CHAPTER FIVE, Part TWO

The leadership of that invasion from the North was entrusted to Lieutenant-General Sir John Burgoyne, who had won military laurels in Portugal, had held a seat in the king's council, and was then a member of Parliament. He arrived at Quebec in March, 1777, and in June had collected a large force of English and German troops, Canadians, and Indians, at the foot of Lake Champlain. At the beginning of July he invested Ticonderoga with ten thousand men, drove the Americans from that old fortress and its dependencies, and, as we have observed, swept victoriously up the lake to Skenesborough, and advanced to Fort Edward. From that point he sent a detachment to Bennington, in Vermont, to seize cattle and provisions for the use of the army. The expedition was defeated by militia, under Stark, and thereby Burgoyne received a blow from which he did not recover. Yet he moved forward, crossed the Hudson a little above Schuylerville, and pitched his tents, and formed a fortified camp upon the site of that village. He had stated at Fort Edward that he should eat his Christmas dinner in Albany, a laurelled conqueror, with the great objects of the campaign perfectly accomplished; but now he began to doubt.

General Schuyler had been the commander of the troops opposed to Burgoyne until the 19th of August, when he surrendered his charge to General Gates, a conceited officer, very much his inferior in every particular. This supersedure had been accomplished by political intrigue.

When Burgoyne crossed the Hudson, Gates, then at the mouth of the Mohawk, advanced with his troops to Bemis's Height, about twelve miles below the halting British army, and there established a fortified camp. Perceiving the necessity of immediate hostile action--because the Republican army was hourly augmenting (volunteers flocking in from all quarters, and particularly from New England)--Burgoyne crossed the Fish Creek, burned the mills and mansion of General Schuyler, and advanced upon Gates.

A severe but indecisive battle was fought at Bemis's Heights on the 19th of September; Burgoyne fell back a few miles toward his entrenched camp, and resolved there to await the expected approach of Sir Henry Clinton, with a large force, up the lower Hudson. Clinton was tardy, perils were thickening, and Burgoyne resolved to make another attack upon Gates. After a severe battle fought on the 7th of October, upon almost the same ground occupied in the engagement on the 19th of September, he was again compelled to fall back. He finally retreated to his entrenched camp beyond the Fish Creek.

Burgoyne's force was now hourly diminishing, the Canadians and Indians deserting him in great numbers, while volunteers were swelling the ranks of Gates. The latter now advanced upon Burgoyne, and, on the 17th of October, that general surrendered his army of almost six thousand men, and all its appointments, into the hands of the Republicans. The forts upon Lakes George and Champlain were immediately abandoned by the British, and the Republicans held an unobstructed passage from the Hudson Highlands to St. John, on the Sorel, in Canada.

The spot where Burgoyne's army laid down their arms is upon the plain in front of Schuylerville, near the site of old Fort Hardy, a little north of the highway leading from the village across the Hudson, over the long bridge already mentioned. Our view is taken from one of the canal bridges, looking north-east. The Hudson is seen beyond the place of surrender, and in the more remote distance may be observed the conical hills which, on the previous day, had swarmed with American volunteers.

With

the delicate courtesy of a gentleman, General Gates ordered all his army within

his camp, that the vanquished might not be submitted to the mortification

of their gaze at the moment of the great humiliation. The two generals had

not yet seen each other. As soon as the troops had laid down their arms, Burgoyne

and his officers proceeded towards Gates's camp, to be introduced. They crossed

the Fish Creek at the head of the rapids, and proceeded towards the republican

general's quarters, about a mile and a-half down the river. Burgoyne led the

way, with Kingston (his adjutant-general), and his aides-de-camp, Captain

Lord Petersham and Lieutenant Wilford, followed by Generals Phillips, Reidesel,

and Hamilton, and other officers, according to rank. General Gates, informed

of the approach of Burgoyne, went out with his staff to meet him at the head

of his camp. Burgoyne, was dressed in a rich uniform of scarlet and gold,

and Gates in a plain blue frock coat. When within about a sword's length of

each other, they reined up their horses, and halted. Colonel Wilkinson, Gates's

aide-de-camp, then introduced the two generals. Both dismounted, and Burgoyne,

raising his hat gracefully, said--"The fortune of war, General Gates,

has made me your prisoner." The victor promptly replied--"I shall

always be ready to bear testimony that it has not been through any fault of

your excellency." The other officers were then introduced in turn, and

the whole party repaired to Gates's head-quarters, where the best dinner that

could be procured was served.

