Chapter Three, Part Two

This was the "darkness just before daylight," for

we soon struck a branch of the Scarron, rushing in cascades through a rocky

ravine, along whose banks we found an excellent road. The surrounding country

was very rugged in appearance. The rocky hills had been denuded by fire, and

everything in nature presented a strong contrast to the scene that burst upon

the vision at sunset, when, from the brow of a hill, we saw the beautiful

Scarron valley smiling before us. In a few minutes we crossed the Scarron

River over a covered bridge, and found ourselves fairly out of the wilderness,

at a new and spacious inn, kept by Russell Root, a small, active, and obliging

man, well known all over that northern country. His house was the point of

departure and arrival for those who take what may be called the lower route

to and from the hunting and fishing grounds of the Upper Hudson, and the group

of lakes beyond. Over his door a pair of enormous moose  horns

formed an appropriate signboard, for he was both quarter-master and commissary

of sportsmen in that region. At his house everything necessary for the woods

and waters might be obtained.

horns

formed an appropriate signboard, for he was both quarter-master and commissary

of sportsmen in that region. At his house everything necessary for the woods

and waters might be obtained.

The Scarron, or Schroon River, is the eastern branch of the Hudson. It rises in the heart of Essex County, and flowing southward into Warren county, receiving in its course the waters of Paradox and Scarron, or Schroon Lake, and a large group of ponds, forms a confluence, near Warrensburg, with the main waters of the Hudson, that come down from the Adirondack region. The name of Schroon for this branch is fixed in the popular mind, appears in books and on maps, and is heard upon every lip. It is a corruption of Scarron, the name given to the lake by French officers, who were stationed at Fort St. Frederick, on Crown Point, at the middle of the last century. In their rambles in the wilderness on the western shore of Lake Champlain, they discovered a beautiful lake, and named it in gallant homage to the memory of the widow of the poet Scarron, who, as Madame de Maintenon, became the queen of Louis XIV, of France. The name was afterwards applied to the river, and the modern corrupt orthography and pronunciation were unknown before the present century, at the beginning of which settlements were first commenced in that region. In the face of legal documents, common speech, and maps, we may rightfully call it Scarron; for the antiquity and respectability of an error are not valid excuses for perpetuating it.

From Root's we rode down the valley to the pleasant little

village on the western shore of Scarron  Lake.

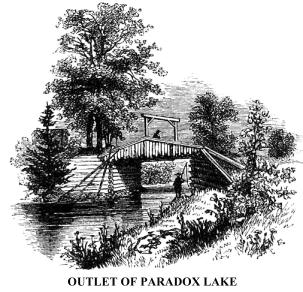

We turned aside to visit the beautiful Paradox Lake, nestled among wooded

hills a short distance from the river. It is separated from Scarron Lake by

a low alluvial drift, and is so nearly on a level with the river into which

it empties, that when torrents from the hills swell the waters of that stream,

a current flows back into Paradox Lake, making its outlet an inlet for the

time. From this circumstance it received its name. We rode far up its high

southern shore to enjoy many fine views of the lake and its surroundings,

and returning, lunched in the shadows of trees at a rustic bridge that spans

its outlet a few rods below the lake.

Lake.

We turned aside to visit the beautiful Paradox Lake, nestled among wooded

hills a short distance from the river. It is separated from Scarron Lake by

a low alluvial drift, and is so nearly on a level with the river into which

it empties, that when torrents from the hills swell the waters of that stream,

a current flows back into Paradox Lake, making its outlet an inlet for the

time. From this circumstance it received its name. We rode far up its high

southern shore to enjoy many fine views of the lake and its surroundings,

and returning, lunched in the shadows of trees at a rustic bridge that spans

its outlet a few rods below the lake.

Scarron Lake is a beautiful sheet of water, ten miles in length, and about a mile in average width. It is ninety miles north of Albany, and lies partly in Essex and partly in Warren County. Its aspect is interesting from every point of view. The gentle slopes on its western shore are well cultivated and thickly inhabited, the result of sixty years' settlement, but on its eastern shore are precipitous and rugged hills, which extend in wild and picturesque succession to Lake Champlain, fifteen or twenty miles distant. In the bosom of these hills, and several hundred feet above the Scarron, lies Lake Pharaoh, a body of cold water surrounded by dark mountains, and near it is a large cluster of ponds, all of which find a receiving reservoir in Scarron Lake, and make its outlet a large stream.

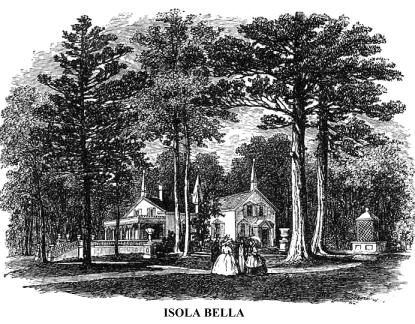

In the lake directly in front of Scarron village is an elliptical

island, containing about one hundred  acres.

