Three Rivers

Hudson~Mohawk~Schoharie

History From America's Most Famous Valleys

Philip Schuyler and the Growth of New York, 1733-1804

Chapter Nine, Schuyler the Man

Philip Schuyler's story would not be complete without viewing him from three other vantage points: his business affairs, family relations, and elder statesmanship.

Business Affairs

Schuyler's political career coincided with other activities, including the managing of his own estate and the property of others. His responsibilities spread from lands at Saratoga and in the Mohawk Valley to Claverack, lower on the Hudson; they reached north along much of the St. Lawrence Valley. He administered the Claverack property that Mrs. Schuyler had inherited from her father, in addition to the business affairs of his son-in-law, Stephen Van Rensselaer. His executorship of John Bradstreet's estate extended from 1774 to 1794. As a member of the Board of Regents of The University of the State of New York he likewise was concerned with land matters, leases, and management. As head of the Northern and Western Inland Lock and Navigation Companies he was interested in improving land values, trade, and transportation.

The war years hampered Schuyler's development of the Saratoga estate, and British incursions from Canada sometimes caused tenants to leave the farms. Schuyler often remained at Saratoga to assist the military forces and to encourage his neighbors and tenants to stand firm. This was especially important in the years after Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga in 1777.

As of December 1778, Schuyler estimated that the war so far had cost him 20,000 pounds (specie) through property losses, and the use of. his personal credit for the cause, and depreciation of currency. Much of the produce of his farms and mills was channeled into the military effort, but much of it was also destroyed. John Schuyler greatly assisted his father in managing the property until he died in 1795. Thereafter the General again faced heavy duties of supervising the estate, which by 1803 included many buildings and several mills.

Schuyler's purchase of about eight thousand acres of Cosby's Manor in the Mohawk Valley in 1772 proved to be no exception to the long, involved difficulties of landlords and speculators. He had to pay quitrents on the property to the State after the royal government ceased, and not until 1793 did he settle the error in the original sale from the manor heirs.

The settlement of John Bradstreet's share in the purchase was also a trial. As executor of the estate after Bradstreet's death in 1774, he faced a hard job in disposing of it and conveying funds to the impatient heirs in England. In 1788 Schuyler had to answer a formal complaint in the State chancery court by Bradstreet's daughter, Agatha Evans, who charged that he had mismanaged the inheritance. He finally conveyed the lands to Mrs. Evans in 1794. He had also benefited from Bradstreet's patronage and largesse: Bradstreet's will cancelled a large debt Schuyler owed, and provided various bequests to Mrs. Schuyler and her children.

No less a trial than the Bradstreet estate was Mrs. Schuyler's share in the Claverack and Hillsdale property of her father. Here a tedious boundary dispute with the Livingstons, who owned the neighboring manor, dragged on for years. Mrs. Schuyler's brothers demanded a partition of the property and the tenants in the area had proved contentious. Schuyler dealt with his brothers-in-law by directing a survey in 1784. Six years later the tenants prompted him to prepare an address on the subject of their rents which were in arrears. He called for adjustments in the rent conditions on an "honest man's principles," without recourse to the courts. If the tenants did not accept what he thought were generous terms, Schuyler vowed to pursue every measure countenanced by the law to recover the property. He thus revealed his personality as a landlord and as a guardian of his wife's interests. The General's arrangements evidently did not end all these difficulties; in 1794, for example, he invoked the law in the circuit court for Columbia County to evict a number of tenants and to sell about twelve hundred acres of their farms.

Schuyler's landholdings were enormous and far flung by both current and 18th century standards. Total acreage figures for his real estate are impossible to reckon exactly, but clues to the extent of his property at various times exist. His prewar acquisitions have been noted, but they seem modest in comparison to his later accumulations. His quitrent payments to the State treasurer in the 1780's indicate that he owned several parcels in the Mohawk Valley, each varying in size from 1,300 to 5,500 acres-a total of at least 17,800. In 1787 he and about a dozen other speculators (including Stephen Van Rensselaer, Gouverneur Morris, Henry Knox, and Alexander Hamilton) purchased a half million acres along the St. Lawrence River. By June 1791 Schuyler had sold his share in the tract, known as the Ten Townships, which he calculated at over 45,000 acres. These are but two examples of his possessions.

