments there; and for several

years before the Civil War had been constructing, upon a novel plan, a huge

floating battery for harbour defences, for the government of the United States,

and more than a million of dollars had already been spent in its construction,

when the war broke out. It had been utterly shut in from the public eye, until

a very short time before that event. Our space will allow nothing more than

an outline description of it. It is a vessel seven hundred feet long (length

of the Great Eastern), covered with plates of iron so as to be absolutely

bomb and round shot proof. It is to be moved by steam engines of sufficient

power to give it a momentum that will cause it to cut a man-of-war in two,

when it strikes it at the waists. It will mount a battery of sixteen heavy

rifled cannon in bomb-proof casemates, and two heavy columbiads for throwing

shells will be on deck, one forward and one aft. The smoke-pipe is constructed

in sliding sections, like a telescope, for obvious purposes; and the huge

vessel may be sunk so that its decks alone will be above the water. It is

to be rated at six thousand tons. The war was productive of a variety of iron-clad

vessels far more effective than this promises to be, and it is probable that

it will never be completed.

with

steam navigation from its earliest triumphs. The head of the family laid out

a village on Hoboken Point, in 1804. It has become a considerable city. Members

of the same family had large manufacturing establishments there; and for several

years before the Civil War had been constructing, upon a novel plan, a huge

floating battery for harbour defences, for the government of the United States,

and more than a million of dollars had already been spent in its construction,

when the war broke out. It had been utterly shut in from the public eye, until

a very short time before that event. Our space will allow nothing more than

an outline description of it. It is a vessel seven hundred feet long (length

of the Great Eastern), covered with plates of iron so as to be absolutely

bomb and round shot proof. It is to be moved by steam engines of sufficient

power to give it a momentum that will cause it to cut a man-of-war in two,

when it strikes it at the waists. It will mount a battery of sixteen heavy

rifled cannon in bomb-proof casemates, and two heavy columbiads for throwing

shells will be on deck, one forward and one aft. The smoke-pipe is constructed

in sliding sections, like a telescope, for obvious purposes; and the huge

vessel may be sunk so that its decks alone will be above the water. It is

to be rated at six thousand tons. The war was productive of a variety of iron-clad

vessels far more effective than this promises to be, and it is probable that

it will never be completed.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.