CHAPTER VII.

he grounds around Van Rensselaer Manor House extend from Broadway to the river,

and embrace a large garden and conservatory. There in the midst of rural scenery,

the sounds of a swift-running brook, and almost the quietude of a sylvan retreat,

the "lord of the manor of Rensselaerwyek," the lineal descendant

of Killian, the pearl merchant, and first Patroon, was living when our sketch

was made in elegant but unostentatious style--a simple Republican, without

the feudal title of his progenitors, except by courtesy. Within the mansion

are collected some exquisite works of Art, and family portraits extending

in regular order back to the first Patroon. At the head of the great staircase

leading from the spacious hall to the chambers was a portion of the illuminated

window which, for one hundred and ninety years, occupied a place in the old

Dutch Church that stood in the middle of State Street, at its intersection

by Broadway. It bears the arms of the Van Rensselaer family, which were placed

in the church by the son of Killian.

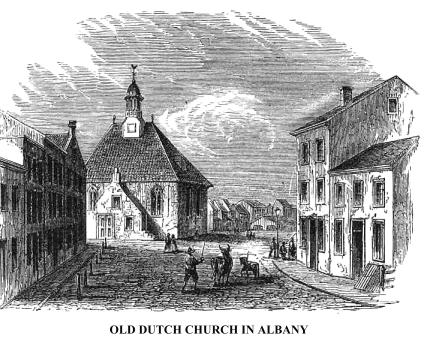

That old church, a sketch of which, with the appearance of

the neighbourhood at the time of its demolition  in

1805, is seen in our picture, was a curiously arranged place of worship. It

was built of stone, in 1715, over a smaller one erected in 1656, in which

the congregation continued to worship, until the new one was roofed. There

was an interruption in the stated worship for only three Sabbaths. It had

a low gallery, and the huge stove used in heating the building was placed

upon a platform so high, that the sexton went upon it from the gallery to

kindle the fire, implying a belief in those days that heated air descended,

instead of ascending, as we are now taught by the philosophers. The pulpit

was made of carved oak, octagonal in form, and in front of it was a bracket,

on which the minister placed his hour-glass, when he commenced preaching.

From the pulpit shone in succession those lights of the Reformed Dutch Church

in America, Dominies Schaats, Delius, the land speculator, Lydius, Vandriéssen,

Van Schie, Frelinghuysen, Westerlo, and Johnson. And from it the

in

1805, is seen in our picture, was a curiously arranged place of worship. It

was built of stone, in 1715, over a smaller one erected in 1656, in which

the congregation continued to worship, until the new one was roofed. There

was an interruption in the stated worship for only three Sabbaths. It had

a low gallery, and the huge stove used in heating the building was placed

upon a platform so high, that the sexton went upon it from the gallery to

kindle the fire, implying a belief in those days that heated air descended,

instead of ascending, as we are now taught by the philosophers. The pulpit

was made of carved oak, octagonal in form, and in front of it was a bracket,

on which the minister placed his hour-glass, when he commenced preaching.

From the pulpit shone in succession those lights of the Reformed Dutch Church

in America, Dominies Schaats, Delius, the land speculator, Lydius, Vandriéssen,

Van Schie, Frelinghuysen, Westerlo, and Johnson. And from it the  Gospel

is still preached in Albany. With its bracket, it occupies a place in the

North Dutch Church, in that city.

Gospel

is still preached in Albany. With its bracket, it occupies a place in the

North Dutch Church, in that city.

The bell-rope of the old church hung down in the centre of the building, and upon that cord tradition has suspended many a tale of trouble for Mynheer Brower, one of its sextons, who lived in North Pearl Street. He went to the church every night at eight o'clock, pursuant to orders, to ring the "suppawn bell." This was the signal for the inhabitants to eat their "suppawn," or hasty-pudding, and prepare for bed. It was equivalent in its office to the old English curfew bell. On these occasions the wicked boys would sometimes tease the old bell-ringer. They would slip stealthily into the church while he was there with his dim lantern, unlock the side door, hide in some dark corner, and when the old man was fairly seated at home, and had his pipe lighted for a last smoke, they would ring the bell furiously. Down to the old church the sexton would hasten, the boys would slip out at the side door before his arrival, and the old man would return home thoughtfully, musing upon the probability of invisible hands pulling at his bell-rope--those

"People--ah, the people,

They that dwell up in the steeple

All alone.

