CHAPTER IV.

WE

started for Luzerne after an early dinner, crossing on our way the "French

field," whereon Dieskau disposed his troops for action. We then entered

the woods, and our route of eleven miles lay through a highly picturesque

country, partially cultivated, among the hills, and following the old Indian

war-path from the Sacandaga to Lake George. As we approached Luzerne, the

country spread into a high plain, as at Warrensburg, on the southern margin

of which, overlooked by lofty hills, lies Luzerne Lake. We passed it on our

left, and then went down quite a steep and winding way into the village, on

the bank of the Hudson, and found an excellent home at Rockwell's spacious

inn. We have seldom seen a village more picturesquely situated than this.

It is about seventy miles from the Adirondack village, and on the borders

of the great wilderness, where game and fish abound, and for a quiet place

of summer resort, can hardly be surpassed. It lies at the foot of a high bluff,

down which flows in cascades the outlet of Luzerne Lake, and leaps into the

Hudson, which here makes a magnificent sweep before rushing, in narrow channel

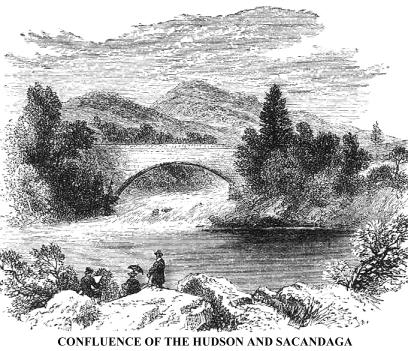

and foaming rapids between high rocky banks, to receive the equally turbulent

waters of the Sacandaga, just below. That place the Indians called Tio-sa-ron-da,

the "Meeting of the Waters." Twenty years ago, there were several

mills at the head of these falls: a flood swept them away, and they have never

been rebuilt.

WE

started for Luzerne after an early dinner, crossing on our way the "French

field," whereon Dieskau disposed his troops for action. We then entered

the woods, and our route of eleven miles lay through a highly picturesque

country, partially cultivated, among the hills, and following the old Indian

war-path from the Sacandaga to Lake George. As we approached Luzerne, the

country spread into a high plain, as at Warrensburg, on the southern margin

of which, overlooked by lofty hills, lies Luzerne Lake. We passed it on our

left, and then went down quite a steep and winding way into the village, on

the bank of the Hudson, and found an excellent home at Rockwell's spacious

inn. We have seldom seen a village more picturesquely situated than this.

It is about seventy miles from the Adirondack village, and on the borders

of the great wilderness, where game and fish abound, and for a quiet place

of summer resort, can hardly be surpassed. It lies at the foot of a high bluff,

down which flows in cascades the outlet of Luzerne Lake, and leaps into the

Hudson, which here makes a magnificent sweep before rushing, in narrow channel

and foaming rapids between high rocky banks, to receive the equally turbulent

waters of the Sacandaga, just below. That place the Indians called Tio-sa-ron-da,

the "Meeting of the Waters." Twenty years ago, there were several

mills at the head of these falls: a flood swept them away, and they have never

been rebuilt.

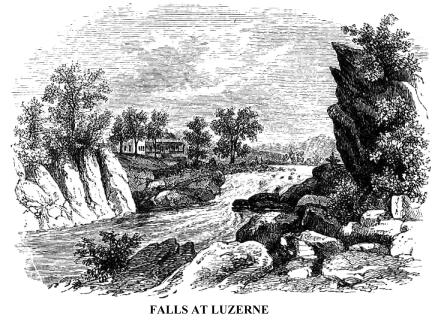

The rapids at Luzerne, which form a fall of about eighteen feet,

bear the name of Jesup's  Little

Falls, to distinguish them from Jesup's Great Falls five miles below, both

being included in patents granted to Ebenezer Jesup, who, with a family of

Fairchilds, settled there before the Revolution, when Luzerne was called Westfield.