With

the delicate courtesy of a gentleman, General Gates ordered all his army within

his camp, that the vanquished might not be submitted to the mortification

of their gaze at the moment of the great humiliation. The two generals had

not yet seen each other. As soon as the troops had laid down their arms, Burgoyne

and his officers proceeded towards Gates's camp, to be introduced. They crossed

the Fish Creek at the head of the rapids, and proceeded towards the republican

general's quarters, about a mile and a-half down the river. Burgoyne led the

way, with Kingston (his adjutant-general), and his aides-de-camp, Captain

Lord Petersham and Lieutenant Wilford, followed by Generals Phillips, Reidesel,

and Hamilton, and other officers, according to rank. General Gates, informed

of the approach of Burgoyne, went out with his staff to meet him at the head

of his camp. Burgoyne, was dressed in a rich uniform of scarlet and gold,

and Gates in a plain blue frock coat. When within about a sword's length of

each other, they reined up their horses, and halted. Colonel Wilkinson, Gates's

aide-de-camp, then introduced the two generals. Both dismounted, and Burgoyne,

raising his hat gracefully, said--"The fortune of war, General Gates,

has made me your prisoner." The victor promptly replied--"I shall

always be ready to bear testimony that it has not been through any fault of

your excellency." The other officers were then introduced in turn, and

the whole party repaired to Gates's head-quarters, where the best dinner that

could be procured was served.

The plain farmhouse in which that remarkable dinner-party was

assembled remained unaltered externally  when

we visited it, excepting such changes as have been effected by necessary repairs.

It stood about eighty rods from the Hudson, on the western margin of the plain;

and between it and the river the Champlain Canal passed. Our sketch was made

from the highway, and includes glimpses of the canal, the river, and the hills

on the eastern side of the plain.

when

we visited it, excepting such changes as have been effected by necessary repairs.

It stood about eighty rods from the Hudson, on the western margin of the plain;

and between it and the river the Champlain Canal passed. Our sketch was made

from the highway, and includes glimpses of the canal, the river, and the hills

on the eastern side of the plain.

The Baroness Reidesel, in her narrative of these events, says: "I was, I confess, afraid to go over to the enemy, as it was quite a new situation to me. When I drew near the tents, a handsome man approached and met me, took my children from the caleche, and hugged and kissed them, which affected me almost to tears. 'You tremble,' said he, addressing himself to me; 'be not afraid.' 'No,' I answered, 'you seem so kind and tender to my children, it inspires me with courage.' He now led me to the tent of General Gates, where I found Generals Burgoyne and Phillips, who were on a friendly footing with the former.

"All the generals remained to dine with General Gates. The same gentleman who received me so kindly, now came and said to me, 'You will be very much embarrassed to eat with all those gentlemen; come with your children to my tent, where I will prepare for you a frugal dinner, and give it with a free will.' I said, 'You are certainly a husband and a father, you have shown me so much kindness.' I now found that he was General Schuyler. He treated me with excellent smoked tongue, beef-steaks, potatoes, and good bread and butter. Never could I have wished to eat a better dinner. I was content; I saw all around me were so likewise. When we had dined, he told me his residence was at Albany, and that General Burgoyne intended to honour him as his guest, and invited myself and children to do so likewise. I asked my husband how I should act; he told me to accept the invitation." General Schuyler's house at Albany yet remains, and there we shall hereafter meet the Baroness and Burgoyne, as guests of that truly noble republican.

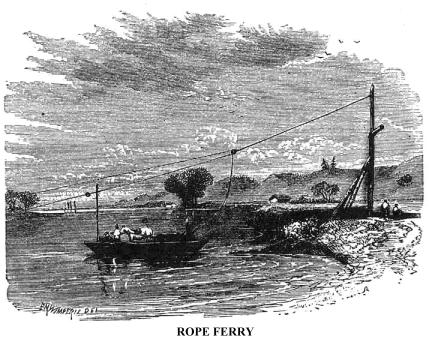

The Hudson, from Schuylerville to Stillwater, a distance of about thirteen miles, flows through a rich plain, and its course is unbroken by island, rapid, or bridge. Between it and the western margin of the plain is the Champlain Canal, bearing upon its quiet bosom the wealth of a large internal commerce, extending from New York and Albany to Canada. It was spanned, for the convenience of the farmers through whose land it passes, with numerous bridges, stiff and ungraceful in appearance, and all of the same model. A picture of one of them is given at the head of this chapter. The river was also crossed in several places by means of rope ferries. These, at times, presented quite picturesque scenes, when men and women, teams, live stock, and merchandize, happen to constitute the freight at one time. The vehicle was a large scow or batteau, which was pushed by means of long poles, that reached to the bottom of the river; and it was kept in its course, in defiance of the current, by ropes fore and aft, attached by friction rollers to a stout cable stretched across the stream. There were several of these ferries between Fort Edward and Stillwater, the one most used being that at Bemis's Heights, of which we give a drawing.

Three

miles below Schuylerville, on the same side of the river, is the hamlet of

Coveville, formerly called Do-ve-gat, or Van Vechten's Cove. It is a pretty,

quiet little place, and sheltered by hills in the rear; the inhabitants are

chiefly agriculturists, and the families of those employed in canal navigation.

