Chapter Two, Part Two

That

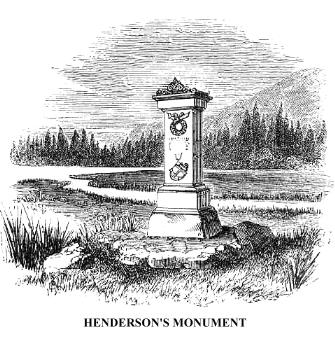

tiny lake is called Calamity Pond, in commemoration of a sad circumstance

that occurred near the spot where we erected our cabin, in September, 1845.

Mr. Henderson, of the Adirondack Iron Company, already mentioned, was there

with his son and other attendants. Near the margin of the inlet is a flat

rock. On this, as he landed from a scow, Mr. Henderson attempted to lay his

pistol, holding the muzzle in his hand. It discharged, and the contents entering

his body, wounded him mortally: he lived only half-an-hour. A rude bier was

constructed of boughs, on which his body was carried to Adirondack village.

It was taken down Sandford Lake in a boat to Tahawus, and from thence again

carried on a bier through the wilderness, fifteen miles to the western termination

of the road from Scarron valley, then in process of construction. From thence

it was conveyed to his home at Jersey City, and a few years afterward his

family erected an elegant monument upon the rock where he lost his life. It

is of the light New Jersey sandstone, eight feet in height, and bears the

following inscription:--"This monument was erected by filial affection

to the memory of David Henderson, who lost his life on this spot, 3rd September,

1845." Beneath the inscription, in high relief, is a chalice, book, and

anchor.

That

tiny lake is called Calamity Pond, in commemoration of a sad circumstance

that occurred near the spot where we erected our cabin, in September, 1845.

Mr. Henderson, of the Adirondack Iron Company, already mentioned, was there

with his son and other attendants. Near the margin of the inlet is a flat

rock. On this, as he landed from a scow, Mr. Henderson attempted to lay his

pistol, holding the muzzle in his hand. It discharged, and the contents entering

his body, wounded him mortally: he lived only half-an-hour. A rude bier was

constructed of boughs, on which his body was carried to Adirondack village.

It was taken down Sandford Lake in a boat to Tahawus, and from thence again

carried on a bier through the wilderness, fifteen miles to the western termination

of the road from Scarron valley, then in process of construction. From thence

it was conveyed to his home at Jersey City, and a few years afterward his

family erected an elegant monument upon the rock where he lost his life. It

is of the light New Jersey sandstone, eight feet in height, and bears the

following inscription:--"This monument was erected by filial affection

to the memory of David Henderson, who lost his life on this spot, 3rd September,

1845." Beneath the inscription, in high relief, is a chalice, book, and

anchor.

The lane through the woods just mentioned was cut for the purpose of allowing the transportation of this monument upon a sledge in winter, drawn by oxen. All the way the road was made passable by packing the snow between the boulders, and in this labour several days were consumed. The monument weighs a ton.

While Preston and myself were building the bark cabin, in a manner similar to the bush one already described, and Mrs. Lossing was preparing a place upon the clean grass near the fire for our supper, Mr. Buckingham and Sabattis went out upon the lake on a rough raft, and caught over two dozen trout. Upon these we supped and breakfasted. The night was cold, and at early dawn we found the hoar-frost lying upon every leaf and blade around us. Beautiful, indeed, was that dawning of the last day of summer. From the south-west came a gentle breeze, bearing upon its wings light vapour, that flecked the whole sky, and became roseate in hue when the sun touched with purple light the summit of the hills westward of us. These towered in grandeur more than a thousand feet above the surface of the lake, from which, in the kindling morning light, went up, in myriads of spiral threads, a mist, softly as a spirit, and melted in the first sunbeam.

At eight o'clock we resumed our journey over a much rougher way than we had yet traveled, for there was nothing but a dim and obstructed hunter's trail to follow. This we pursued nearly two miles, when we struck the outlet of Lake Colden, at its confluence with the Opalescent River, that comes rushing down in continuous rapids and cascades from the foot of Tahawus. The lake was only a few rods distant. Intending to visit it on our return, we contented ourselves with brief glimpses of it through the trees, and of tall Mount Colden, or Mount M'Martin, that rises in magnificence from its eastern shore.