These settlers espoused the cause of the king, and because of their depredations

upon their Whig neighbours, became very obnoxious. They held intercourse with

the loyal Scotch Highlanders, who were under the influence of the Johnsons

and other royalists in the Mohawk valley, and acted as spies and informants

for the enemies of republicanism. In the summer of 1777, while Burgoyne was

making his way toward Albany, Colonel St. Leger penetrated the upper Mohawk

valley, and laid siege to Fort Schuyler. On one occasion he sent Indian messengers

to the Fairchilds, who took the old trail through the Sacandaga valley, by

way of the Fish House, owned by Sir William Johnson. When they approached

Tio-sa-ron-da (Luzerne), they were discovered and pursued by a party

of republicans, and one of them, close pressed, leaped the Hudson, at the

foot of Jesup's Little Falls, the high wooded banks then approaching within

twenty-five feet of each other. He escaped, took the trail to Lake George,

and pushed on to Skenesborough (now Whitehall), where he found Burgoyne. Soon

after this a small party of republican troops, sent by General Gates, not

succeeding in capturing these royalists at Westfield, laid waste the settlement.

Little

Falls, to distinguish them from Jesup's Great Falls five miles below, both

being included in patents granted to Ebenezer Jesup, who, with a family of

Fairchilds, settled there before the Revolution, when Luzerne was called Westfield.

These settlers espoused the cause of the king, and because of their depredations

upon their Whig neighbours, became very obnoxious. They held intercourse with

the loyal Scotch Highlanders, who were under the influence of the Johnsons

and other royalists in the Mohawk valley, and acted as spies and informants

for the enemies of republicanism. In the summer of 1777, while Burgoyne was

making his way toward Albany, Colonel St. Leger penetrated the upper Mohawk

valley, and laid siege to Fort Schuyler. On one occasion he sent Indian messengers

to the Fairchilds, who took the old trail through the Sacandaga valley, by

way of the Fish House, owned by Sir William Johnson. When they approached

Tio-sa-ron-da (Luzerne), they were discovered and pursued by a party

of republicans, and one of them, close pressed, leaped the Hudson, at the

foot of Jesup's Little Falls, the high wooded banks then approaching within

twenty-five feet of each other. He escaped, took the trail to Lake George,

and pushed on to Skenesborough (now Whitehall), where he found Burgoyne. Soon

after this a small party of republican troops, sent by General Gates, not

succeeding in capturing these royalists at Westfield, laid waste the settlement.

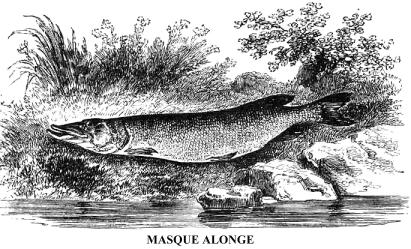

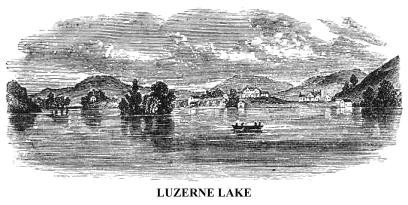

Luzerne

Lake, lying many feet above the village, is a beautiful little sheet of water,

with a single small island upon its bosom. It is the larger of a series of

four lakes, extending back to within five miles of Lake George. It abounds

with fine fish, the largest and most delicious being the Masque alonge,

a species of pike or pickerel, which is also found in the Upper Hudson, and

all over northern New York. One was caught in the lake, and brought to Rockwell's,

on the morning of our departure, which weighed between five and six pounds.*

Luzerne

Lake, lying many feet above the village, is a beautiful little sheet of water,

with a single small island upon its bosom. It is the larger of a series of

four lakes, extending back to within five miles of Lake George. It abounds

with fine fish, the largest and most delicious being the Masque alonge,

a species of pike or pickerel, which is also found in the Upper Hudson, and

all over northern New York. One was caught in the lake, and brought to Rockwell's,