Schuyler's wealth, of course, ranked him with men of power and influence, but by the time of his death he was richer in real property than in other assets. According to an 1805 appraisal of his estate, these included: arrears in tenants' rents, $3,858.36; plate and household goods, $4,735.54; ten shares in the Bank of Albany, $4,000; debts supposed to be "good," (15,666.54, and those reckoned as "bad," $2,958.63. His will indicated no property in slaves, though Schuyler did own a number of them for most of his life. Accounts among his papers reveal that in 1776 he had at least nine. The 1790 census indicates the General had 13 slaves in Albany, and his son had 14 others at Saratoga. In 1800 Schuyler owned at least 11 slaves, but by the time he died, he must have disposed of them by conveyance or manumission.

Schuyler's business affairs included promotion of internal improvements for New York, an activity shaped both by a desire for gain and a wish to see the State and nation enjoy a flourishing economy. The General thus bent his energies to incorporate the Northern and Western Inland Lock and Navigation Companies in 1792. Thereafter, until 1804, he led their projects with unflagging interest. The results of his labors are suggested by the 1805 inventory of his estate: 5 shares in the Northern Company were worthless; 10 shares in the Western Company, originally costing $2,500, were valued at $2,000.

These companies provided the trial and error spade work on which Yorkers drew for their monumental effort of building the Erie Canal. Benson J. Lossing styled Schuyler the father of the New York canal system - an apt title although many other men had a part in the business. The General displayed vision in the undertaking, and he matched it with energies of body and will. The concept of inland lock and navigation improvement was by no means original with Philip Schuyler. The prospects had been considered as early as 1724 when Surveyor General Cadwallader Colden had given official attention to them. The efforts of Christopher Colles and Elkanah Watson immediately preceded Schuyler's involvement in the matter.

Many difficulties faced Schuyler in managing the canal companies. Aside from hiring workers, provisioning and housing them, supervising the overseers and reviewing accounts, not to mention recurrent appeals to the legislature for aid and to the public for subscriptions of stock, Schuyler was weighted with the responsibilities of finding durable building materials for the locks, some of which were constructed successively of wood, brick, and stone. Also, political enemies like De Witt Clinton charged Schuyler with failing to obtain a qualified engineer to direct the works and with the audacity to attempt supervision himself.

Schuyler was the master spirit who infused life and vigor into executing the canal enterprise. His accomplishments in practical terms were perhaps less significant than the impetus he gave to an idea. Yet by 1796, a 4,752 foot canal with five locks had been dug around Little Falls in the Mohawk Valley. The following year a two-mile canal system at Fort Stanwix made possible the passage of boats from the Mohawk to Wood Creek. The link at Fort Stanwix reduced the time for passing a boat from a day to an hour. In 1798 Wood Creek was cleared of fallen timber, its course shortened, and another one and one-quarter mile canal with two locks at Wolf Rift was constructed in the German Flatts area. These improvements allowed 60-foot long boats carrying 16-ton cargoes to replace smaller, l 1/2-ton boats. The cost of freighting from Albany to Seneca Lake was cut from $100 per ton to $32.

The Northern Company accomplished little in comparison to the Western Company, and it too was a costly undertaking. High tolls slowed the development of the two companies, but the tolls increased year by year as commerce along the Mohawk flourished even though the Western Company paid only one dividend (three percent) in Schuyler's lifetime. By 1803 the company's revenues amounted to about $10,000, compared to expenditures of more than $400,000. The enterprise was such that only long-range operation could compensate for the heavy initial capital outlay. The company's accounts were not closed until 1820 when the State bought its property for the Erie Canal project. However mixed the success and failures of Schuyler's labor, one point is clear: the prospects were fair enough that other men shared his vision, and 20 years after the General's death, they helped make possible the Erie and Champlain Canals.

Family Relations

Invariably Philip Schuyler has been portrayed as austerely aristocratic, proud, unbending, and more than a little stuffy, so much so that he hardly seems human. Of course these traits were parts of his character, but they certainly do not account for the whole man. According to the reminiscences of his daughter, Catherine Van Rensselaer Schuyler, the General was an early riser who believed seven hours of sleep were adequate for any healthy man when duty called. His day began with private devotions and a stint at study, fiscal calculations, or surveying problems. While health permitted, he read prayers to his household, and after breakfast dealt with correspondence. Before noon he often rode to Lewis's Tavern in Albany to enjoy the conviviality of men like Chancellor James Kent, Abraham Van Vechten, and John V. Henry, other gentlemen of the law. Schuyler was a fastidious man, a trait that accords with his reputation for austerity and proud bearing, and he insisted that his children follow his example in dress so as never to be "disturbed" by unexpected guests. His daughter was impressed by Schuyler's high mindedness: "He abhorred scandal: checked everything like it; and was the most forgiving of men. He said that no one truly forgave a wrong who liked to recall it."