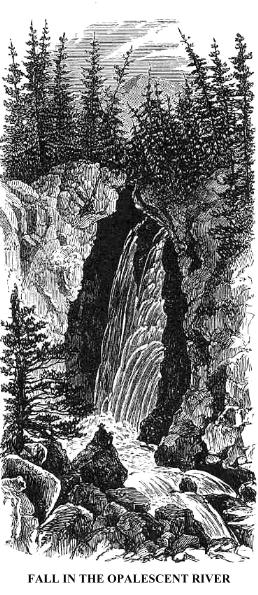

The drought that still prevailed over northern New York and New England had so diminished the volume of the Opalescent River, that we walked more than four miles in the bed of the stream upon boulders which fill it. We crossed it a hundred times or more, picking our way, and sometimes compelled to go into the woods in passing a cascade. The stream is broken into falls and swift rapids the whole distance that we followed it, and, when full, it must present a grand spectacle. At one place the river had assumed the bed of a displaced trap dyke, by which the rock has been intersected. The walls are perpendicular, and only a few feet apart--so near that the branches of the trees on the summits interlace. Through this the water rushes for several rods, and then leaps into a dark chasm, full fifty feet perpendicular, and emerges among a mass of immense boulders. The Indians called this cascade She-gwi-en-dawkwe, or the Hanging Spear. A short distance above is a wild rapid, which they called Kas-kong-shadi, or Broken Water.

The stones in this river vary in size, from tiny pebbles to boulders of a thousand tons; the smaller ones made smooth by rolling, the larger ones, yet angular and massive, persistently defying the rushing torrent in its maddest career. They are composed chiefly of the beautiful labradorite, or opalescent feldspar, which form the great mass of the Aganus-chion, or Black Mountain range, as the Indians called this Adirondack group, because of the dark aspect which their sombre cedars, and spruce, and cliffs present at a distance. The bed of the stream is full of that exquisitely beautiful mineral. We saw it glittering in splendour, in pebbles and large boulders, when the sunlight fell full upon the shallow water. A rich blue is the predominant colour, sometimes mingled with a brilliant green. Gold and bronze-coloured specimens have been discovered, and, occasionally, a completely iridescent piece may be found. It is to the abundance of these stones that the river is indebted for its beautiful name. It is one of the main sources of the Hudson, and falls into Sandford Lake, a few miles below Adirondack village.

We

followed the Opalescent River to the foot of the Peak of Tahawus, on the borders

of the high valley which separates that mountain from Mount Colden, at an

elevation nine hundred feet above the highest peaks of the Cattskill range

on the Lower Hudson. There the water is very cold, the forest trees are somewhat

stunted and thickly planted, and the solitude complete. The silence was almost

oppressive. Game-birds and beasts of the chase are there almost unknown. The

wild cat and wolverine alone prowl over that lofty valley, where rises one

of the chief fountains of the Hudson, and we heard the voice of no living

creature excepting the hoarse croak of the raven.

We

followed the Opalescent River to the foot of the Peak of Tahawus, on the borders

of the high valley which separates that mountain from Mount Colden, at an

elevation nine hundred feet above the highest peaks of the Cattskill range

on the Lower Hudson. There the water is very cold, the forest trees are somewhat

stunted and thickly planted, and the solitude complete. The silence was almost

oppressive. Game-birds and beasts of the chase are there almost unknown. The

wild cat and wolverine alone prowl over that lofty valley, where rises one

of the chief fountains of the Hudson, and we heard the voice of no living

creature excepting the hoarse croak of the raven.

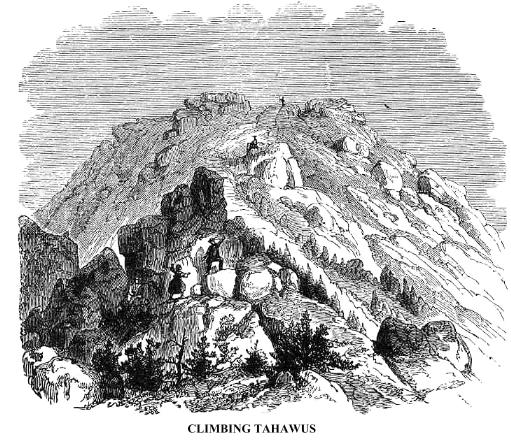

It was noon when we reached this point of departure for the

summit of Tahawus. We had been four hours traveling six miles, and yet in

that pure mountain air we felt very little fatigue. There we found an excellent

bark "camp," and traces of recent occupation. Among them was part

of a metropolitan newspaper, and light ashes. We dined upon bread and butter

and maple sugar, in a sunny spot in front of the cabin, and then commenced

the ascent, leaving our provisions and other things at the camp, where we

intended to repose for the night. The journey upward was two miles, at an

angle of forty-five degrees to the base of the rocky pinnacle. We had no path

to follow. The guides "blazed" the larger trees (striking off chips

with their axes), that they might with more ease find their way back to the

camp. Almost the entire surface was covered with boulders, shrouded in the

most beautiful alpine mosses. From among these shot up dwarfing pines and

spruces, which diminished in height at every step. Through their thick horizontal