on the morning of our departure, which weighed between five and six pounds.*

On the northern shore of Luzerne Lake, where the villas of

Benjamin C. Butler and J.  Leati,

Esqs. (seen in the picture), stood, was the ancient gathering place of the

Indians in council. Here was the fork of the great Sacandaga and Oneida trail,

one branch extending to Lake George and the northern country, and the other

to Fort Edward and the more southern country. All around the lake and village

are ranges of lofty hills, filled with iron ore. On the west is the Kayaderosseros

range, extending from Ballston to the Adirondacks, and on the east of the

Leati,

Esqs. (seen in the picture), stood, was the ancient gathering place of the

Indians in council. Here was the fork of the great Sacandaga and Oneida trail,

one branch extending to Lake George and the northern country, and the other

to Fort Edward and the more southern country. All around the lake and village

are ranges of lofty hills, filled with iron ore. On the west is the Kayaderosseros

range, extending from Ballston to the Adirondacks, and on the east of the

* The Masque alonge (Exor estor) (not sure of spelling, hard to read) derived its name from the peculiar formation of its mouth and head. The French called it Masque alonge, or Long-face. It is the largest of the pickerel species. Some have been caught among the Thousand Islands in the St. Lawrence, in the vicinity of Alexandria Bay, on its southern shore, weighing fifty pounds, and measuring five feet in length. It is the most voracious of fresh-water fish.

Luzerne range, stretching from Saratoga Springs to the western shores of Lake George. Four miles north of the village is a hemispherical mountain, eight hundred feet in height, rocky and bald, which the Indians called Se-non-ge-teah, the Great Upturned Pot.

The

Sacandaga is the largest tributary of the Mohawk, and comes down seventy-five

miles from the north-west, out of lakes and ponds in the wilderness of Hamilton

County. Its confluence with its receptacle is at the head of a very beautiful

valley, that terminates at Luzerne. It comes sweeping around the bases of

high hills with a rapid current, and rushes swiftly into the Hudson, where

the latter has become deep and sluggish after its commotion at the falls above.

Down that valley we rode, with the river in view all the way to the village

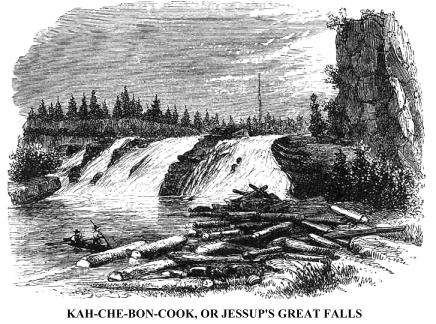

of Corinth, at the head of the long rapids above Jesup's Great Falls, the

Kah-che-bon-cook of the Indians. These were formerly known as the

Hadley Falls. They were afterward called Palmer's Falls, the land on each

side of the river being in possession of Beriah Palmer and others, who there

constructed extensive works

The

Sacandaga is the largest tributary of the Mohawk, and comes down seventy-five

miles from the north-west, out of lakes and ponds in the wilderness of Hamilton

County. Its confluence with its receptacle is at the head of a very beautiful

valley, that terminates at Luzerne. It comes sweeping around the bases of

high hills with a rapid current, and rushes swiftly into the Hudson, where

the latter has become deep and sluggish after its commotion at the falls above.

Down that valley we rode, with the river in view all the way to the village

of Corinth, at the head of the long rapids above Jesup's Great Falls, the

Kah-che-bon-cook of the Indians. These were formerly known as the

Hadley Falls. They were afterward called Palmer's Falls, the land on each

side of the river being in possession of Beriah Palmer and others, who there

constructed extensive works  for

manufacturing purposes. The water-power there, even at the very low stage

of the river, as when we visited it, has been estimated to be equal to fifteen

thousand horse-power. They had laid out a village, with a public square and

fountain, and were preparing for industrial operations far greater than at

any point so far up the Hudson. It is only sixteen miles north of Saratoga

Springs.

for

manufacturing purposes. The water-power there, even at the very low stage

of the river, as when we visited it, has been estimated to be equal to fifteen

thousand horse-power. They had laid out a village, with a public square and

fountain, and were preparing for industrial operations far greater than at

any point so far up the Hudson. It is only sixteen miles north of Saratoga

Springs.