Here Burgoyne halted, and encamped for two days, after leaving his entrenched

camp to confront Gates, while a working party repaired the roads and bridges

in advance to Wilbur's Basin, three miles below. He then advanced, and pitched

his tents at the latter place, upon the narrow plain between the river and

the hills, and upon the slopes. Here he also encamped on the morning after

the first battle at Bemis's Heights, the opening of a cloudy, dull, and cheerless

day, that harmonized with the feelings of the British commander. He felt convinced

that, without the aid of General Clinton's co-operation in drawing off a part

of the republican army to the defence of the country below, he should not

be able to advance. Yet he wrought diligently in strengthening his position.

He erected four

Three

miles below Schuylerville, on the same side of the river, is the hamlet of

Coveville, formerly called Do-ve-gat, or Van Vechten's Cove. It is a pretty,

quiet little place, and sheltered by hills in the rear; the inhabitants are

chiefly agriculturists, and the families of those employed in canal navigation.

Here Burgoyne halted, and encamped for two days, after leaving his entrenched

camp to confront Gates, while a working party repaired the roads and bridges

in advance to Wilbur's Basin, three miles below. He then advanced, and pitched

his tents at the latter place, upon the narrow plain between the river and

the hills, and upon the slopes. Here he also encamped on the morning after

the first battle at Bemis's Heights, the opening of a cloudy, dull, and cheerless

day, that harmonized with the feelings of the British commander. He felt convinced

that, without the aid of General Clinton's co-operation in drawing off a part

of the republican army to the defence of the country below, he should not

be able to advance. Yet he wrought diligently in strengthening his position.

He erected four  redoubts,

one upon each of four hills, two above and two below Wilbur's Basin, and made

lines of entrenchments from them to the river, covering each with a battery.

From this camp he marched to battle on the 7th of October, and in that engagement

lost his gallant friend, General Simon Fraser, who, at the head of five hundred

picked men, was the directing spirit of the British troops in action. This

was perceived by the American commanders, for Fraser's skill and courage were

everywhere conspicuous. When the lines gave way, he brought order out of confusion;

when regiments began to waver, he infused courage into them by voice and example.

He was mounted upon a splendid iron-grey gelding, and dressed in the full

uniform of a field officer. He was thus made a conspicuous object for the

mark of the Americans.

redoubts,

one upon each of four hills, two above and two below Wilbur's Basin, and made

lines of entrenchments from them to the river, covering each with a battery.

From this camp he marched to battle on the 7th of October, and in that engagement

lost his gallant friend, General Simon Fraser, who, at the head of five hundred

picked men, was the directing spirit of the British troops in action. This

was perceived by the American commanders, for Fraser's skill and courage were

everywhere conspicuous. When the lines gave way, he brought order out of confusion;

when regiments began to waver, he infused courage into them by voice and example.

He was mounted upon a splendid iron-grey gelding, and dressed in the full

uniform of a field officer. He was thus made a conspicuous object for the

mark of the Americans.

It

was evident that the fate of the battle depended upon General Fraser, and

this the keen eye and quick judgment of Colonel Morgan, commander of a rifle

corps from the south, perceived. A thought flashed through his brain, and

in an instant he prepared to execute a deadly purpose. Calling a file of his

best men around him, he said, as he pointed toward the British right wing,

which was making its way victoriously,--"That gallant officer is General

Fraser; I admire and honour him, but it is necessary he should die; victory

for the enemy depends upon him. Take your stations in that clump of bushes,

and do your duty." Within five minutes after this order was given, General

Fraser fell, and was carried from the field by two grenadiers. His aide-de-camp

had just observed that the general was a particular mark for the enemy, and

said,--"Would it not be prudent for you to retire from this place?"

Fraser replied, "My duty forbids me to fly from danger," and the

next moment he fell.

It

was evident that the fate of the battle depended upon General Fraser, and

this the keen eye and quick judgment of Colonel Morgan, commander of a rifle

corps from the south, perceived. A thought flashed through his brain, and

in an instant he prepared to execute a deadly purpose. Calling a file of his

best men around him, he said, as he pointed toward the British right wing,

which was making its way victoriously,--"That gallant officer is General

Fraser; I admire and honour him, but it is necessary he should die; victory

for the enemy depends upon him. Take your stations in that clump of bushes,

and do your duty." Within five minutes after this order was given, General

Fraser fell, and was carried from the field by two grenadiers. His aide-de-camp

had just observed that the general was a particular mark for the enemy, and

said,--"Would it not be prudent for you to retire from this place?"

Fraser replied, "My duty forbids me to fly from danger," and the

next moment he fell.