branches it was difficult to pass. Here and there among the rocks was a free

spot, where the bright trifoliolate oxalis, or wood-sorrel, flourished, and

the shrub of the wild currant, and gooseberry, and the tree-cranberry appeared.

At length we reached the foot of the open rocky pinnacle, where only thick mosses, lichens, a few alpine plants, and little

groves of dwarfed balsam, are seen. The latter trees, not more than five feet

in height, are, most of them, centenarians. Their stems, not larger than a

strong man's wrist, exhibited, when cut, over one hundred concentric rings,

each of which indicates the growth of a year. Our journey now became still

more difficult, at the same time more interesting, for, as we emerged from

the forest, the magnificent panorama of mountains that lay around us burst

upon the vision. Along steep rocky slopes and ledges, and around and beneath

huge stones a thousand tons in weight, some of them apparently poised, as

if ready for a sweep down the mountain, we made our way cautiously, having

at times no other support than the strong moss, and occasionally a gnarled

shrub that sprung from the infrequent fissures. We rested upon small terraces,

where the dwarf balsams grow. Upon one of these, within a hundred feet of

the summit, we found a spring of very cold water, and near it quite thick

ice. This spring is one of the remote sources of the Hudson. It bubbles from

the base of a huge mass of loose rocks (which, like all the other portions

of the peak, are composed of the beautiful labradorite), and sends down a

little stream into the Opalescent River, from whose bed we

pinnacle, where only thick mosses, lichens, a few alpine plants, and little

groves of dwarfed balsam, are seen. The latter trees, not more than five feet

in height, are, most of them, centenarians. Their stems, not larger than a

strong man's wrist, exhibited, when cut, over one hundred concentric rings,

each of which indicates the growth of a year. Our journey now became still

more difficult, at the same time more interesting, for, as we emerged from

the forest, the magnificent panorama of mountains that lay around us burst

upon the vision. Along steep rocky slopes and ledges, and around and beneath

huge stones a thousand tons in weight, some of them apparently poised, as

if ready for a sweep down the mountain, we made our way cautiously, having

at times no other support than the strong moss, and occasionally a gnarled

shrub that sprung from the infrequent fissures. We rested upon small terraces,

where the dwarf balsams grow. Upon one of these, within a hundred feet of

the summit, we found a spring of very cold water, and near it quite thick

ice. This spring is one of the remote sources of the Hudson. It bubbles from

the base of a huge mass of loose rocks (which, like all the other portions

of the peak, are composed of the beautiful labradorite), and sends down a

little stream into the Opalescent River, from whose bed we  had

just ascended. Mr. Buckingham had now gained the summit, and waved his hat,

in token of triumph, and a few minutes later we were at his side, forgetful,

in the exhilaration of the moment, of every fatigue and danger that we had

encountered. Indeed it was a triumph for us all, for few persons have ever

attempted the ascent of that mountain, lying in a deep wilderness, hard to

penetrate, the nearest point of even a bridle path, on the side of our approach,

being ten miles from the base of its peak. Especially difficult is it for

the feet of woman to reach the lofty summit of the Sky-piercer--almost six

thousand feet above the sea--for her skirts form great impediments. Mrs. Lossing,

we were afterwards informed by the oldest hunter and guide in all that region

(John Cheney), is only the third woman who has ever accomplished the difficult

feat.

had

just ascended. Mr. Buckingham had now gained the summit, and waved his hat,

in token of triumph, and a few minutes later we were at his side, forgetful,

in the exhilaration of the moment, of every fatigue and danger that we had

encountered. Indeed it was a triumph for us all, for few persons have ever

attempted the ascent of that mountain, lying in a deep wilderness, hard to

penetrate, the nearest point of even a bridle path, on the side of our approach,

being ten miles from the base of its peak. Especially difficult is it for

the feet of woman to reach the lofty summit of the Sky-piercer--almost six

thousand feet above the sea--for her skirts form great impediments. Mrs. Lossing,

we were afterwards informed by the oldest hunter and guide in all that region

(John Cheney), is only the third woman who has ever accomplished the difficult

feat.