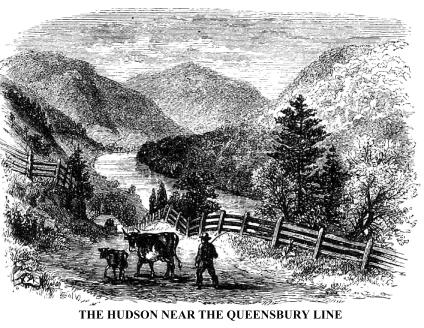

We followed a path down the margin of the roaring stream some distance, and, returning, took a rough road which led to the foot of the Great Fall. From Jesup's landing to this point, a distance of more than a mile, the river descends about one hundred and twenty feet, in some places rushing wildly through rocky gorges from eighty to one hundred feet in depth. The perpendicular fall is seventy-five feet. We did not see it in its grandeur, the river was so low. From its course back, some distance, the stream was choked with thousands of logs that had come down from the wilderness and lodged there. They lay in a mass, in every conceivable position, to the depth of many feet, and so filled the river as to form a safe, though rough bridge, for us to cross. Between this point and Glen's Falls, thirteen miles distant by the nearest road, the Hudson makes a grand sweep among lofty and rugged hills of the Luzerne range, and flows into a sandy plain a few miles above the latter village. We did not follow its course, but took that nearest road, for the day was waning. Over mountains and through valleys, catching glimpses of the river here and there, we traveled that bright afternoon in early autumn, our eyes resting only upon near objects most of the time, until we reached the summit of a lofty hill, nine miles from Glen's Falls. There a revelation of beauty, not easily described, burst upon the vision. Looking over and beyond the minor hills through an opening in the Luzerne range, we saw the Green Mountains of Vermont in the far distance, bathed in shadowy splendour, and all the intervening country, with its villages and farmhouses, lay before us. The spires and white houses of Glen's Falls appeared so near, that we anticipated a speedy end to our day's journey. That vision was enjoyed but for a few moments, for we were soon again among the tangled hills. But another appeared to charm us. We had just commenced the descent of a mountain, along whose brow lies the dividing line between the towns of Luzerne and Queensbury, when a sudden turn in the road revealed a deep, narrow valley far below us, with the Hudson sweeping through it with rapid current. The sun's last rays had left that valley, and the shadows were deepening along the waters as we descended to their margin. Twilight was drawing its delicate veil over the face of nature when we reached the plain just mentioned, and the night had closed in when we arrived at the village of Glen's Falls. We had hoped to reach there in time to visit the State Dam and the Great Boom, which span the Hudson at separate points, a few miles above the falls, but were compelled to forego that pleasure until morning.

We

were now fairly out of the wilderness in which the Hudson rises, and through

which it flows for a hundred miles; and here our little party was broken by

the departure of Mr. Buckingham for home. Mrs. Lossing and myself lingered

at Glen's Falls and at Fort Edward, five miles below, a day or two longer,

for the purpose of visiting objects of interest in their vicinity, a description

of which will be given as we proceed with our notes. A brief notice of the

State Dam and Great Boom, just mentioned, seems necessary.

We

were now fairly out of the wilderness in which the Hudson rises, and through

which it flows for a hundred miles; and here our little party was broken by

the departure of Mr. Buckingham for home. Mrs. Lossing and myself lingered

at Glen's Falls and at Fort Edward, five miles below, a day or two longer,

for the purpose of visiting objects of interest in their vicinity, a description

of which will be given as we proceed with our notes. A brief notice of the

State Dam and Great Boom, just mentioned, seems necessary.