About half way between Wilbur's Basin and Bemis's, stood, until within twenty years, a rude building, the upper half somewhat projecting, and every side of it battered and pierced by bullets. It was used by Burgoyne as his quarters when he first moved forward to attack Gates, and there the Baron Reidesel had his quarters at the time of the battle of the 7th of October. Thither the wounded Fraser was conveyed by his grenadiers, and consigned to the care of the wife of the Brunswick general.

"About four o'clock in the afternoon," says the baroness,

"instead of the guests [Burgoyne and Phillips]  whom

I expected to dinner, General Fraser was brought on a litter mortally wounded.

The table, which was already set, was instantly removed, and a bed placed

in its stead for the wounded general. He said to the surgeon, 'Tell me if

my wound is mortal; do not flatter me.' The ball had passed through his body,

and, unhappily for the general, he had eaten a very hearty breakfast, by which

the stomach was distended, and the ball, as the surgeon said, had passed through

it. I often heard him exclaim, with a sigh, 'O fatal ambition! Poor General

Burgoyne! O my dear wife!' He was asked if he had any request to make, to

which he replied, that, if General Burgoyne would permit it, he should like

to be buried at six o'clock in the evening, on the top of a mount, in a redoubt

which had been built there."

whom

I expected to dinner, General Fraser was brought on a litter mortally wounded.

The table, which was already set, was instantly removed, and a bed placed

in its stead for the wounded general. He said to the surgeon, 'Tell me if

my wound is mortal; do not flatter me.' The ball had passed through his body,

and, unhappily for the general, he had eaten a very hearty breakfast, by which

the stomach was distended, and the ball, as the surgeon said, had passed through

it. I often heard him exclaim, with a sigh, 'O fatal ambition! Poor General

Burgoyne! O my dear wife!' He was asked if he had any request to make, to

which he replied, that, if General Burgoyne would permit it, he should like

to be buried at six o'clock in the evening, on the top of a mount, in a redoubt

which had been built there."

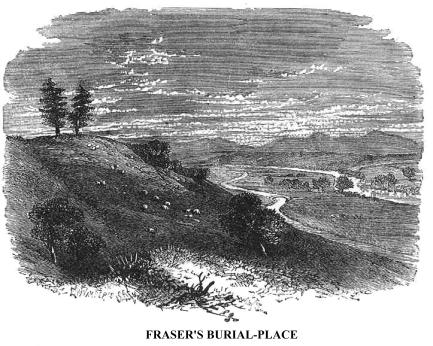

General

Fraser died at eight o'clock the following morning, and was buried in the

redoubt upon the hill at six o'clock that evening, according to his desire*

It was just at sunset, on a mild October evening, when the funeral procession

moved slowly up the hill, bearing the body of the gallant dead. It was composed

of only the members of his own military family, the commanding generals, and

Mr. Brudenell, the chaplain; yet the eyes of hundreds of both armies gazed

upon the scene. The Americans, ignorant of the true character of the procession,

kept up a constant cannonade upon the redoubt, toward which it was moving.

Undismayed, the companions of Fraser buried him just as the evening shadows

came on. Before the impressive burial services of the Anglican Church were

ended, the irregular firing ceased, and the solemn voice of a single canon,

at measured intervals, boomed along the valley, and awakened responses from

the hills. It was a minute-gun, fired by the Americans in honour of the accomplished

soldier. When information reached the Republicans that the gathering at the

redoubt was a funeral company, fulfilling the wishes of a brave officer, the

cannonade with balls instantly ceased.

General

Fraser died at eight o'clock the following morning, and was buried in the

redoubt upon the hill at six o'clock that evening, according to his desire*

It was just at sunset, on a mild October evening, when the funeral procession

moved slowly up the hill, bearing the body of the gallant dead. It was composed

of only the members of his own military family, the commanding generals, and

Mr. Brudenell, the chaplain; yet the eyes of hundreds of both armies gazed

upon the scene. The Americans, ignorant of the true character of the procession,

kept up a constant cannonade upon the redoubt, toward which it was moving.

Undismayed, the companions of Fraser buried him just as the evening shadows

came on. Before the impressive burial services of the Anglican Church were

ended, the irregular firing ceased, and the solemn voice of a single canon,

at measured intervals, boomed along the valley, and awakened responses from

the hills. It was a minute-gun, fired by the Americans in honour of the accomplished

soldier. When information reached the Republicans that the gathering at the

redoubt was a funeral company, fulfilling the wishes of a brave officer, the

cannonade with balls instantly ceased.

Other gallant British officers were severely wounded on that day; one of these was the accomplished Major Ackland, of the grenadiers, who was accompanied in the campaign by his charming wife, the Lady Harriet, fifth daughter of Stephen, first Earl of Ilchester, and great-grandmother of the present Earl of Carnarvon. He was shot through both legs, and conveyed to the house of Mr. Neilson, upon Bemis's Heights, within the American lines.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.