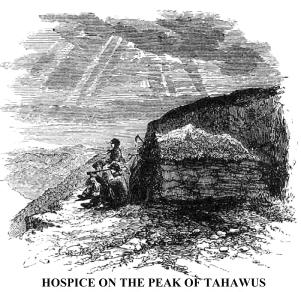

The summit of Tahawus is bare rock, about four hundred feet in length and one hundred in breadth, with an elevation of ten or twelve feet at the south-western end, that may be compared to the heel of an upturned boot, the remainder of the surface forming the sole. In a nook on the southern side of this heel, was a small hut, made of loose stones gathered from the summit, and covered with moss. It was erected the previous year by persons from New York, and had been occupied by others a fortnight before our visit. Within the hut we found a piece of paper, on which was written:--"This hospice, erected by a party from New York, August 19, 1858, is intended for the use and comfort of visitors to Tahawns.--F. S. P.--M. C.--F. M. N." Under this was written:--"This hospice was occupied over night of August 14, 1859, by A.G.C. and T.R.D. Sun rose fourteen minutes to five." Under this:--" Tahawus House Register, August 14, 1859, Alfred G. Compton, and Theodore R. Davis, New York. August 16, Charles Newman, Stamford, Connecticut; Charles Bedfield, Elizabeth Town, New York." To these we added our own names, and those of the guides.

Our view from the summit of Tahawus will ever form one of the

most remarkable pictures in memory; and yet it may not properly be called a picture. It is a topographical map, exhibiting

a surface diversified by mountains, lakes, and valleys. The day was very pleasant,

yet a cold north-westerly wind was sweeping over the summit of the mountain.

A few clouds, sufficient to cast fine shadows upon the earth, were floating

not far above us, and on the east, when we approached the summit at three

o'clock, an iridescent mist was slightly veiling a group of mountains, from

their thick wooded bases in the valleys, to their bold rocky summits. Our

stand-point being the highest in all that region, there was nothing to obstruct

the view. To-war-loon-dah, or Hill of Storms (Mount Emmons),

Ou-kor-lah, or Big Eye (Mount Seward), Wah-o-par-te-nie, or

White-face Mountain, and the Giant of the Valley--all rose peerless above

the other hills around us, excepting Colden and M'Intyre, that stood apparently

within trumpet-call of Tahawus, as fitting companions, but over whose summits,

likewise, we could look away to the dark forests of Franklin and St. Lawrence

Counties, in the far north-west. Northward we could see the hills melting

into the great St. Lawrence level, out of which arose the Royal Mountain back

of the city of Montreal. Eastward, full sixty miles distant, lay the magnificent

Green Mountains, that give name to the state of Vermont, and through a depression

of that range, we saw distinctly the great Mount Washington among the White

Hills of New Hampshire, one hundred and fifty miles distant. Southward the

view was bounded by the higher peaks of the Cattskills, or Katzbergs, and

westward by the mountain ranges in Hamilton and Herkimer Counties. At our

feet reposed the great wilderness of northern New York, full a hundred miles

in length, and eighty in breadth, lying in parts of seven counties, and equal

in area to several separate smaller States of the Union. On every side bright

lakes were gleaming, some nestling in unbroken forests, and others with their

shores sparsely dotted with clearings, from which arose the smoke from the

settler's cabin. We counted twenty-seven lakes, including Champlain--the Indian

Can-i-a-de-ri Gua-run-te, or Door of the Country--which stretched along

the eastern view one hundred and forty miles, and at a distance of about fifty

miles at the nearest point. We could see the sails of water-craft like white

specks upon its bosom, and, with our telescope, could distinctly discern the

houses in Burlington, on the eastern shore of the lake.

yet it may not properly be called a picture. It is a topographical map, exhibiting

a surface diversified by mountains, lakes, and valleys. The day was very pleasant,

yet a cold north-westerly wind was sweeping over the summit of the mountain.