Schuyler's' personality and character shine through the record of his family relations, perhaps nowhere more revealingly than in his ties with his son-in-law and daughter, Alexander and Elizabeth (or Eliza) Hamilton. Eliza probably met Hamilton at Washington's Morristown headquarters in the winter of 1779-1780 when her father was visiting the commander-in-chief on congressional business. In March 1780 they were engaged after carefully procuring the Schuylers' consent. (There was to be no repetition of Angelica Schuyler's 1777 elopement with John Barker Church to sadden or anger her father and mother.) After Eliza was married in December 1780 in her parents' drawing-room, Hamilton and Schuyler developed a camaraderie that grew with every passing year. They were kindred spirits, men of similar principles, predilections and visions. After the Revolutionary War the two men nurtured their mutual aims and principles, worked to strengthen the Confederation, and then labored to replace it with a new Constitution. In everything, Schuyler offered his assistance; as in plans for national fiscal policy, so in the Hamiltons' building of a house.

Those who knew him intimately regularly attested to Schuyler's hospitality and conviviality, even though the public's picture of him was that of the aloof, haughty dogmatist, jealous of his honor, insistent upon his prerogatives, sharp in partisanship and wise, if overbearing, in statesmanship. The holiday season of 1780-1781 is one of the best examples of Schuyler's congeniality. Shortly after his daughter married Hamilton in December 1780, several French officers arrived in Albany. Led by the Chevalier (later the Marquis) de Chastellux, these men were brought to Schuyler's door in his own "sledge." Chastellux was delighted by the General's openhanded reception and fine Madeira, and particularly noticed his lovely daughters and impressive wife. Evidently the Chevalier found Mrs. Schuyler a bit formidable, for he noted the "rather serious disposition" of this "big Dutchwoman" who "appeared to be the mistress of the house. . . ." During one evening's visit she showed no inclination to play hostess, and Schuyler entertained Chastellux alone.

Only 8 of Schuyler's 15 children survived childbirth or infancy. Those who did enjoyed their father's affection and patriarchal concern, as his letters indicate. He delighted in the company of his grandchildren. An example of Schuyler's parental direction is a letter to his youngest daughter Catherine in December 1799. He advised the 18-year-old girl to read Addison's works as they "tend to inculcate virtue in every shape. . . ." "Take every opportunity of conversing in French," he further admonished. "Your sister [Angelica] Church and your nieces speak it well and I instruct you to use that language in all your intercourse with them, when persons are not present who do not understand it."

One of Schuyler's last letters to Eliza Hamilton sums up his tender regard for all of his family. Taken in the context of his declining years, the death of his grandson Philip Hamilton in a duel in 1801, Mrs. Schuyler's death in March 1803 and Hamilton's passing in July 1804, it is a touching missive. "My dearly beloved child," he wrote, "how greatly do your affectionate Attentions, and those of my other children, sooth [e] & comfort me, and how sincerely do I reciprocate those affections." Solicitous for Eliza's and her children's welfare, he urged her to make her wants known so he might relieve them; Schuyler invoked divine protection for his family that "every thorn" might be plucked from their "future path."

It was almost fortuitous that Schuyler and Hamilton should both have died in 1804: Hamilton from Burr's bullet, Schuyler from age, illness, and perhaps despondency. Their influence and activity had slumped as their political opponents' increased. Schuyler was part of the animus which led to the Burr-Hamilton duel, for Burr had been his political rival. It was Burr who had replaced Schuyler as United States Senator in 1791, and had swung New York City and County into the Republican camp in 1800, thus wresting control of the state legislature from the Federalists and enabling it to choose presidential electors pledged to Jefferson and Burr.