And who, tolling, tolling, tolling,

In that muffled monotone,

Feel a glory in so rolling

On the human heart a stone;

They are neither man nor woman,

They are neither brute nor human,

They are ghouls!"

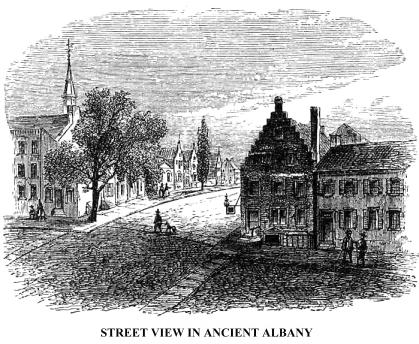

Albany were a quaint aspect until the beginning of the present century, on account of the predominance of steep-roofed houses, with their terraced gables to the street. A fair specimen is given in our Street View in Ancient Albany, which shows the appearance of the town at the intersection of North Pearl and State Streets, sixty years ago. The house at the nearer corner was built as a parsonage for the Rev. Gideon Schaats, who arrived in Albany in 1652. The materials were imported from Holland,--bricks, tiles, iron, and wood-work,--and were brought, with the church bell and pulpit, in 1657. "When I was quite a lad," says a late writer, "I visited the house with my mother, who was acquainted with the father of Balthazar Lydius, the last proprietor of the mansion. To my eyes it appeared like a palace, and I thought the pewter plates in a corner cupboard were solid silver, they glittered so. The partitions were made of mahogany, and the exposed beams were ornamented with carvings in high relief, representing the vine and fruit of the grape. To show the relief more perfectly, the beams were painted white. Balthazar was an eccentric old bachelor, and was the terror of all the boys. Strange stories, almost as dreadful as those which cluster around the name of Bluebeard, were told of his fierceness on some occasions; and the urchins, when they saw him in the streets, would give him the whole side-walk, for he made them think of the ogre, growling out his

'Fee, fo, fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman

He was a tall, spare Dutchman, with a bullet head, sprinkled

with thin white hair in his latter years. He was  fond

of his pipe and his bottle, and gloried in his celibacy, until his life was

'in the sere and yellow leaf.' Then he gave a pint of gin for a squaw (an

Indian woman), and calling her his wife, lived with her as such until his

death."

fond

of his pipe and his bottle, and gloried in his celibacy, until his life was

'in the sere and yellow leaf.' Then he gave a pint of gin for a squaw (an

Indian woman), and calling her his wife, lived with her as such until his

death."

On the opposite corner was seen an elm-tree, yet standing in 1860, but of statelier proportions, which was planted more than a hundred years before by Philip Livingston, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, whose dwelling was next to the corner. It was a monument to the planter, more truly valued of the Albanians in the heats of summer, than would be the costliest pile of brass or marble.

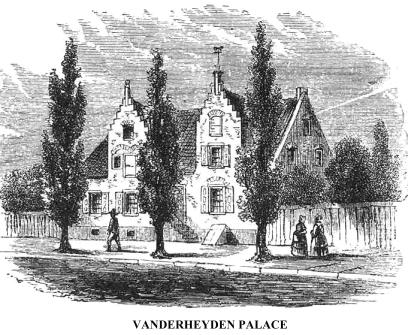

Further up the street is seen a large building, with two gables,

which was known as the Vanderheyden Palace. It is a good specimen of the external

appearance of the better class of houses erected by the Dutch in Albany. It

was built in 1725, by Johannes Beckman, one of  the

old burghers of that city; and was purchased, in 1778, by one of the Vanderheydens

of Troy, who, for many years, lived there in the style of the old Dutch aristocracy.

On account of its size, it was dignified with the title of palace. It figures

in Washington Irving's story of Dolph Heyliger, in "Bracebridge Hall,"

as the residence of Heer Anthony Vanderheyden; and when Mr. Irving transformed

the old farmhouse of Van Tassel into his elegant Dutch cottage at "Sunnyside,"

he made the southern gable an exact imitation of that of the palace in Albany.

And the iron vane, in the form of a horse at full speed, that turned for a

century upon one of the gables of the Vanderheyden Palace, now occupies the

peak of that southern gable at delightful "Sunnyside."

the

old burghers of that city; and was purchased, in 1778, by one of the Vanderheydens

of Troy, who, for many years, lived there in the style of the old Dutch aristocracy.

On account of its size, it was dignified with the title of palace. It figures

in Washington Irving's story of Dolph Heyliger, in "Bracebridge Hall,"

as the residence of Heer Anthony Vanderheyden; and when Mr. Irving transformed

the old farmhouse of Van Tassel into his elegant Dutch cottage at "Sunnyside,"

he made the southern gable an exact imitation of that of the palace in Albany.