It was purchased a few years ago by Colonel A.L. Ireland, a wealthy gentleman

of New York, who went there in search of health, and who spent large sums

of money in subduing the savage features of the island, erecting a pleasant

summer mansion upon it, and in changing the rough and forbidding aspect of

the whole domain into one of beauty and attractiveness. Taste and labour had

wrought wonderful changes there, and its appearance justified the title it

bore of Isola Bella--the Indian Cay-wa-noot. The mansion was cruciform,

and delightfully situated. In front of it were tastefully ornamented grounds,

with vistas through the forest trees, that afforded glimpses of charming lake,

landscape, and distant mountain scenery. Within were evidences of elegant

refinement--a valuable library, statuary, bronzes, and some rare paintings.

Among other sketches was a picture of Hale Hall, in Lancashire, England--the

ancestral dwelling of Colonel Ireland, who is a lineal descendant of Sir John

de Ireland, a Norman baron who accompanied William the Conqueror to England,

was at the battle of Hastings, and received from the monarch a large domain,

upon which he built a castle. On the site of that castle, Hale Hall was erected

by Sir Gilbert Ireland, who was a member of parliament, and lord-lieutenant

of his county. Hale Hall remains in possession of the family.

acres.

It was purchased a few years ago by Colonel A.L. Ireland, a wealthy gentleman

of New York, who went there in search of health, and who spent large sums

of money in subduing the savage features of the island, erecting a pleasant

summer mansion upon it, and in changing the rough and forbidding aspect of

the whole domain into one of beauty and attractiveness. Taste and labour had

wrought wonderful changes there, and its appearance justified the title it

bore of Isola Bella--the Indian Cay-wa-noot. The mansion was cruciform,

and delightfully situated. In front of it were tastefully ornamented grounds,

with vistas through the forest trees, that afforded glimpses of charming lake,

landscape, and distant mountain scenery. Within were evidences of elegant

refinement--a valuable library, statuary, bronzes, and some rare paintings.

Among other sketches was a picture of Hale Hall, in Lancashire, England--the

ancestral dwelling of Colonel Ireland, who is a lineal descendant of Sir John

de Ireland, a Norman baron who accompanied William the Conqueror to England,

was at the battle of Hastings, and received from the monarch a large domain,

upon which he built a castle. On the site of that castle, Hale Hall was erected

by Sir Gilbert Ireland, who was a member of parliament, and lord-lieutenant

of his county. Hale Hall remains in possession of the family.

We were conveyed to Isola Bella in a skiff, rowed by two watermen, in the face of a stiff breeze that ruffled the lake, and it was almost sunset when we returned to the village of Scarron Lake. It was Saturday evening, and we remained at the village until Monday morning, and then rode down the pleasant valley to Warrensburg, near the junction of the Scarron and the west branch of the Hudson, a distance of almost thirty miles. It was a very delightful ride, notwithstanding we were menaced by a storm. Our road lay first along the cultivated western margin of the lake, and thence through a rolling valley, from which we caught occasional glimpses of the river, sometimes near and sometimes distant. The journey occupied a greater portion of the day. We passed two quiet villages, named respectively Pottersville and Chester. The latter, the larger of the two, is at the outlet of Loon and Friendship Lakes--good fishing places, a few miles distant. Both villages are points upon the State road, from which sportsmen depart for the adjacent woods and waters. An hour's ride from either place will put them within the borders of the great wilderness, and beyond the sounds of the settlements.

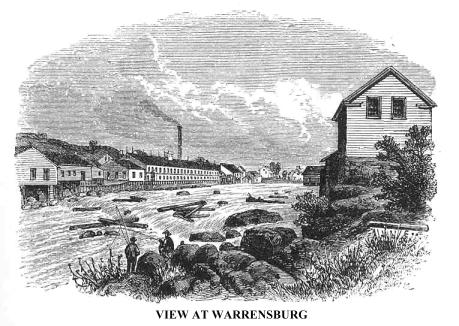

Warrensburg is situated partly upon a high plain and partly

upon a slope that stoops to a bend of the Scarron, about two miles above its

confluence with the west branch of the Hudson. It was a village of about seven

hundred inhabitants, in the midst of rugged mountain scenery, the hills abounding

with iron ore. As we approached it we came to a wide plain, over which lay--in

greater perfection than any we had yet seen--stump fences, which are peculiar

to the Upper Hudson country. They are composed of the stumps of large pine-trees,