Elder Statesman

A measure of Schuyler the man may be taken from his record as elder statesman as well as from his business affairs and family relations. His concept of the duty of public service could not but lead him into many endeavors, and as his reputation for it grew, he was drawn into varied public tasks. Thus, at his death, the Albany Gazette could report that Schuyler's involvements had impressed "his agency and character" on public affairs for many years, and the social system had "felt the influence of his genius and his labors. . . ." His major roles have been sketched; what were the lesser ones as an elder statesman? He was a member of the Society of the Cincinnati, the New York State Board of Regents, a commission for prison construction and the Society for the Promotion of Agriculture, Arts, and Manufactures. Most of these roles reveal Schuyler's commitment to 18th-century Enlightenment principles: the diffusion of useful knowledge, humanitarian reform, and the importance of experimental empiricism-all characteristic of his own activities.

In 1804 the Albany Gazette eulogized Schuyler's interest in schools and education as well as his patriotism. "Without the distinction of an early education strictly classical," it said, "he was yet as extensively acquainted with books as with men:" Indeed, Schuyler's library suggested as much, and his daughter Catherine has reported that the General began to study German in order to read books on surveying after he recovered from an eye malady in 1797-1798. This private interest in learning carried over into public life; in 1779, for example, Schuyler joined a group of petitioners to ask the legislature to incorporate a college at Schenectady.

After the legislature established a state university system headed by a Board of Regents in 1784, Schuyler was elected a Regent (1787) and remained one for the rest of his life. From this position he was able to assist the Reverend Dirck Romeyn in establishing Union College at Schenectady in 1795. Schuyler supported Romeyn's school with personal gifts, and in 1795 he proposed that the legislature grant £ 1,500 for books and apparatus for lectures in astronomy, geography, and natural philosophy. Other work on the Board of Regents involved Schuyler in the leasing and management of lands devoted to the support of education. This was a significant part of the Board's responsibilities, for it not only had authority to incorporate and supervise new colleges and academies but also the limited public resources to subsidize them.

Schuyler also demonstrated interest in Enlightenment principles through humanitarian endeavors. He developed this concern along with the Quaker merchant, Thomas Eddy, who was Schuyler's associate in the Western Inland Lock and Navigation Company. Taking their lead from Pennsylvania Quakers' work for penal law and prison reforms. Eddy and Schuyler studied Philadelphia's Walnut Street jail and Pennsylvania's penal code. The result was a reduction in 1796 by the New York Legislature of the state's 16 capital offenses to murder and treason, substitution of imprisonment for corporal punishment in noncapital crimes, and a provision for two new state penitentiaries, at New York and Albany. Schuyler was named to the commission for erecting the Albany prison, while Eddy directed the New York project. The Albany commissioners proceeded to purchase land for the building, but within a year the project was abandoned because of the small number of prisoners from upstate New York. By then Schuyler's connection with Eddy had helped another humanitarian project: as State senator in 1795 Schuyler had introduced a bill for the New York City hospital, and $40,000 was voted for a four-year period. The grant was subsequently enlarged and extended.

Another aspect of Schuyler's reflection of the Enlightenment of his age was his interest in agriculture. His familiarity with the science of cultivation and his knowledge of nature were cited by his 1804 eulogist, corroborated by his account books and letters, and proved by his long seasons in the country, his development of a flax mill in 1767 (for which he was awarded a medal by the provincial Society for Promoting the Arts, Agriculture, and Economy) and by his membership in the "Society Instituted in the State of New York, for the Promotion of Agriculture, Arts, and Manufactures." Sometime after 1799 he published in the society's "Transactions" "An Essay, Suggesting a Plan to Introduce Uniformity in the Weights and Measures of the United States of America." Schuyler's other scientific interests included his search in 1790 for a "very fine boar" and two "large and fine" sows as breeding stock, and an acquaintanceship with David Rittenhouse when the latter produced an instrument for taking water levels for the inland lock and navigation enterprise.

Thus the role of elder statesman did not mean seclusion for Schuyler until about the year of his death. Private interest and public duty were so much a part of his character that only illness could interrupt and finally halt his work as patriot, humanitarian, canal promoter, and student of science.

An Estimate

On the evening of Sunday, November 18, 1804, Philip Schuyler was gathered to his fathers. What mark had he made in the world: on his country, as a subject of the British Crown, as a citizen of the United States ? What is his place in the history of New York and of the nation ? (Schuyler was perhaps not the greatest of men but neither was he among the smallest.) The decisions he made and his influence on his world have been suggested above. His biography, like all biographies, reveals complexity of motive, and his life shows that he was moved by a combination of self-interest, noble principles, and practical vision. Perhaps the words of his obituary writer and of his eulogist are as fair an assessment of him as any other. Perhaps his contemporaries knew him better than can we with all our advantages of hindsight and perspective.