And the iron vane, in the form of a horse at full speed, that turned for a

century upon one of the gables of the Vanderheyden Palace, now occupies the

peak of that southern gable at delightful "Sunnyside."

Kalm, the Swedish traveler, who visited Albany in 1748 and 1749, says in his Journal,--"The houses in this town are very neat, and partly built with stones, covered with shingles of the white pine. Some are slated with tiles from Holland. Most of the houses are built in the old way, with the gable-end toward the street; a few excepted, which were lately built in the manner now used..... The gutters on the roofs reach almost to the middle of the street. This preserves the walls from being damaged by the rain, but it is extremely disagreeable in rainy weather for the people in the streets, there being hardly any means for avoiding the water from the gutters. The street doors are generally in the middle of the houses, and on both sides are seats, on which, during fair weather, the people spend almost the whole day, especially on those which are in the shadow of the houses. In the evening these seats are covered with people of both sexes; but this is rather troublesome, as those who pass by are obliged to greet everybody, unless they will shock the politeness of the inhabitants of the town."

Kalm appears to have had some unpleasant experiences in Albany, and in his Journal gave his opinion very freely concerning the inhabitants. "The avarice and selfishness of the inhabitants of Albany," he says, "are very well known throughout all North America. If a Jew, who understands the art of getting forward perfectly well, should settle amongst them, they would not fail to ruin him; for this reason, no one comes to this place without the most pressing necessity." He complains that he "was obliged to pay for everything twice, thrice, and four times as dear as in any other part of North America" which he had passed through. If he wanted any help, he had to pay "exorbitant prices for their services," and yet he says he found some exceptions among them. After due reflection, he came to the following conclusion respecting "the origin of the inhabitants of Albany and its neighbourhood. Whilst the Dutch possessed this country, and intended to people it, the government took up a pack of vagabonds, of which they intended to clear the country, and sent them, along with a number of other settlers, to this province. The vagabonds were sent far from the other colonists, upon the borders toward the Indians and other enemies; and a few honest families were persuaded to go with them, in order to keep them in bounds. I cannot in any other way account for the difference between the inhabitants of Albany and the other descendants of so respectable a nation as the Dutch."

Albany was settled by the Dutch, and is the oldest of the permanent

European settlements in the United States. Hudson passed its site in the Half-Moon,

in the early autumn of 1609; and the next year Dutch navigators built trading-houses

there, to traffic for furs with the Indians. In 1614 they erected a stockade

fort on an island near. It was swept away by a spring freshet in 1617. Another

was built on the main: it was abandoned in 1623, and a stronger one erected

in what is now Broadway, below State Street. This was furnished with eight

cannon loaded with stones, and was named Fort Orange, in honour of the then

Stadtholder of Holland. Down to the period of the intercolonial wars, the

settlement and the city were  known

as Fort Orange by the French in Canada. Families settled there in 1630, and

for awhile the place was called Beverwyck. When James, Duke of York and Albany

(brother to Charles II.), came into possession of New Netherland, New Amsterdam

was named New York, and Orange, or Beverwyck, was called Albany.

known

as Fort Orange by the French in Canada. Families settled there in 1630, and

for awhile the place was called Beverwyck. When James, Duke of York and Albany

(brother to Charles II.), came into possession of New Netherland, New Amsterdam

was named New York, and Orange, or Beverwyck, was called Albany.

In 1647 a fort, named Williamstadt, was erected upon the hill at the head of State Street, very near the site of the State Capitol, and the city was enclosed by a line of defences in septangular form. In 1683 the little trading post, having grown first to a hamlet and then to a large village, was incorporated a city, and Peter Schuyler, already mentioned (son of the first of that name who came to America), was chosen its first mayor. Out of the manor of Rensselaerwyck a strip of land, a mile wide, extending from the Hudson at the town, thirteen miles back, was granted to the city, but the title to all the remainder of the soil of that broad domain was confirmed to the Patroon. When, toward the middle of the last century, the province was menaced by the French and Indians, a strong quadrangular fort, built of stone, was erected upon the site of that of Williamstadt. Within the heavy walls, which had strong bastions at the four corners, was a stone building for the officers and soldiers. It was named Fort Frederick; but its situation was so insecure, owing to higher hills in the rear, from which an enemy might attack it, it was not regarded as of much value by Abererombie and others during the campaigns of the Seven Years' War. From that period until the present, Albany has been growing more and more cosmopolitan in its population, until now very little of the old Dutch element is distinctly perceived. The style of its architecture is changed, and very few of the buildings erected in the last century and before, are remaining.