The dam was about two and a- half miles above Glen's Falls.

It had been constructed about fifteen years before, to furnish water for the

feeder of the canal which connects the Hudson river and Lake Champlain. It

was sixteen hundred feet in length; and the mills near it have attracted a

population sufficient to constitute quite a village, named State Dam. About

two miles above this dyke was the Great Boom,  thrown

across the river for the purpose of catching all the logs that come floating

from above. It was made of heavy, hewn timbers, four of them bolted together

raft-wise. The ends of the groups were connected by chains, which worked over

friction rollers, to allow the boom to accommodate itself to the motion of

the water. Each end of the boom was secured to a heavy abutment by chains;

and above it were strong triangular structures to break the ice, to serve

as anchors for the boom, and to operate as shields to prevent the logs striking

the boom with the full speed of the current. At times, immense numbers of

logs were collected above this boom, filling the river for two or three miles.

In the spring of 1859, at least half a million of logs were collected there,

ready to be taken into small side-booms, assorted by the owners according

to their private marks, and sent down to Glen's Falls, Sandy Hill, or Fort

Edward, to be sawed into boards at the former places, or made into rafts at

the latter, for a voyage down the river. Heavy rains and melting snows filled

the river to overflowing. The great boom snapped asunder, and the half million

of logs went rushing down the stream, defying every barrier. The country below

was flooded by the swollen river; and we saw thousands of the logs scattered

over the valley of the Hudson from Fort Edward to Troy, a distance of about

forty miles.

thrown

across the river for the purpose of catching all the logs that come floating

from above. It was made of heavy, hewn timbers, four of them bolted together

raft-wise. The ends of the groups were connected by chains, which worked over

friction rollers, to allow the boom to accommodate itself to the motion of

the water. Each end of the boom was secured to a heavy abutment by chains;

and above it were strong triangular structures to break the ice, to serve

as anchors for the boom, and to operate as shields to prevent the logs striking

the boom with the full speed of the current. At times, immense numbers of

logs were collected above this boom, filling the river for two or three miles.

In the spring of 1859, at least half a million of logs were collected there,

ready to be taken into small side-booms, assorted by the owners according

to their private marks, and sent down to Glen's Falls, Sandy Hill, or Fort

Edward, to be sawed into boards at the former places, or made into rafts at

the latter, for a voyage down the river. Heavy rains and melting snows filled

the river to overflowing. The great boom snapped asunder, and the half million

of logs went rushing down the stream, defying every barrier. The country below

was flooded by the swollen river; and we saw thousands of the logs scattered

over the valley of the Hudson from Fort Edward to Troy, a distance of about

forty miles.

We have taken leave of the wilderness. Henceforth our path will be where the Hudson flows through cultivated plains, along the margins of gentle slopes, of rocky headlands, and of lofty hills; by the cottages of the humble, and the mansions of the wealthy; by pleasant hamlets, through thriving villages, ambitions cities, and the marts of trade and commerce.

Unlike the rivers of the elder world, famous in the history of men, the Hudson presents no grey and crumbling monuments of the ruder civilizations of the past, or even of the barbaric life so recently dwelling upon its borders. It can boast of no rude tower or mouldering wall, clustered with historical associations that have been gathering around them for centuries. It has no fine old castles, in glory or in ruins, with visions of romance pictured in their dim shadows; no splendid abbeys or cathedrals, in grandeur or decay, from which emanate an aura of religious memories. Nor can it boast of mansions or ancestral halls wherein a line of heroes have been born, or illustrious families have lived and died, generation after generation. Upon its banks not a vestige of feudal power may be seen, because no citadel of great wrongs ever rested there. The dead Past has left scarcely a record upon its shores. It is full of the living Present, illustrating by its general aspect the free thought and free action which are giving strength and solidity to the young and vigorous nation within whose bosom its bright waters flow.