On November 19, 1804, Schuyler's death notice in the Albany Gazette included a tribute to his useful labors in both military and civil affairs and to his sound moral and political principles. His statesmanship was practical, not theoretical, and his projects were utilitarian. No believer in the perfectibility of man, Schuyler based his principles of politics on the experience of the ages, and believed that popular liberties could be preserved only "by the wholesome restraints of a Constitution and laws, energetic, yet free." A man whose dignity was tempered by courtesy and hospitality, Schuyler was endeared to those who knew his "pleasing and instructive" companionship, ardent friendship and just dealings.

A week later the Gazette printed a eulogy. Schuyler's death was said to have left a "sensation of vacuity never to be supplied," for in the past 30 years, there had been little public business in which he had not taken some part, or "contributed some aid or influence. . . . His temper was ardent . . . but if ever urged too far by the heat of the moment, his kindness was sure to return, and with it, generosity resumed its habitual sway." Impatient with impertinence, absurdity, and folly, Schuyler revealed his principles in the movement of his passions. If he was a "friend to strict political discipline," a partisan, it was because he believed it to be "the best preservative of liberty," and as he was "too proudly honest to be indiscriminately popular, and holding in utter abhorence the intrigues of demagoguy and the spirit of mob-government, he found many among the interested, the ambitious, the envious and factious, who ventured to question his patriotism. . . ." Drawing "a full and complete portrait of this eminent man," the newspaper warned, was an arduous task. Indeed it has never been done, and Schuyler has neither been widely known nor correctly and completely recognized for the place he occupied in the early history of the nation. Perhaps that place will never be apprehended, for "Even in history, something will be lost or defective-because genius . . . often pervades a system unseen . . . communicates an influence that cannot be traced."

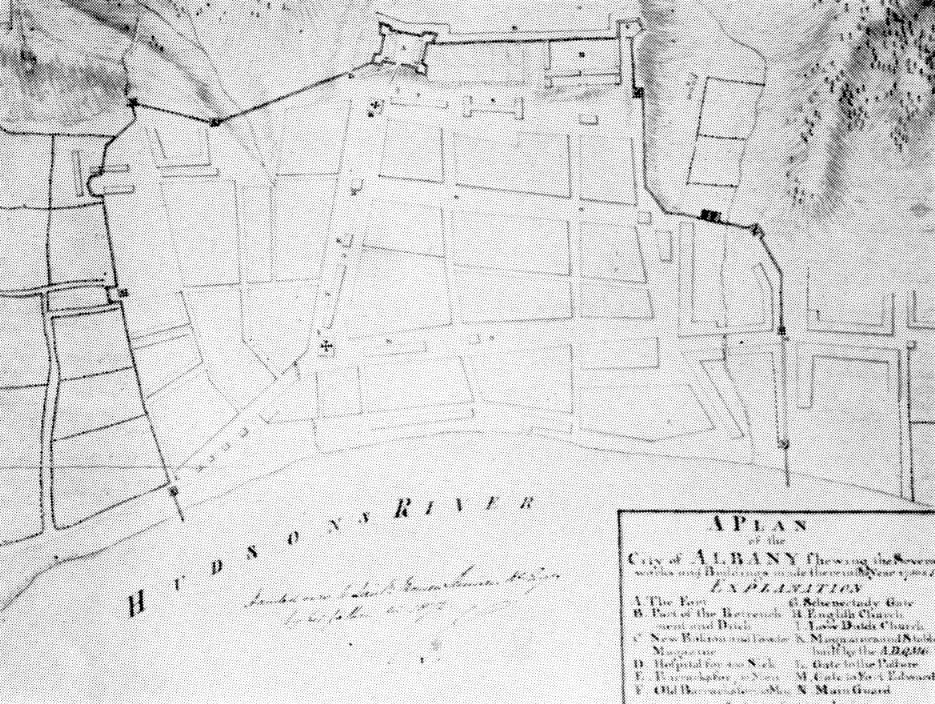

PLAN OF THE CITY OF ALBANY 1756-57

Original in the British Museum

Copyright © 1998, -- 2003. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.