drawn from the soil by machines made for the purpose, and they are so disposed

in rows, their roots interlocking, as to form an effectual barrier to the

passage of any animal on whose account fences are made. The stumps are full

of sap (turpentine), and we were assured, with all the confidence of experience,

that these fences would last a thousand years, the turpentine preserving the

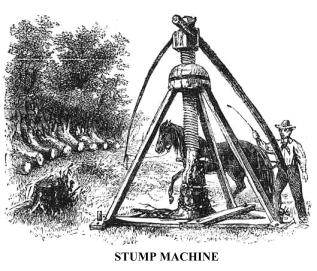

woody fibre. One of the stump-machines stood in a field near the road. It was a simple derrick,

with a large wooden screw hanging from the apex, where its heavy matrix was

fastened. In the lower end of the screw was a large iron bolt, and at the

upper end, or head, a strong lever was fastened. The derrick is placed over

a stump, and heavy chains are wound round and under the stump and over the

iron bolt in the screw. A horse attached to the lever works the screw in such

a manner as to draw the stump and its roots clean from the ground. The stump

fences formed quite a picturesque feature in the landscape, and at a distance

have the appearance of masses of deer horns.

the stump-machines stood in a field near the road. It was a simple derrick,

with a large wooden screw hanging from the apex, where its heavy matrix was

fastened. In the lower end of the screw was a large iron bolt, and at the

upper end, or head, a strong lever was fastened. The derrick is placed over

a stump, and heavy chains are wound round and under the stump and over the

iron bolt in the screw. A horse attached to the lever works the screw in such

a manner as to draw the stump and its roots clean from the ground. The stump

fences formed quite a picturesque feature in the landscape, and at a distance

have the appearance of masses of deer horns.

It

was toward evening when we arrived at Warrensburg, but before sunset we had

strolled over the most interesting portions of the village, along the river

and its immediate vicinity. Here, as elsewhere, the prevailing drought had

diminished the streams, and the Scarron, usually a wild, rushing river, from

the village to its confluence with the Hudson proper, was a comparatively

gentle creek, with many of the rocks in its bed quite bare, and timber lodged

among them. The buildings of a large manufactory of leather skirted one side

of the rapids, and at their head was a large dam and some mills. That region

abounded with establishments for making leather, the hemlock-tree, whose bark

is used for tanning, being very abundant upon the mountains.

It

was toward evening when we arrived at Warrensburg, but before sunset we had

strolled over the most interesting portions of the village, along the river

and its immediate vicinity. Here, as elsewhere, the prevailing drought had

diminished the streams, and the Scarron, usually a wild, rushing river, from

the village to its confluence with the Hudson proper, was a comparatively

gentle creek, with many of the rocks in its bed quite bare, and timber lodged

among them. The buildings of a large manufactory of leather skirted one side

of the rapids, and at their head was a large dam and some mills. That region

abounded with establishments for making leather, the hemlock-tree, whose bark

is used for tanning, being very abundant upon the mountains.

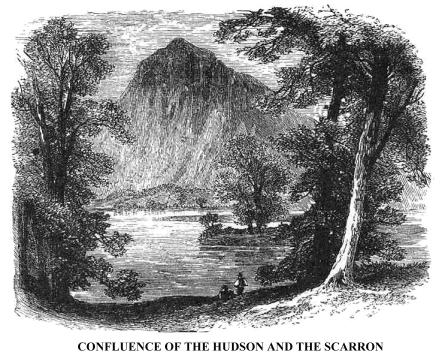

We passed the night at Warrensburg, and early in the morning rode to the confluence of the Scarron and Hudson rivers, in a charming little valley which formed the Indian pass of Teo-ho-Ken in the olden time, between the Thunder's Nest and other high hills. The point where the waters met was a lovely spot, shaded by elms and other spreading trees, and forming a picture of beauty and repose in strong contrast with the rugged hills around. On the north side of the valley rises the Thunder's Nest (which appears in our little sketch), a lofty pile of rocks full eight hundred feet in height; and from the great bridge, three hundred feet long, which spanned the Hudson just below the confluence, there was a view of a fine amphitheatre of hills.