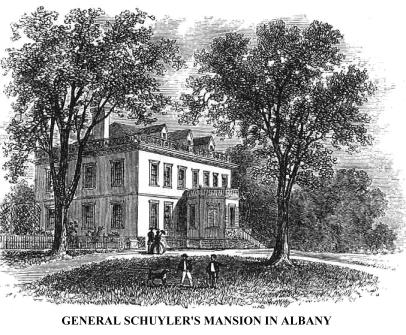

Among the most interesting of these relies of the past is the mansion erected by General Philip Schuyler, at about the time when the Van Rensselaer Manor House was built. It stands in the southern part of the city, at the head of Schuyler Street, and is a very fine specimen of the domestic architecture of the country at that period. It is entered at the front by an octagonal vestibule, richly ornamented within. The rooms are spacious, with high ceilings, and wainscoted. The chimney-pieces in some of the rooms are finely wrought, and ornamented with carvings from mantel to ceiling. The outhouses were spacious, and the grounds around the mansion, so late as 1860, occupied an entire square within the city. Its site was well chosen, for even now, surrounded as it is by the city, it commands a most remarkable prospect of the Hudson and the adjacent country. Below it are the slopes and plain toward the river, which once composed the magnificent lawn in front of the general's mansion; further on is a dense portion of the city; but looking over all the mass of buildings and shipping, the eyes take in much of the fine county of Rensselaer, on the opposite side of the river, and a view of the Hudson and its valley many miles southward.

In that mansion General Schuyler and his family dispensed a princely hospitality for almost forty years. Every stranger of distinction passing between New York and Canada, public functionaries of the province and state visiting Albany, and resident friends and relatives, always found a hearty welcome to bed and board under its roof. And when the British army had surrendered to the victorious republicans at Saratoga, in the autumn of 1777, Sir John Burgoyne, the accomplished commander of the royal troops, and many of his fellow-captives, were treated as friendly guests at the general's table. To this circumstance we have already alluded.

"We

were received by the good General Schuyler, his wife and daughters,"

says the Baroness Reidesel, "not as enemies, but as kind friends; and

they treated us with the most marked attention and politeness, as they did

General Burgoyne, who had caused General Schuyler's beautifully-finished house

to be burned. In fact, they behaved like persons of exalted minds, who determined

to bury all recollections of their own injuries in the contemplation of our

misfortunes. General Burgoyne was struck with General Schuyler's generosity,

and said to him, 'You show me great kindness, though I have done you much

injury.' 'That was the fate of war,' replied the brave man, 'let us say no

more about it.'"

"We

were received by the good General Schuyler, his wife and daughters,"

says the Baroness Reidesel, "not as enemies, but as kind friends; and

they treated us with the most marked attention and politeness, as they did

General Burgoyne, who had caused General Schuyler's beautifully-finished house

to be burned. In fact, they behaved like persons of exalted minds, who determined

to bury all recollections of their own injuries in the contemplation of our

misfortunes. General Burgoyne was struck with General Schuyler's generosity,

and said to him, 'You show me great kindness, though I have done you much

injury.' 'That was the fate of war,' replied the brave man, 'let us say no

more about it.'"

"The British commander was well received by Mrs. Schuyler," says the Marquis De Chastellux, in his "Travels in America," "and lodged in the best apartment in the house. An excellent supper was served him in the evening, the honours of which were done with so much grace that he was affected even to tears, and said, with a deep sigh, 'Indeed, this is doing too much for the man who has ravaged their lands and burned their dwellings.' The next morning he was reminded of his misfortunes by an incident that would have amused any one else. His bed was prepared in a large room, but as he had a numerous suite, or family, several mattresses were spread on the floor, for some officers to sleep near him. Schuyler's second son, a little fellow, about seven years old, very arch and forward, but very amiable, was running all the morning about the house. Opening the door of the saloon, he burst out a laughing on seeing all the English collected, and shut it after him, exclaiming, 'You are all my prisoners!' This innocent cruelty rendered them more melancholy than before."

Schuyler's mansion was the theatre of a stirring event, in

the summer of 1781. The general was then engaged  in

the civil service of his country, and was at home. The war was at its height,

and the person of Schuyler was regarded as a capital prize by his Tory enemies.