A few clouds, sufficient to cast fine shadows upon the earth, were floating

not far above us, and on the east, when we approached the summit at three

o'clock, an iridescent mist was slightly veiling a group of mountains, from

their thick wooded bases in the valleys, to their bold rocky summits. Our

stand-point being the highest in all that region, there was nothing to obstruct

the view. To-war-loon-dah, or Hill of Storms (Mount Emmons),

Ou-kor-lah, or Big Eye (Mount Seward), Wah-o-par-te-nie, or

White-face Mountain, and the Giant of the Valley--all rose peerless above

the other hills around us, excepting Colden and M'Intyre, that stood apparently

within trumpet-call of Tahawus, as fitting companions, but over whose summits,

likewise, we could look away to the dark forests of Franklin and St. Lawrence

Counties, in the far north-west. Northward we could see the hills melting

into the great St. Lawrence level, out of which arose the Royal Mountain back

of the city of Montreal. Eastward, full sixty miles distant, lay the magnificent

Green Mountains, that give name to the state of Vermont, and through a depression

of that range, we saw distinctly the great Mount Washington among the White

Hills of New Hampshire, one hundred and fifty miles distant. Southward the

view was bounded by the higher peaks of the Cattskills, or Katzbergs, and

westward by the mountain ranges in Hamilton and Herkimer Counties. At our

feet reposed the great wilderness of northern New York, full a hundred miles

in length, and eighty in breadth, lying in parts of seven counties, and equal

in area to several separate smaller States of the Union. On every side bright

lakes were gleaming, some nestling in unbroken forests, and others with their

shores sparsely dotted with clearings, from which arose the smoke from the

settler's cabin. We counted twenty-seven lakes, including Champlain--the Indian

Can-i-a-de-ri Gua-run-te, or Door of the Country--which stretched along

the eastern view one hundred and forty miles, and at a distance of about fifty

miles at the nearest point. We could see the sails of water-craft like white

specks upon its bosom, and, with our telescope, could distinctly discern the

houses in Burlington, on the eastern shore of the lake.

From our point of view we could comprehend the emphatic significance of the Indian idea of Lake Champlain-- the Door of the Country. It fills the bottom of an immense valley, that stretches southward between the great mountain ranges of New York and New England, from the St. Lawrence level toward the valley of the Hudson, from which it is separated by a slightly elevated ridge.* To the fierce Huron of Canada, who loved to make war upon the more southern Iroquois, this lake was a wide open door for his passage. Through it many brave men, aborigines and Europeans, have gone to the war-paths of New York and New England, never to return.

Standing upon Tahawus, it required very little exercise of the imagination to behold the stately procession of historic men and events, passing through that open door. First in dim shadows were the dusky warriors

* In the introduction to his published sermon, preached at Plymouth, in New England, in the year 1621 (and the first ever preached there), the Rev. Robert Cushman, speaking of that country, says:-- "So far as we can find, it is an island, and near about the quantity of England, being cut out from the mainland in America, as England is from the main of Europe, by a great arm of the sea. [Hudson's River], which entereth in forty degrees, and runneth up north-west and by west, and goeth out, either into the South Sea [Pacific Ocean], or else into the Bay of Canada [the Gulf of St. Lawrence]". The old divine was nearly right in his conjecture that New England was an island. It is a peninsula, connected to the main by a very narrow isthmus, the extremities of which are at the villages of Whitehall, on Lake Champlain, and Fort Edward, on the Hudson, about twenty-five miles apart. The lowest portion of that isthmus is not more than fifty feet above Lake Champlain, whose waters are only ninety above the sea. This isthmus is made still narrower by the waters of Wood Creek, which flow into Lake Champlain, and of Fort Edward Creek, which empty into the Hudson. These are navigable for light canoes, at some seasons of the year, to within a mile and a half of each others. The canal, which now connects the Hudson and Lake Champlain, really makes New England and island.

of the ante-Columbian period, darting swiftly through in their bark canoes, intent upon blood and plunder. Then came Champlain and his men [1609], with guns and sabres, to aid the Hurons in contests with the Adirondacks and other Iroquois at Crown Point and Ticonderoga. Then came French and Indian allies, led by Marin [1745], passing swiftly through that door, and sweeping with terrible force down the Hudson valley to Saratoga, to smite the Dutch and English settlers there. Again French and Indian warriors came, led by Montcalm, Dieskau, and others [1755-1759], to drive the English from that door, and secure it for the house of Bourbon. A little later came troops of several nationalities, with Burgoyne at their head [1777], rushing through that door with power, driving American republicans southward, like chaff before the wind, and sweeping victoriously down the valley of the Hudson to Saratoga and beyond. And, lastly, came another British force, with Sir George Prevost at their head [1814], to take possession of that door, but were turned back at the northern threshold with discomfiture. In the peaceful present that door stands wide open, and people of all nations may pass through it unquestioned. But the Indian is seldom seen at the portal.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.