Yet the Hudson is not without a history--a history brilliant in some respects, and in all interesting, not only to the American, but to the whole civilized world. From the spot where we now stand--the turbulent Glen's Falls--to the sea, the banks of the beautiful river have voices innumerable for the ear of the patient listener; telling of joy and woe, of love and beauty, of noble heroism, and more noble fortitude, of glory, and high renown, worthy of the sweetest cadences of the minstrel, the glowing numbers of the poet, the deepest investigations of the philosopher, and the gravest records of the historian. Let us listen to those voices.

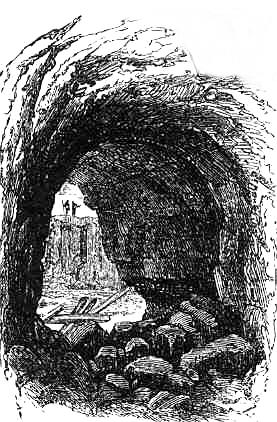

Glen's Falls consist of a series of rapids and cascades, along a descent of about eighty feet, the water flowing over ragged masses of black marble, which here form the bed and banks of the river. Hawk-eye, in Cooper's "Last of the Mohicans," has given an admirable description of these falls, as they appeared before the works of man changed their features. He is standing in a cavern, or irregular arched way, in the rock below the bridge.* in the time of the old French war, with Uncas and Major Heywood, and Cora and Alice Munro, the daughters of the commandant at Fort William Henry, on Lake George, when Montcalm with his motley horde of French and Indians was approaching. "Ay," he said, "there are the falls on two sides of us, and the river above and below. If you had daylight, it would be worth the trouble to step up on the height of this rock, and look at the perversity of the water. It falls by no rule at all: sometimes it leaps, sometimes it tumbles; there it skips--here it shoots; in one place 'tis as white as snow, and in another' tis as green as grass; hereabouts, it pitches into deep hollows, that rumble and quake the 'arth, and thereaway it ripples and sings like a brook, fashioning whirlpools and gullies in the old stone, as if 'twere no harder than trodden clay. The whole design of the river seems disconcerted. First, it runs smoothly, as if meaning to go down the descent as things were ordered; then it angles about and faces the shores; nor are there places wanting where it looks backward, as if unwilling to leave the wilderness to mingle with the salt!"

* A view of this cavern is seen at the head of this chapter. The spectator is supposed to be within it, and looking out upon the river and the opposite bank.

The falls had few of these features when we visited them. The volume of water was so small that the stream was almost hidden in the deep channels in the rock worn by the current during the lapse of centuries. No picture could then be made to give an adequate idea of the cascades when the river is full, and I contented myself with making a sketch of the scene below the bridge, at the foot of the falls, from the water-side entrance to the cavern alluded to. A fine sepia drawing, by the late Mr. Bartlett, which I found subsequently among some original sketches in my possession, supplies the omission. The engraving from it gives a perfect idea of the appearance of the falls when the river is at its usual height.

The Indians gave this place the significant name of Che-pon-tuc-- meaning a difficult place to get around. The white man first called the cascades Wing's Falls, in honour of Abraham Wing, who, with others from Duchess County, New York, settled there under a grant from the Crown, about the middle of the last century. Many years afterwards, when Wing was dead, and his son was in possession of the falls and the adjacent lands, a convivial party assembled at table in the tavern there, which formed the germ of the present village of nearly four thousand inhabitants. Among them was Mr. Wing; also John Glen, a man of fortune, who lived on the south side of the river. The wine circulated freely, and it ruled the wit of the hour. Under its influence, Wing agreed to transfer to Glen the right of name to the falls, on condition that the latter should pay for the supper of the company. Glen immediately posted handbills along the bridle-path from the Wing's to Schenectada and Albany, announcing the change in the name of the falls; and ever since they have been known as Glen's Falls. For a "mess of pottage" the young man sold his family birthright to immortality.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.