From Tahawus, at the foot of Sandford Lake, to the confluence

with the Scarron, at Warrensburg,  a

distance of about fifty miles by its course, the Hudson flows most of the

way through an almost unbroken wilderness. Through that region an immense

amount of timber is annually east into the stream, to be gathered by the owners

at the great boom near Glen's Falls. From Warrensburg to Luzerne, at Jesup's

Little Falls, the river is equally uninteresting, and these two sections we

omitted in our explorations, because they promised very small returns for

the time and labour to be spent in visiting them. So at Warrensburg we left

the river again, and took a somewhat circuitous route to Luzerne, that we

might travel a good road. That route, by far the most interesting for the

tourist, leads by the way of Caldwell, at the head of Lake George, through

a mountainous and very picturesque country, sparsely dotted with neat farmhouses

in the intervals between the grand old hills. The road is planked, and occasionally

a fountain by the wayside sends out its clear stream from rocks, or a mossy

bank, into a rude reservoir, such as is seen delineated in the picture at

the head of Chapter II. While watering our horses at one of these, the ring

of merry laughter came up through the little valley near, and a few moments

afterward we met a group of young people enjoying the pleasures of a pic-nic.

a

distance of about fifty miles by its course, the Hudson flows most of the

way through an almost unbroken wilderness. Through that region an immense

amount of timber is annually east into the stream, to be gathered by the owners

at the great boom near Glen's Falls. From Warrensburg to Luzerne, at Jesup's

Little Falls, the river is equally uninteresting, and these two sections we

omitted in our explorations, because they promised very small returns for

the time and labour to be spent in visiting them. So at Warrensburg we left

the river again, and took a somewhat circuitous route to Luzerne, that we

might travel a good road. That route, by far the most interesting for the

tourist, leads by the way of Caldwell, at the head of Lake George, through

a mountainous and very picturesque country, sparsely dotted with neat farmhouses

in the intervals between the grand old hills. The road is planked, and occasionally

a fountain by the wayside sends out its clear stream from rocks, or a mossy

bank, into a rude reservoir, such as is seen delineated in the picture at

the head of Chapter II. While watering our horses at one of these, the ring

of merry laughter came up through the little valley near, and a few moments

afterward we met a group of young people enjoying the pleasures of a pic-nic.

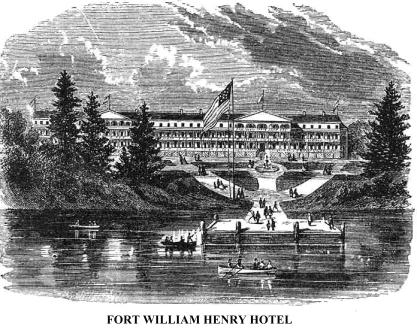

At

noon we reined up in front of the Fort William Henry Hotel, at the head of

Lake George, where we dined, and then departed through the forest for Luzerne.

That immense caravansera for the entertainment of summer visitors stands upon

classic ground. It is upon the site of old Fort William Henry, erected by

General William Johnson in the autumn of 1755, and named in honour of two

of the Royal Family of England. At the same time the general changed the name

of the lake from that of the Holy Sacrament, given it by Father Jogue, a French

priest, who reached the head of it on Corpus Christi day, to George--not

in simple honour to his Majesty, then reigning monarch of England, but, as

the general said, "to assert his undoubted dominion here." The Indians

called it, Can-at-de-ri-oit, or Tale of the Lake, it appearing as

such appendage to Lake Champlain.

At

noon we reined up in front of the Fort William Henry Hotel, at the head of

Lake George, where we dined, and then departed through the forest for Luzerne.

That immense caravansera for the entertainment of summer visitors stands upon

classic ground. It is upon the site of old Fort William Henry, erected by

General William Johnson in the autumn of 1755, and named in honour of two

of the Royal Family of England. At the same time the general changed the name

of the lake from that of the Holy Sacrament, given it by Father Jogue, a French

priest, who reached the head of it on Corpus Christi day, to George--not

in simple honour to his Majesty, then reigning monarch of England, but, as

the general said, "to assert his undoubted dominion here." The Indians

called it, Can-at-de-ri-oit, or Tale of the Lake, it appearing as

such appendage to Lake Champlain.

From the broad colonnade of the hotel the eye takes in the lake and its shores to the Narrows, about fifteen miles, and includes a theatre of great historic interest. Over those waters came the Hurons to fight the Mohawks, and during the Seven Years' war, when French dominion in America was crushed by the united powers of England and her American colonies, those hills often echoed the voice of the trumpet, the beat of the drum, the roar of cannon, the crack of musketry, the savage yell, and the shout of victory. At the head of the lake, British and Gallic warriors fought desperately, early in September, 1755; and history has recorded the results of many battle-fields in that vicinity during the last century, before and after the colonists and the mother-country came to blows, after a long and bitter quarrel. At the head of Lake George, where another fort had been erected near the ruins of William Henry, the republicans, in the old War for Independence, had a military depot; and until the surrender of Sir John Burgoyne, at Saratoga, on the Hudson, in 1777, that lake was a minor theatre of war, where the respective adherents of the "Continental" and "Ministerial" parties came into frequent collisions. Since then a profound peace has reigned over all that region, and at the Fort William Henry House and its neighbours are gathered every summer the wise and the wealthy, the noble, gay, and beautiful of many lands, seeking and finding health in recreation.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.