A plan was conceived to seize him, and carry him a prisoner into Canada. A

Tory of his neighbourhood, named Waltemeyer, a colleague of the more notorious

Joe Bettys, was employed for the purpose. With a party of his associates,

some Canadians and Indians, he prowled in the woods, near Albany, for several

days, awaiting a favourable opportunity. From a Dutch labourer, whom he seized,

he learned that the general was at home, and kept a body-guard of six men

in the house, three of them, in succession, being continually on duty. The

Dutchman was compelled to take an oath of secrecy, but appears to have made

a mental reservation, for, as soon as possible, he hastened to Schuyler's

house, and warned him of his peril.

in

the civil service of his country, and was at home. The war was at its height,

and the person of Schuyler was regarded as a capital prize by his Tory enemies.

A plan was conceived to seize him, and carry him a prisoner into Canada. A

Tory of his neighbourhood, named Waltemeyer, a colleague of the more notorious

Joe Bettys, was employed for the purpose. With a party of his associates,

some Canadians and Indians, he prowled in the woods, near Albany, for several

days, awaiting a favourable opportunity. From a Dutch labourer, whom he seized,

he learned that the general was at home, and kept a body-guard of six men

in the house, three of them, in succession, being continually on duty. The

Dutchman was compelled to take an oath of secrecy, but appears to have made

a mental reservation, for, as soon as possible, he hastened to Schuyler's

house, and warned him of his peril.

At the close of a sultry day in August, the general and his family were sitting in the large hall of the mansion; the servants were dispersed about the premises; three of the guard were asleep in the basement, and the other three were lying upon the grass in front of the house. The night had fallen, when a servant announced that a stranger at the back gate wished to speak with the general. His errand was immediately apprehended. The doors and windows were closed and barred, the family were hastily collected in an upper room, and the general ran to his bedchamber for his arms. From the window he saw the house surrounded by armed men. For the purpose of arousing the sentinels upon the grass, and, perhaps, alarm the town, then half a mile distant, he fired a pistol from the window. At that moment the assailants burst open the doors, and, at the same time, Mrs. Schuyler perceived that, in the confusion and alarm, in their retreat from the hall, her infant child, a few months old, had been left in a cradle in the nursery below. She was flying to the rescue of her child, when the general interposed, and prevented her. But her third daughter (who afterwards became the wife of the last Patroon of Rensselaerwyck) instantly rushed down stairs, snatched the still sleeping infant from the cradle, and bore it off in safety. One of the Indians hurled a sharp tomahawk at her as she ascended the stairs. It cut her dress within a few inches of the infant's head, and struck the stair rail at the lower turn, where the scar may be still seen. At that moment, Waltemeyer, supposing her to be a servant, exclaimed, "Wench, wench, where is your master?" With great presence of mind, she replied, "Gone to alarm the town." The general heard her, and, throwing up the window, called out, as if to a multitude, "Come on, my brave fellows! surround the house, and secure the villains!" The marauders were then in the dining-room, plundering the general's plate. With this, and the three guards that were in the house, and were disarmed, they made a precipitate retreat in the direction of Canada.

The infant daughter, who so narrowly escaped death, was the late Mrs. Catherine Van Rensselaer Cochran, of Oswego, New York, who was General Schuyler's youngest and last surviving child. She died toward the close of August, 1857, at the age of seventy-six years.

Albany was made the political metropolis of the State of New York early in the present century, when the Capitol, or State-House, was erected. It stands upon a hill at the heat of broad, steep, busy State Street, one hundred and thirty feet above the Hudson, and commands a fine prospect of the whole surrounding country, especially the rich agricultural district on the east side of the river. In front of the Capitol is a small well-shaded park, or enclosed public square, on the eastern side of which are costly white marble buildings devoted to the official business of the State and city. The Capitol is an unpretending structure, of brown free-stone from the Nyack quarries, below the Highlands. It is two stories in height, and ornamented with a portico, whose roof is supported by four grey marble columns of the Ionic order, tetrastyle. The building is surmounted by a dome supported by several small Ionic columns, and bearing upon its crown a wooden statue of Themis, the goddess of justice and law. Within it are halls for the two branches of the State legislature (Senate and General Assembly), an executive chamber for the official use of the Governor, an apartment for the Adjutant-General, and rooms for the use of the higher state courts.

Immediately in the rear of the Capitol is the building containing the State library, which includes nearly forty thousand volumes, and some valuable manuscripts. It is a free, but not a circulating, library.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.